You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

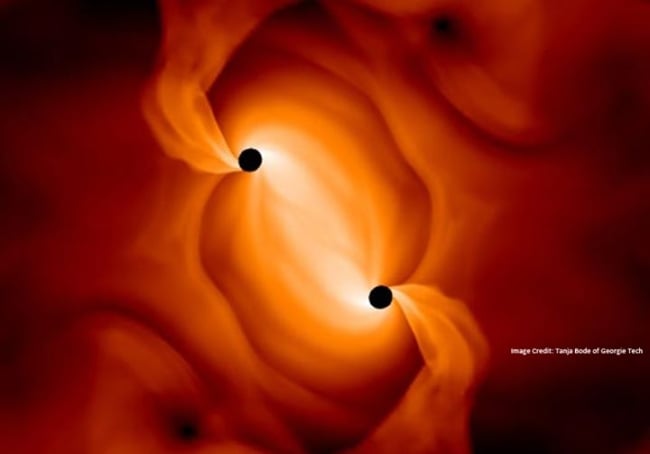

A computer-generated binary system of black holes orbiting around one another just before they merge.

Tanja Bode, Georgia Institute of Technology

If physicists ask some of the biggest possible questions about the nature of the universe, can a university exist without a physics department? A growing number of institutions think so, either cutting or combining programs. Citing budget concerns and low numbers of majors, the University of Southern Maine is the latest institution to consider eliminating its physics major.

Some proponents of the discipline say it’s a shortsighted move, and, like similar initiatives in other states, could contribute to the country’s dearth of qualified candidates for science-related jobs. The value of physics – a “foundational” science – isn’t tied to enrollment alone, they say.

Yet some of those proponents – along with critics – also say anger about department closures should be directed inward. Physicists need to address longstanding concerns about diversity within their ranks and better communicate the value of the discipline to the general public, they say. Better teaching and mentoring also could capture more student interest.

"It’s a mistake,” said Paul Nakroshis, an associate professor of physics at Southern Maine who has been involved in university discussions about cutting physics. Not only is it an essential part of a “comprehensive” university, physics is “excellent training for almost any scientific career because of its breadth. It spreads over many areas of technology, math and science.”

Without a physics major – and the upper-level courses that come with it – quality of study would decline, diminishing the university’s ability to attract talented students and faculty interested in physics and possibly science in general, and that’s bad for everyone, Nakroshis said. “Already in this country there are some pretty grim statistics in terms of how many people think the world is 6,000 years old and about [the validity of] global warming.”

But administrators, who instituted a “rule of five” several years ago to justify the closure of other departments graduating fewer than five majors annually, including Russian and German, say that physics simply isn’t attracting enough students. In a draft “action plan” presented last month, the university told the department – which graduates about three majors annually – to stop admitting new majors immediately; advise current majors on completing their course of study “as quickly as possible;” and to think about reorganizing itself into a new kind of science unit with “at least 20 faculty members" and some different focus by the end of this academic year.

The “necessity” of all physics courses will be assessed by the department and an outside curriculum developer, according to the plan. But lower-level courses will continue to be offered for students who need them to complete other majors, such as engineering. Students interested in majoring in physics can do so at the University of Maine at Orono, the state’s flagship institution, about three hours away.

Administrators say the plan was just a draft and that it was never meant to be shared publicly. But Nakroshis said there was little discussion at his meeting with the university provost, and the document seemed more like a plan ready for execution.

With other faculty and students voicing their concerns, the Faculty Senate voted overwhelmingly to “retract” the plan late last month, but it is unclear whether the administration will honor that vote.

Michael Stevenson, provost, said via e-mail that he is “initiating conversations with the faculty, the intent of which is to encourage faculty from physics and a range of complementary disciplines to think anew about how to offer a curriculum in the sciences that will attract, retain and graduate more students.”

The plan is an attempt to manage the university’s resources in the best, most responsible way, he said. “I have not asked the physics faculty to walk away from their discipline; I have asked them to help us integrate physics into a science program that will distinguish [Southern Maine] from our competitors and attract more students. In short, I want more students to become engaged in physics than is happening with the current major.”

Andrew Anderson, dean of the university’s College of Science, Technology, and Health, said in an e-mail interview that the University of Maine System’s Board of Trustees asked all institutions under its purview to review programs that graduate on average fewer than five majors annually, and that all academic programs are required to undergo periodic review.

“This also comes at a time a time when the institution faces fiscal and competitive challenges,” he said.

Asked if he worried that cutting a classic discipline such as physics would reflect poorly on Southern Maine, Anderson said: “The simple answer is ‘yes,’ especially for those interested in [science, technology, engineering and math education (STEM)] education. You hope that people understand why public universities are having such discussions.”

Nakroshis said some in Portland, Maine’s most populous city, are “outraged” by the threatened closure, and there has been a fair amount of public support for the targeted department. An editorial in the Portland Press Herald argued that not all departments can be assessed by the same metric, and that a university should find a way to pay for classes – even small ones – that are in “important” disciplines.

Physics faculty from Bowdoin College, a nearby private institution whose students may take physics classes at Southern Maine for transfer credit, sent an open letter to the university, expressing a similar sentiment. To apply the “rule of five” to physics programs across the country would mean closing more than two-thirds of all departments, “with serious consequences for our national competitiveness,” they said.

Derick Arel, a senior physics major, wrote in an op-ed in Southern Maine’s student newspaper, the Free Press: “Physics is the most fundamental of the sciences. It represents the quest to understand the deepest attainable truths about reality and life. Further, physics is a foundational science which supports other departments such as engineering, chemistry, even biology. A university which removes its physics department is crippling its STEM fields in the same way that removing the English department would cripple the humanities.”

But there’s also been public support for the university’s plan, including a recent editorial in the Bangor Daily News, which argued that it would be “irresponsible for the university to continue to offer a major that students aren’t choosing, especially when USM is part of a larger system that offers the subject.”

So-called “low-performing” programs have also been threatened – or eliminated – in at least nine other states in recent years, according to the American Physical Society, most notably Texas. In 2011, that state’s Higher Education Coordinating Board announced that it would begin phasing out up to 7 of its 24 public undergraduate physics programs for failing to graduate 25 majors every five years (about five annually). Six closures already have occurred, but eliminated departments have joined a consortium to offer upper-level courses and a bachelor of science in physics that stands to be one of the largest granters of the degree in the state. Instruction occurs via interactive video, with one professor teaching more than 20 students across multiple campuses. The seventh university combined it physics and math departments.

Because two of the cut programs were at Texas's historically black colleges and universities, the move worsened the widely acknowledged lack of diversity within the discipline, physics advocates said.

“There was a national outcry because there are so few of those programs and they produce a great percentage of the black baccalaureates in physics,” said Kelly Mack, vice president for undergraduate science education at the Association of American Colleges and Universities. Closing physics programs only can exacerbate the underrepresentation of minorities and women in the discipline, given the role that diverse role models “in the marketplace” have in attracting diverse students.

According to data from the American Physical Society, underrepresented minorities receive about 10 percent of the bachelor's degrees in physics given to U.S. citizens or permanent residents, with women earning about 20 percent of degrees.

The organization has several programs directly address these issues, and the numbers of women and Hispanic Americans in the discipline are on the rise.

But physics also faces another problem, advocates said: people don’t understand it.

Crystal Bailey, education and careers program manager at the society, said physics cuts are part of nationwide trend of "culling" costs in higher education. But “people making these decisions don’t have a sense of what physics departments actually are contributing, both in terms of educating a powerful STEM workforce in really important ways, and the amount of research dollars that that help physics departments, as well as their universities.”

At Southern Maine, Nakroshis said the department nets $300,000 annually, based on large enrollments in introductory-level courses and its relatively small number of faculty. Stevenson said via e-mail: "We could communicate back and forth and back and forth yet again on the dollar amounts generated by various financial formulas. Nobody quibbles with the fact that physics generates plenty of credit hours in service to students enrolled in the STEM disciplines. Nobody should argue with the fact that those courses must continue regardless."

Bailey, whose job centers on promoting the important of physics education, said physics is the most “fundamental” of all the sciences, and that many jobs await physics majors in the private sector; about half of all graduates find work in that arena, most in STEM – particularly in engineering and computer science. One-third go on to graduate school in physics and astronomy, and the rest go to graduate school in another scientific area.

But Carl Wieman, a Nobel Prize-winning professor of physics and education at Stanford University and former associate director of science at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, said physics departments face more than a public relations problem. Programs with unusually high numbers of majors tend to have faculty with a strong sense of purpose who view attracting and retaining students as a responsibility, he said, pointing to the widely cited SPIN-UP study on which he worked.

"What that study found was the departments and faculty in those highly successful schools felt a clear responsibility to recruit students to major in physics and make sure they were happy and successful after they became majors," he said in an e-mail. "The physics faculty in the comparison schools always saw the number of physics majors as someone else's problem and responsibility."

Professors in popular physics programs also have been shown to use engaging teaching methods that inspire students to continue on to upper-level courses, he said. Despite that, most professors continue to teach “very traditionally.”

Program closures should “signal” to the discipline “that a physics major should be seen as a responsibility, not an entitlement,” Wieman said. “I think the outrage expressed by the physics community when things like this happen, or the dropping of physics programs at schools in Texas due to low enrollment, is misplaced. The concerns should be directed inward, not outward.”

Closing the physics program at Southern Maine would only dramatically impact students who wish to major in it, “and apparently few students do,” Wieman said.

Bailey said Wieman was “absolutely right” that physics departments need to do a better job recruiting and mentoring students – even those who don’t express an interest in going on to graduate school to study physics. But “a lot of faculty are getting the message and working really hard to change things,” sometimes against the trenchant attitudes of older faculty – and closing programs won’t help them evolve.

Physics unsupported by a department – at Southern Maine and elsewhere – would atrophy, she said.

Mack, of the Association of American Colleges and Universities, said physicists need to do a better job of promoting their discipline in a variety of ways. But they also face external challenges, such as students coming out of high school underprepared for the kind of math that physics requires.

Nakroshis also said students are coming out of high school underprepared for physics, given that only about one-third of high school physics teachers have physics backgrounds. Sadly, he said, a planned branch of a feeder program for physics majors to become high school physics teachers in the state would die at Southern Maine as a result of the plan.

The physics department at Southern Maine is small, with four faculty members. But Mack said its threatened closure and the closure of others like it have big implications. The country needs 1 million new STEM majors in the next 10 years, according to a recent report by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, she said, and it sets a disturbing precedent for other traditionally low-enrollment programs.

“Today it’s physics, tomorrow it could be mathematics,” she said.