You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

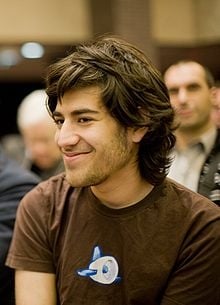

Aaron Swartz

Wikipedia

In a long-awaited report on its role in the federal case against Aaron Swartz, Massachusetts Institute of Technology acknowledges that it missed an opportunity to emerge as a leader in the national discussion on law and the Internet. But it denies any active role in his prosecution for the theft of millions of journal articles, as well as other “myths” that it targeted the cyber activist in the events leading up to his suicide in January.

“MIT took the position that U.S. vs. Swartz was simply a lawsuit to which it was not a party, although it did inform the U.S. Attorney’s office that the prosecution should not be under the impression that MIT wanted jail time for Aaron Swartz,” the report reads.

While that position may have been “prudent,” it says, “it did not duly take into account the wider background of information policy against which the prosecution played out and in which MIT people traditionally have been passionate leaders.”

MIT President L. Rafael Reif commissioned the report days after Swartz’s death in New York City, following public outcry from Swartz’s family and friends, in addition to MIT students and faculty and scores of supporters on the Internet. They said MIT hadn’t done enough to stop the federal case against Swartz, a former child prodigy and developer of Internet technology who believed deeply in the democratization of information and had downloaded articles from JSTOR in 2010 for that purpose, not personal gain.

A panel led by Hal Abelson, a professor of computer science engineering with a strong background in digital information sharing, prepared the report with the pledge from MIT leaders that the work would not be subject to administrative review. Initially slated to take a few weeks, the endeavor lasted six months and involved the review of 10,000 pages of documents and interviews with dozens of MIT faculty and administrators and others involved in the case. Abelson was assisted by Peter Diamond, professor emeritus of economics, and Andrew Grosso, a Washington lawyer with no other ties to MIT.

In a telephone interview with reporters on Tuesday, Reif said he read the report with “a deep sense of sadness for the loss of this brilliant young man,” and hoped that “some good” could come from the questions raised by the case.

For example, Reif said, the report argues that MIT should have seen the case not just as the prosecution of someone with no formal connection to MIT (Swartz was not a student), but as illustrative of the larger tensions in our society around open access and digital property in the digital age.

“That is a valid perspective and people will have different opinions,” he said.

The report also says that MIT “could have done more for the defense,” such as giving Swartz’s lawyers all evidence given to the prosecution, without waiting for a subpoena. The same goes for interviewing witnesses.

However, Reif said, “The report confirms that members of the MIT community involved in the Swartz case acted appropriately.” MIT at no time pushed for prosecution, opposed a plea deal or called in “the feds,” as has been alleged due to the Secret Service officer involved in that agency’s investigation of Swartz who arrived to arrest him along with Cambridge, Mass., police in 2011. A campus security official spotted someone who resembled the man in a video MIT was circulating of someone who had been downloading massive numbers of articles from the MIT network, and campus officials called local police to assist with the arrest, the report says. But MIT security had no idea who Swartz was at the time.

A federal grand jury indicted Swartz on felony charges in 2011 and a trial was scheduled for spring of this year. Authorities said that he was an unauthorized user of MIT’s network, and, if convicted, the 26-year old would have faced millions of dollars in fines and up to 30 years in prison. Swartz’s supporters criticized the severity of the penalties at the time, and MIT in its report refers to the prosecution as “overtly aggressive.”

A Whitewash?

Swartz’s friends and supporters immediately criticized MIT’s investigation.

His girlfriend, Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, slammed it as a “whitewashing” of MIT’s role on her blog.

“Here are the facts: This report claims that MIT was ‘neutral’ — but MIT’s lawyers gave prosecutors total access to witnesses and evidence, while refusing access to Aaron’s lawyers to the exact same witnesses and evidence,” she said. “That’s not neutral.”

She continued: “The fact is that all MIT had to do was say publicly, We don’t want this prosecution to go forward’ – and [federal prosecutors] Steve Heymann and Carmen Ortiz would have had no case. We have an institution to contrast MIT with – JSTOR, who came out immediately and publicly against the prosecution. Aaron would be alive today if MIT had acted as JSTOR did. MIT had a moral imperative to do so.”

The report finds that few on campus paid much attention to the case until Swartz's suicide, and opinions among those who were engaged varied widely. Although there were discussions about publicly opposing the prosecution, the report states, "there was a general agreement that he had done something wrong. A blanket statement opposing prosecution could have been perceived as extreme by many in the MIT community. Beyond that, a position opposed to any prosecution at all could have been interpreted by many people as saying that MIT was uninterested in respecting its contractual agreements with licensors and was not serious about maintaining the integrity of its network."

Stinebrickner-Kauffman also accused MIT of continuing to “stonewall” requests for information about the case, including Secret Service files on the case that have been the subject of a media open records request.

Asked about its recent move to block that request during the news conference, Grosso said MIT was not trying to withhold information but rather to preserve the privacy of individuals mentioned in those documents.

In a post to his blog, Swartz’s mentor, Lawrence Lessig, professor of law at Harvard University and director of its Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, said an initial read of the report revealed that MIT never told prosecutors that Swartz’s access to its network was unauthorized, but rather that his laptop was not supposed to be plugged into the Ethernet jack it was plugged into. That raises questions about the validity of the entire case against him, Lessig said.

“The whole predicate to the government’s case was that Aaron’s access to the network was ‘unauthorized,’ yet apparently in the many, many months during which the government was prosecuting, they were too busy to determine whether indeed, access to the network was ‘authorized.’ ….If indeed Aaron’s access was not ‘unauthorized’ — as Aaron’s team said from the start, and now MIT seems to acknowledge — then the tragedy of this prosecution has only increased.”

Demand Progress, a civil liberties watchdog group Swartz founded, and which now advocates "Aaron's Law" -- proposed changes to the federal Computer Fraud and Abuse Act that would no longer classify certain victimless Internet crimes as felonies -- called the report "fundamentally flawed."

"MIT does not seem to understand that a few, simple, reasonable actions would have saved Aaron's life," Charlie Furman, a group campaigner, said in a statement. "If the university had said publicly, 'We don't want this prosecution to go forward,' there would have been no case and Aaron would be alive today."

A spokeswoman for JSTOR said it had no immediate comment on the report, other than “it seems that MIT took this very seriously and that [Abelson] used a great deal of care in preparing this report.”

JSTOR, which early on in the case against Swartz said publicly that it had no interest in his prosecution, also made publicly available all the evidence it provided to the U.S. Attorney’s office in relation to the case.

The report includes a list of questions MIT will consider starting this fall, to become “more like the community we strive to be,” Abelson said:

- Should MIT develop additional on-campus expertise for handling potential computer crime incidents, thus giving the institute more flexibility in formulating its responses?

- Should MIT policies on the collection, provision, and retention of electronic records be reviewed?

- Should an MIT education address the personal ethics and legal obligations of technology empowerment?

- Should MIT increase its efforts to bring its considerable technical expertise and leadership to bear on the study of legal, policy, and societal impact of information and communications technology?

- What are MIT’s institutional interests in the debate over reforming the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act?

- Should MIT strengthen its activities in support of open access to scholarly publications?

- What are MIT’s obligations to members of our extended community?

- How can MIT draw lessons for its hacker culture from this experience?

Abelson said the question of the role of the institute in training students to “navigate” the intersection of ethics, law and the Internet was the most important. The Internet is an “enormous power” that can be used for tremendous good, but also for activities that become self-destructive, he said.