You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

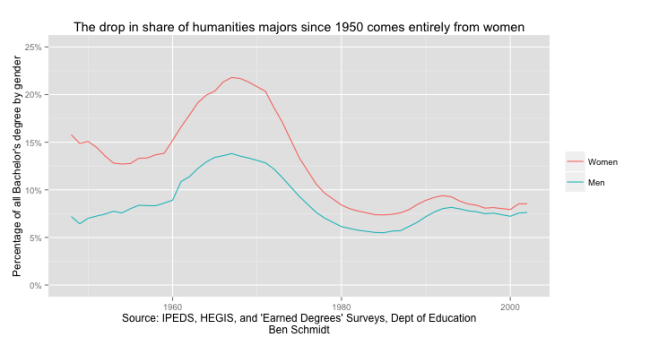

Ben Schmidt

There’s no shortage of explanations for the so-called crisis in the humanities, and more have come to light since the publication of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences' recent “Heart of the Matter” report on the topic.

But one higher education blogger’s unconventional explanation – that the humanities drain is more about women’s equality than a devaluation of the humanities – is gaining particular interest from longtime advocates of the humanities, as well as some criticism.

In recent posts to his blog, Sapping Attention, Ben Schmidt, a graduate student in history at Princeton University and visiting graduate fellow at the Cultural Observatory at Harvard University, argues that the decline in humanities majors since their 1970 peak can be attributed nearly entirely to the changing majors of women.

Based on data compiled for the academy's Humanities Indicators Project, he wrote, “I think it's safe to say that [the] ostensible reason for the long-term collapse in humanities enrollment has to do with the increasing choice of women to enter more pre-professional majors like business, communications, and social work in the aftermath of a) the opening of the workplace and b) universal coeducation suddenly making those degrees relevant.”

He continued: “You'd have to be pretty tone-deaf to point to their ability to make that choice as a sign of cultural malaise.”

Looking at the often-cited drop in humanities majors from 14 percent of all degrees granted some 40 years ago to 7 percent today as a whole, commentators such as David Brooks have attributed it to a disconnect with the current pedagogy. Others say that college students are increasingly career-oriented and so are rejecting degrees that don’t promise a job upon graduation.

But Schmidt comes to his conclusion by breaking down the numbers to show that the proportion of male graduates majoring in the humanities has declined from 13 to 7 percent from its peak in 1970 to today, a period in which overall enrollments and available fields of study both increased dramatically. At the same time, the proportion of women majors decreased more dramatically, from more than 20 percent to roughly the same percentage as their male counterparts today.

In an e-mail interview, Schmidt said despite the current discourse on the humanities, the only period they “collapsed” in terms of degrees granted was from 1970 to 1985. Part of that decline was due to the burst of the “boomer bubble,” he said, and almost all “the rest is because women started majoring in fields like business, engineering, and communications, which they had hardly done at all before.”

Women majors in pre-professional fields increased from less than 5 percent of all degrees earned by women in 1965 to more than 25 percent today. The trend was mirrored in reverse not just in the humanities but also in education; 40 percent of all women’s bachelor’s degrees were in education in 1965, compared to about 10 percent today. (Women majors in the social sciences increased somewhat, followed by the physical and biological sciences.)

About the same percentage of college men major in history, English, and philosophy now as did in the 1950s, Schmidt added. “So in some sense, complaints about the drop in female humanities majors since 1970 are really complaints that women are now going to college to improve their career prospects, just like men.”

David Laurence, director of research and of the Association of Departments of English for the Modern Language Association, has endorsed Schmidt’s idea on his blog, The Trend. Comparing the percentages of undergraduates receiving degrees in the humanities in the 1970s to today – as many have done in response to the “Heart of the Matter” report – is problematic in part because the “then” percentage value is “inflated by the high percentage of women who were, until the 1970s, a semi-captive audience for study in the humanities (and also in education),” he wrote.

For example, in the late 1960s, nearly 12 of every 100 degrees earned by women were in English, compared to 4.5 for men, he wrote. By 1983, four degrees out of every 100 earned by women were in English. The men’s numbers held relatively steady.

Opposite trends appear in the rate of business degrees awarded to women over the same period, he noted, further supporting Schmidt’s argument.

Christianne Corbett, senior research at the American Association of University Women, said she thought Schmidt’s premise seemed “reasonable,” as his data clearly show that from around 1975 to 1990, the percentage of women earning degrees in the liberal arts, particularly in the humanities, declined while those earning pre-professional degrees increased.

Although he called Schmidt’s claims that gender shifts could nearly entirely explain the phenomenon “reductionist,” Peter Wood, president of the National Association of Scholars, said the argument held value. It's “very plausible” that the increasing choice of women to enter more pre-professional majors has played an important role in the relative decline of humanities majors, he said.

“Cultural history is complicated stuff and, of course, it is often difficult to distinguish cause from effect and contributing factor from precipitating force,” Wood said. “[But the] flood of women in the 1960s out of teacher education programs is certainly clear and clearly related to the new kinds of career opportunities for women.”

Like some conservative commentators, however, Wood also noted that humanities instruction has changed so much in the past 50 years that comparing enrollment rates then and now “runs into and apples and oranges problem." Now mainly a "locus of cultural complaint by people recycling dull theories and identity politics,” the humanities that students began to reject in large numbers in the 1970s were not the same humanities that earlier generations favored, he said.

Gerald Graff, a professor of English and education at the University of Illinois at Chicago who has written extensively about humanities education, said Schmidt's argument challenges such assertions.

"I think there is something to this argument that it's the opening up of the sciences and other fields to women that accounts for most if not all of the drop in the humanities majors, and not some new form of rot" in those disciplines, said Graff, a former MLA president who coined the phrase "teaching the conflicts" to promote idea that debates that academic subjects provoke are a central part of the subjects themselves. "Those who blame recent trends on the academic humanities themselves seem to be to be using the decline in enrollments as an excuse to grind their axes."

Not everyone finds Schmidt's argument viable, however. William Chace, a professor emeritus of English and president emeritus of Emory University, pointed to a recent Harvard University report as contrary evidence. The report details long- and short-term shrinking undergraduate enrollments in the humanities at Harvard, largely due to increased enrollment in the social sciences.

Schmidt and those who have made similar arguments "are whistling by the graveyard, at least with respect to the trends, recent trends, at the most distinguished places" -- including Harvard, which people "look to as a flagship," said Chace. (The scholar has previously written about the decline of the humanities and English in particular. Similar to Wood, he blames new pedagogical approaches that have undermined tradition and alienated "young people interested in good books.")

Schmidt has addressed media coverage of that report on his blog, comparing the portrayal of the humanities to the "Roman Empire, teetering on a collapse precipitated by [humanities majors'] inability to get jobs like those computer scientists can provide." But Harvard isn't representative of all of American higher education, he said. And if "you look at all the universities, not just Harvard, the story is of stability since about 1980. Maybe there's a small drop in the last few years, but it's certainly nothing unprecedented."

All the more reason to break down the numbers, he said, as “commentators only want to tell long-term stories.”

“On the one hand, you have conservatives saying that the humanities started studying the wrong sorts of things, and that destroyed their enrollments, and you have professors worrying that it shows how true scholarship is being sidelined in the corporate university,” he said. But the data don’t support either argument.

“The bigger risk,” he said, “is that these conversations take for the granted that humanities degrees are the kiss of death when a student goes out to look for a job, which there is zero evidence for but could scare a lot of kids into not doing majors they’d like to do.”

Yoni Appelbaum, a Ph.D. candidate in history at Brandeis University and fellow cultural historian and blogger, said he hoped that Schmidt’s analysis of the long-term trends among humanities majors "will allow us to move past the panic over a mounting crisis, and on to a more careful consideration of the proper role of the humanities in higher education and in society at large.”

Whether the decline of humanities is real or exaggerated, Rosemary Feal, executive director of the MLA, said there’s reason to care about them today. “This is our cultural heritage,” she said. “We would be shortsighted to tie its study and preservation to the number of majors alone.”

But by studying the history of the debates around “so-called crises” in the humanities, she added, “we’ll understand why the cultural moment in which we find ourselves returns every 10 years or so with a new twist. The humanities at work!”

Appelbaum said Schmidt's "debunking" of the crisis itself provides a convincing case for the humanities. "After all, it took a humanist to extend our historical perspective, place the statistics within their proper context, and relate the raw numbers to broader social trends," he said.