You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

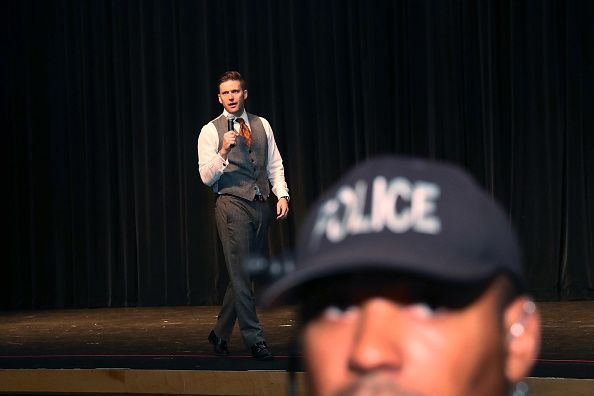

Richard Spencer at the University of Florida

Getty Images

President Trump is focusing on the wrong problem. He announced Saturday that he is planning to issue an executive order that would punish colleges and universities that “do not support free speech” by denying them federal research funds. In a speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference, Trump said, “If they [institutions of higher education] want our dollars and we give them by the billions, they’ve got to allow people to speak.”

This was prompted by an incident where a man (who is not a student) was on the University of California, Berkeley’s campus praising Trump and another man (also not a student at Berkeley) punched him.

Unfortunately, Trump’s response is wrongheaded. Like many others, the president mistakenly criticizes colleges and universities for not protecting free speech, when in fact, institutions of higher education have demonstrated repeatedly that they are staunch supporters of the First Amendment, as well as of related core values such as academic freedom and the pursuit of knowledge and truth. Colleges and universities actually are crucial allies in the promotion and protection of not only free speech, but also the open exchange of ideas and dialogue across difference.

The mistake that Trump and others make is to assume that to protect freedom of speech, campus leaders and faculty have to allow people on campus to say whatever they want. Valuing free speech does not have to come at the expense of students’ and faculty’s pursuit of knowledge and truth, a (some might say the) fundamental mission of higher education. Campus leaders can lean on their campus’s mission and on academic freedom to champion both truth and free speech on campus.

Mission

Because almost across the board institutional missions center on scientific discovery, knowledge and learning, institutions of higher education are a key mechanism for fostering democratic education. Campuses often subscribe to John Stuart Mill’s notion that a university is a “marketplace of ideas,” where educators offer “balanced perspectives” so that students can “hear the other side” on every issue.

However, academic freedom guidelines specifically say that faculty members need not always cover “the other side” if the standards of the discipline deem that other side to be untrue. When topics seem to be settled, with a right answer having emerged through science and ethics, faculty can focus on the knowledge produced. A white nationalist view, for example, does not merit debate within the campus marketplace of ideas.

In the aftermath of the Charlottesville, Va., tragedy, these disagreements have taken on a deeper significance, as those of us who work within higher education navigate increasingly polarized contexts for teaching, learning and research. Public discussions of these issues have been dominated by legal analyses of the First Amendment, without sufficient attention to philosophical discussion of disagreement, truth and the democratic purposes of higher education.

College faculty and campus leaders are caught between wanting to be nonpartisan and promoting their institution’s missions, which often prioritize excellence and truth. An example of this comes from my own public university. Our guiding principles include commitments to “Maintain a commitment to excellence,” “Promote and uphold principles of ethics, integrity, transparency and accountability,” “Encourage, honor and respect teaching, learning and academic culture,” and “Promote faculty, student and staff diversity to ensure the rich interchange of ideas in the pursuit of truth and learning, including diversity of political, geographic, cultural, intellectual and philosophical perspectives.” Key parts of the institution’s mission -- “excellence,” “teaching, learning and academic culture,” and “the pursuit of truth and learning” -- require us to uphold both freedom of speech and the truth.

Academic Freedom

In the debates over speech on campus, freedom of speech has taken center stage, but it is actually academic freedom that should provide the guidelines campuses need in evaluating questionable claims of free speech. While free speech is protected by the First Amendment, academic freedom is not a legal right. It is more specialized and contextual because it is protected within the university, a place where we pursue discovery, knowledge and truth, and where we teach.

A key difference between academic freedom and general freedom of speech is truth, and the disciplinary norms for scholarship. In addition to protecting teachers and learners from political censorship, academic freedom gives faculty members the right to create knowledge and pursue truth in the context of the established standards and methods of their disciplines through which truth is established. As Peter Wood of the National Association of Scholars has written, “No rule or law says that a university must assist a faculty member in spreading falsehoods.” This is relevant for the formal classroom as well as other educational spaces on campus.

It is academic freedom that would allow campus leaders to bar certain speakers from campus. For example, David Irving has spoken on a number of campuses. Irving was and is notorious for being a racist, anti-Semitic person who denies that the Holocaust occurred -- an untenable, wrong view if ever there was one.

More recently, Richard Spencer spoke on some campuses, such as the University of Florida. Spencer has called for “ethnic cleansing” and he regularly incites intimidation and violence based racial, religious and ethnic animosity. Campus leaders certainly have scientific and ethical warrant to bar such speakers from campus, as they are espousing ideas that have been discredited unequivocally, that are false, which is different from merely offensive or unpopular views. Leaders can rely on the tenets of academic freedom and, from this understanding, would not violate the First Amendment when barring speakers espousing known lies.

The great American philosopher John Dewey was right that democracy has to be renewed with each generation. Yet Dewey did not adequately focus on how to do so when people have divergent views about democracy and the democratic purposes of public institutions. Relatedly, Elizabeth Anderson argues that democracy ought to be lived on college campuses: “The best model of relations,” she writes, “is a democratic one that enforces relations of equality among inquirers. This model imposes certain content and viewpoint constraints on expression in the academy, but in ways required by academic freedom itself.”

Because colleges and universities have social missions and serve our democratic society, they are far from spaces where anything goes. Consider that many public institutions of higher education restrict faculty from partisan political campaigning or trying to influence an election, things that are surely within a person’s rights in general.

So, are limits to the airing of certain ideas permissible at institutions of higher education? If so, under what circumstances and justifications? Understanding institutional missions and values, as well as the tenets of academic freedom, will help students, teachers and campus leaders make principled decisions in the context of what might be high-pressure, contentious circumstances.

Ultimately, campus leaders need to engage with diverse students and constituents who come to us with many different social and political values and beliefs. And they need to do so with integrity on increasingly fragmented college campuses, providing clear justifications of their ethical choices to champion the value of open exchange alongside the value of truth. We used to care about pursuing truth and protecting free speech on college campuses. Pursuing truth and knowledge were not seen as mutually exclusive from promoting the open exchange of ideas for which U.S. campuses are known.

My argument here is not about sacrificing freedom of speech in order merely to avoid offending someone or hurting someone’s feelings. This is not about hurt feelings -- it is about views that are indefensible by disciplinary, scientific and ethical standards. There is a profound cost to public universities when they succumb to political pressures to present "balanced" perspectives on anything and everything, even when certain perspectives are false or wrong. There are not two sides to every story when one of those sides is a lie.