You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Inappropriate social media posts from current and soon-to-be college students have made news headlines lately. Students, however, aren’t the only ones who need to hone their digital literacy skills. Many professors also need to think twice about their digital discourse.

Student offenses online have dominated discussions in the media. Ten prospective Harvard College students recently had their admissions offers rescinded for racist, violent and/or explicit posts in a private Facebook group chat. Texas State University is currently investigating a student leader for tweets depicting a black male student being lynched and homophobic private messages sent to the same student. At Belmont University, the largest Christian university in Tennessee, a student was expelled after using a racial slur to refer to protesting NFL players on Snapchat and saying they needed “a damn bullet in their head.”

Colleges have made it clear that they will not tolerate student behavior antithetical to their values, even in the off-campus, online sphere of social media. When students have challenged expulsions for social media posts through lawsuits, courts have sided with colleges. It seems that some students are struggling to participate in digital discourse on social media without jeopardizing their college careers.

Numerous commentators have offered words of wisdom to these members of Generation Z. One especially insightful New York Times article by author and digital media expert Luvvie Ajayi implores those of us who remember a time before the internet’s ubiquity to teach students about digital literacy -- defined by the American Library Association as “the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills.”

Among Ajayi’s suggestions are that we teach students that: 1) even private online correspondence is permanent and 2) while they do not have to present overly sanitized versions of themselves online, they should not post anything that they would not want to see on a Times Square billboard. I completely agree with Ajayi’s sentiment and suggestions. A student’s digital reputation can be just as important as academic accomplishments, extracurricular activities and interview skills when applying for everything from college to scholarships to jobs.

Online issues, however, go beyond students alone. Today’s professors, including myself, are using the internet to connect with and engage both students and others. In some of my classes, Facebook and Twitter are integrated into the syllabus. In other classes, I encourage my students to blog about topics of interest, sometimes for a grade. In limited circumstances, I will text students about academic or other matters.

But when I receive a notice that a student has followed me on Twitter, requested to connect on LinkedIn or sent me a friend request on Facebook, I seriously consider how that engagement might influence my online activities. In addition, I do a fair amount of public writing and communication online. With each post and publication, I think about how it may impact my digital reputation and institutional capital. This is, in part, because I’ve seen what has happened with other colleagues in the academy.

Several professors have found themselves in hot water over both online comments made on both personal and professional bases. Among recent examples, the recent public disagreement between a professor and a student at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville stands out as the poster child for professorial digital literacy.

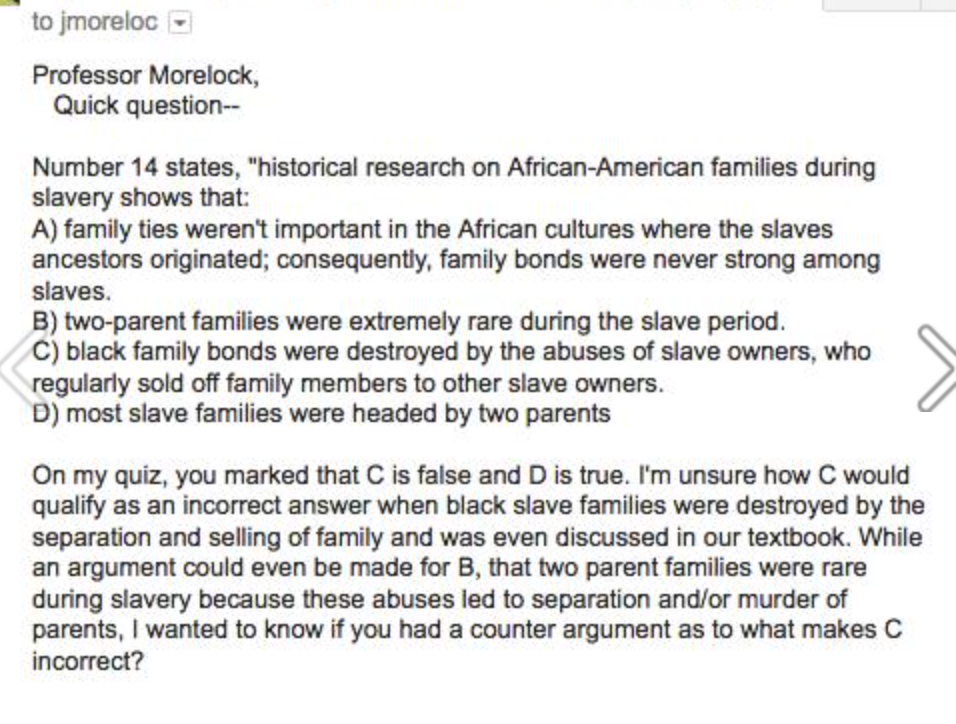

The dispute between Kayla Renee Parker, a senior, and Judy Morelock, a 30-year lecturer at the university, began with the following email about a quiz question.

This led to significant back-and-forth between Parker and Morelock, much of which was memorialized online. Morelock apparently began commenting on Parker’s Facebook page about the dispute -- at least until Parker blocked her. Thereafter, Morelock posted messages on her own Facebook page widely believed to be about Parker, though Morelock disputes that all of the posts were directed at the student.

Morelock’s posts included the following, which seemed to suggest that she would retaliate against the student in the future: “After the semester is over, and she is no longer my student, I will post her name, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn … After she graduates and I retire, all bets are off,” “Ignore the facts, promote a misinformed viewpoint, trash me and I will fight you,” “Once you spread venomous rumors and try to destroy a person’s reputation, you cannot undo the damage. You also will not be forgotten or forgiven #karmawillfindyou,” and “She’s on LinkedIn trying to establish professional contacts. This will be fun!” Morelock’s final post, which Parker says was also directed at her, included a graphic sexual reference and an expletive.

Parker subsequently showed the posts to the university’s administration and then wrote an blog post titled “Beware of Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing: The Tale of a Progressive Professor Who Forgot to Hide Her Racism and Got Her Ass Fired.” As the title indicates, Morelock’s career at Knoxville ended after this episode, although the university would not confirm the reason for this development.

This debacle has raised numerous concerns in academic circles. Chief among them relate to both academic freedom and the First Amendment right to free speech. While universities by and large tout a commitment to both principles, professors at both public and private institutions can quickly find themselves embroiled in investigations, facing disciplinary proceedings and/or placed on academic leave because of their online communications.

Regardless of one’s beliefs about whether a professor’s social media posts should be protected speech, the reality is that such comments could negatively impact a professor’s career and even lead to firing. Private colleges and universities are not bound by the First Amendment and, as such, do not have to recognize a professor’s right to free speech. While public institutions are bound by the First Amendment, the law does allow employers to discipline employees for speech under some circumstances. In addition, the notion of academic freedom is not coextensive with legal rights and may be more dependent on an institution’s internal policies and contractual obligations than legal rights.

For those reasons, digital literacy is critically important to professors engaging in online activities, especially through social media. Here are ways professors can ensure their own digital literacy.

- Know your institution’s or board’s policies on social media and academic freedom. This document should outline what is and is not permissible for the institution’s faculty and how academic freedom is defined. Note that your position at a public university or as a tenured professor may not insulate you from discipline. The Kansas Board of Regents’ social media policy, for example, allows any faculty member to be fired for “improper use of social media.”

- Understand privacy settings for your social media accounts and use them. This suggestion, of course, is not foolproof. As Ajayi explains, “privacy ain’t privacy anymore.” Someone may take a screenshot of your posts and preserve them elsewhere for digital eternity.

- Develop strategies for connecting and interacting with students. Having social media friends and followers who also currently sit in your classroom may require an additional level of consideration when posting online. Some social media services allow users to group certain friends or followers into categories with limited access to posts. Some have even suggested that professors keep their social media spaces off-limits to students.

- Above all, remain true to yourself (also a suggestion from Ajayi). Academic freedom is, of course, essential to much of a professor’s work. Social media accounts often embody important communications connecting the academy to the public, and that should not change. Choosing digital boundaries is a personal decision largely dependent on an individual’s level of comfort with their tweets and posts appearing on the proverbial Times Square billboard.

This writing is not mean to suggest that professors should self-censor any potentially salacious social media posts. It is, however, designed to provide professors with context and strategies for cultivating digital reputations that preserve both their professional integrity and academic careers. Digital literacy is important for faculty members, too.