You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

ilyast/Getty Images

A new working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research finds that students performed substantially worse, on average, on standardized course assessments at the end of the COVID-19 spring semester than in previous academic terms.

There was no evidence that this was driven by specific demographic groups, meaning that everyone was at an apparent disadvantage as a result of the rapid switch to remote instruction.

Professors’ use of active learning methods mitigated some of this negative effect, however. The findings leave the study’s authors “optimistic” about future student learning outcomes, even as “we remain in a period of substantial online instruction.”

“Online teaching experience seems to matter, and during Spring 2020 most college faculty accumulated substantial experience,” the researchers wrote of their outlook. Moreover, it’s “possible to incorporate peer interaction such as think-pair-share or small group activities into synchronous online courses,” and these teaching strategies are “significantly associated with improved learning during the remotely taught portion of the semester.”

Accurately assessing real student learning is challenging in the best of circumstances, note the authors, several of whom research and teach economics at Cornell University. Student learning in this study was measured using standard multiple-choice economics assessments developed through Cornell’s Active Learning Initiative, which is dedicated to using research-backed practices to improving undergraduate education.

In all the assessments used in the study, each question is linked to explicit course learning goals. They were administered to students as low-stakes tests around the end of the terms in question: spring 2019, fall 2019 and spring 2020.

Students in seven different undergraduate economics classes at four separate research universities participated in the study, completing these assessments along with a short demographic questionnaire.

At the end of spring 2020, professors for each of the seven courses also filled out a survey about their teaching practices and course material covered -- both before and during the pandemic.

All but one of the courses were taught by the same professor throughout the time period studied.

Six of the seven classes were taught synchronously during spring 2020, via Zoom lectures. The seventh instructor prerecorded lectures and spent scheduled class time on Zoom answering student questions.

Regarding active learning techniques, the researchers focused on two easily measured practices: the use of polling software, or “clickers,” for at least two questions during most class periods, and explicit group or peer interaction within the virtual classroom. Examples of peer interaction are think-pair-share activities with partners, small group activities, encouraging students to work together outside class time in preassigned groups and allowing students to work together on exams.

Asking students to answer conceptual questions or solve problems during class has been shown to improve outcomes in in-person classes “because it forces students to engage with the material and gives the instructor immediate feedback on what students have learned,” the study notes. “Having students work together to answer challenging questions and engage in ‘peer instruction’ has also been associated with positive student outcomes.”

Essentially, the researchers expected that learning would suffer during the pandemic but wanted to know who suffered most, and what pedagogical factors ameliorated the suffering.

Despite widespread fears disadvantaged students might fare more poorly during the COVID-19 spring term than their peers, none of the demographic groups studied experienced significantly different effects of the pandemic relative to white or Asian male students who had at least one parent with a college degree and spoke English as their native language.

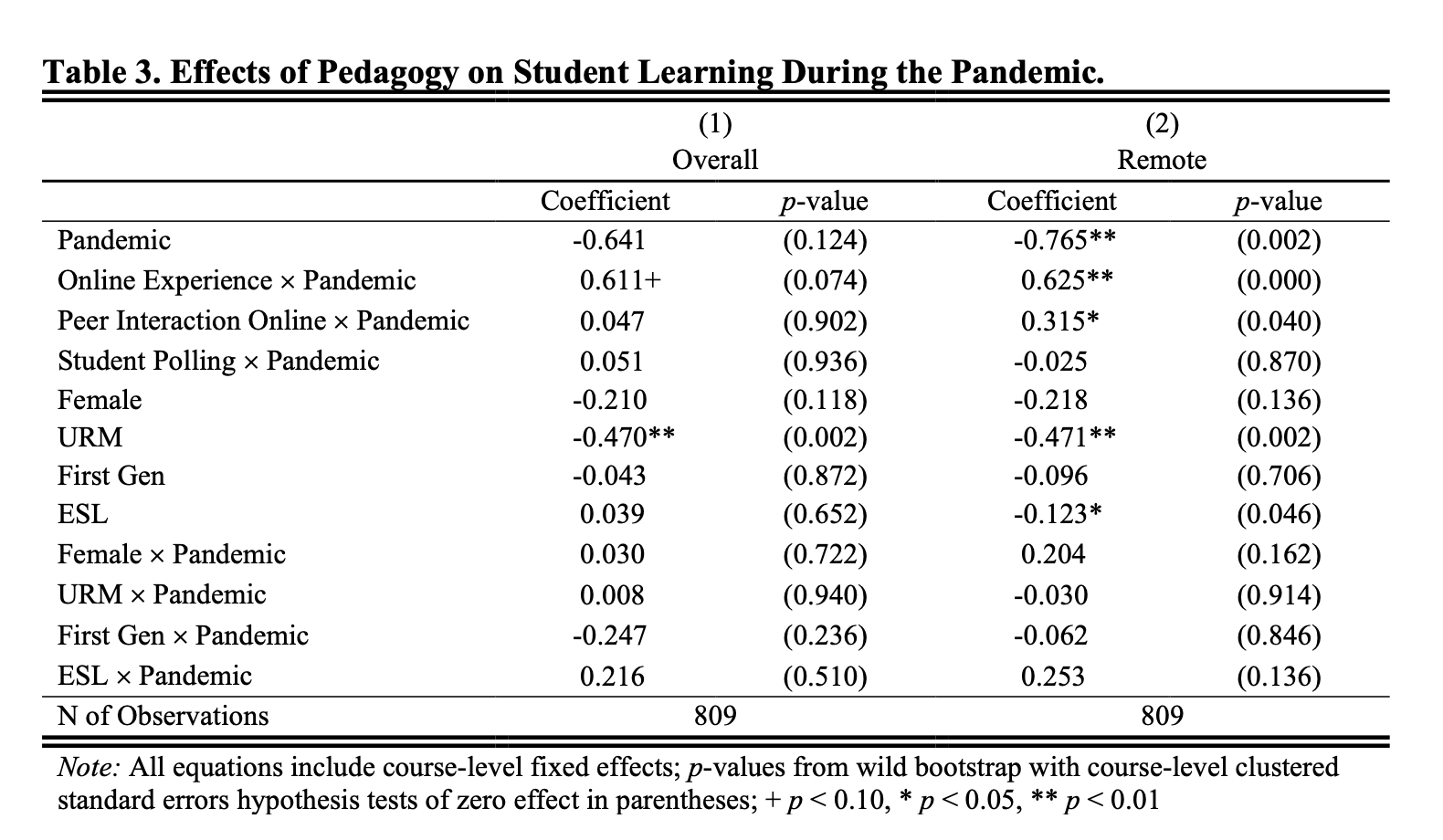

True to what the researchers expected, experience teaching online and course pedagogy played important roles in mitigating the negative effects of the pandemic on learning. When the instructor had prior online teaching experience, student assessment scores were significantly higher over all (0.611 SD, p=0.074) and for the remote material (0.625 SD, p=0.000).

Students in classes with planned peer interactions earned scores that were similar, relative to students in other classes on the overall scores and 0.315 SD higher (p=0.040) for the material taught remotely.

Polling, or clickers, meanwhile, didn’t seem to have much of an effect, either way.

Spring 2020 was, hopefully, a singular semester. So how relevant are these results to future online terms, even those where COVID-19 is still a factor, or a so-called new normal? Study co-author Douglas McKee, senior lecturer in economics at Cornell, said there’s no reason why his and his colleagues’ results shouldn’t continue to hold. While it's possible that the importance of “structured peer interaction will be lessened as students have had more time to build their own support networks,” he said, “explicitly building ties between students will continue to be very important in an online environment.” This is especially true for students studying away from campus, he added.

Online teaching experience will continue to matter, as well, McKee said. To that point, does the study have anything to say about the ongoing synchronous versus asynchronous instruction discussion? Facilitating peer-to-peer interaction is, in some ways, easier during synchronous classes.

McKee said that based on his personal experience, synchronous instruction "is more effective than asynchronous because it allows instructors to build peer interaction into the virtual classroom in a way that’s very similar to how it works in the physical classroom." This specific study "can’t really say anything about asynchronous teaching models," though, as it didn’t include any courses taught that way.

Christine Greenhow, associate professor of counseling, educational psychology and special education at Michigan State University and a longtime proponent of effective online teaching, said Monday that the rapid shift to remote instruction earlier this year was “far from ideal.” Now, however, she said, “it’s time for educators to take stock of what we have learned and use it to improve our teaching, online and off.”

On synchronous and asynchronous instruction, Greenhow said online learning experiences should combine both, along with "frequent, direct and meaningful interaction" between students and between students and professor.

Regarding this new study, in which she was not involved, Greenhow said that the findings on the power of peer interaction align with previous online learning research.

Teachers can indeed “facilitate active learning online where students are critically evaluating their work, connecting it to what they already know and reflecting on what they learned with their peers,” Greenhow said. “This can be done synchronously, in real time through social media, polling, online breakout rooms and other tools -- but also asynchronously online through collaboration tools that allow students to work at their own pace, on their own time but collectively produce work.”