You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Jen Kim/Inside Higher Ed

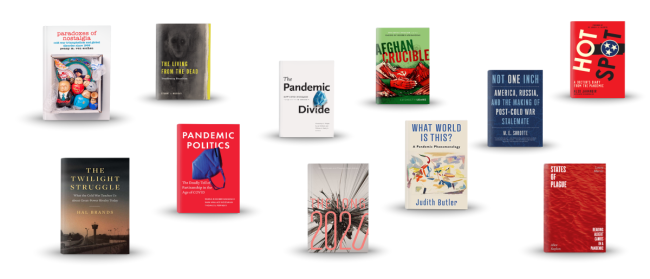

Looking over the university press titles coming in the fall, I find two distinctive clusters of books standing out as topical. In tune with recent news, they also bring up unfinished business from years past.

At present, only about half of the presses have made their catalogs available. The rest should arrive over the next month or so, allowing for a broader view of trends or themes. But for now, here’s the roundup as of Memorial Day weekend. (Quoted text below is taken from university press materials.)

Recent developments no doubt account for the speedy reissue, in less expensive editions, of two volumes Yale University Press published in hardcover just a few months ago. M. E. Sarotte’s Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post–Cold War Stalemate (appearing in hardcover last November, out in paperback in August) “pulls back the curtain on the crucial decade between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of Vladimir Putin,” when “the seeds of the tensions that shape today’s world” were sown in conflicts over NATO’s expansion and Europe’s geopolitical prospects. Hal Brands’s The Twilight Struggle: What the Cold War Teaches Us About Great‐Power Rivalry Today (hardcover released in January of this year, paperback slated for September) anticipates that “an era of long‐term great‐power competition with China and Russia” will require the United States to “look to the history of the Cold War for lessons on how to succeed in great‐power rivalry today.”

Given that Cold War tensions repeatedly escalated to a point just shy of thermonuclear warfare, I’m not at all sure that excelling in great-power rivalry is much better than demonstrating proficiency at Russian roulette. Penny M. Von Eschen’s Paradoxes of Nostalgia: Cold War Triumphalism and Global Disorder Since 1989 (Duke University Press, July) sounds skeptical about the rewards of “winning.” Drawing on “diplomatic archives, museums, films, and video games,” the author considers how “triumphalist claims that capitalism and military might won” the Cold War actually “distort the past and disfigure the present,” fueling “the ascendancy of xenophobic right-wing nationalism and the embrace of authoritarian sensibilities in the United States and beyond.”

Of course, “Russia” has become a byword for “xenophobic right-wing nationalism and the embrace of authoritarian sensibilities” as well, with its own culture of nostalgia. People can sentimentalize anything, but the history Elisabeth Leake treats in Afghan Crucible: The Soviet Invasion and the Making of Modern Afghanistan (Oxford University Press, June) seems resistant to misty watercolor memories. The Red Army invasion in 1979 was followed by almost a decade of “parallel covert American aid to Afghan resistance fighters,” contributing to “a moment of crisis not just for Afghanistan or the Cold War but international relations and the postcolonial state.”

The Soviet war in Afghanistan was a “defining event of international politics in the final years of the Cold War, lingering far beyond the Soviet Union’s own demise,” as Leake writes. Fortunately, one of the author’s major concerns is to ensure that the Afghans themselves do not disappear from the story.

The millionth person in the United States died of COVID-19 this month; the global toll has reached almost 6.3 million. Alex Jahangir’s Hot Spot: A Doctor’s Diary From the Pandemic (Vanderbilt University Press, September) takes readers back to disease’s arrival in Nashville, Tenn., in March 2020. The author, a trauma surgeon, “unexpectedly found himself head of the city’s Coronavirus Task Force and responsible for leading it through uncharted waters.” His “op notes (the journal-like entries surgeons often keep following operations) … expanded to include his personal reflections and a glimpse into the inner sanctums of city and state governance in crisis.”

Other expert reflections on that year are assembled by Richard Grusin and Maureen Ryan, the editors of The Long 2020 (University of Minnesota Press, January 2023). Essays by “a strikingly interdisciplinary group of scholars and thinkers” consider the “epidemiological, political, ecological, and social” crises of that year as the world “careened from one unfolding catastrophe to another.” (The book’s description left me with a vague sense that it was already in print. My mistake, to be sure, but also something other than bad déjà vu: earlier this year, Columbia University Press published The Long Year: A 2020 Reader, edited by Thomas J. Sugrue and Caitlin Zaloom, in which “some of the world’s most incisive thinkers excavate 2020’s buried crises, revealing how they must be confronted in order to achieve a more equal future.”)

Other forthcoming titles focus on how the pandemic worsened the country’s disparities and vice versa. Disproportionate rates of “illnesses, outbreaks, and deaths” among Black and Latinx populations are at the focus of The Pandemic Divide: How COVID Increased Inequality in America (Duke University Press, November), a collection of papers edited by Gwendolyn L. Wright, Lucas Hubbard and William A. Darity. Contributors assess “COVID-19’s impact on multiple arenas of daily life—including wealth, health, housing, employment, and education—while highlighting what steps could have been taken to mitigate the full force of the pandemic.”

Shana Kushner Gadarian, Sara Wallace Goodman and Thomas B. Pepinsky—the authors of Pandemic Politics: The Deadly Toll of Partisanship in the Age of COVID (Princeton University Press, October)—cite “a wealth of new data on public opinion” showing how, “when solidarity and bipartisan unity were sorely needed, Americans came to see the pandemic in partisan terms, adopting behaviors and attitudes that continue to divide us today.”

Judith Butler’s What World Is This? A Pandemic Phenomenology (Columbia University Press, November) finds COVID raising “fundamental questions about our place in the world: the many ways humans rely on one another, how we vitally and sometimes fatally breathe the same air, share the surfaces of the earth, and exist in proximity to other porous creatures in order to live in a social world.” Disaster on a global level exposes our commonalities and shared vulnerabilities, as well as the “forms of injustice that deny the essential interrelationship of living creatures.”

Another theoretical take on how society understands and responds to the pandemic is Stuart J. Murray’s The Living From the Dead: Disaffirming Biopolitics (Penn State University Press, September). Foucault’s concept of biopolitics subsumes a variety of institutions and practices seeking to monitor, structure and control human populations. The author interrogates “the concept of ‘sacrifice’ in the ‘war’ against COVID-19” and “legal cases involving ‘preventable’ and ‘untimely’ childhood deaths,” among other matters, asking, “How might we reckon with ethical responsibility when we are complicit in sacrificial economies that produce and tolerate death as a necessity of life?”

Finally, at the intersection of literature and everyday life: Albert Camus’s second novel, The Plague, first published in 1947, found a new readership during 2020. Alice Kaplan and Laura Marris’s States of Plague: Reading Albert Camus in a Pandemic (University of Chicago Press, October) “examines Albert Camus’s novel as a palimpsest of pandemic life, an uncannily relevant account of the psychology and politics of a public health crisis.” Writing during lockdown, with one of them sick with the coronavirus, the authors “find that their sense of Camus evolves under the force of a new reality, alongside the pressures of illness, recovery, concern, and care in their own lives.”

Circumstances push them to consider “how the novel’s original allegory might resonate for a new generation of readers who have experienced a global pandemic.” In the words of one of Camus’s favorite authors, William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”