You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Senate Republicans released their proposal for overhauling higher education late Tuesday night.

Kayla Bartkowski/Getty Images

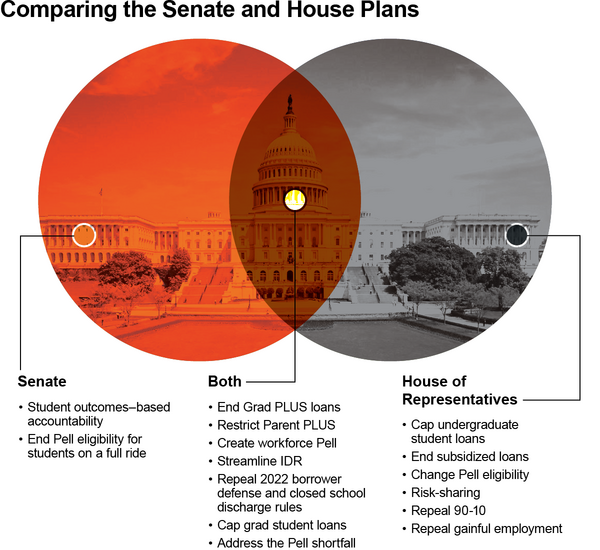

Both chambers of Congress have now outlined their higher education budget proposals, giving colleges a clearer sense of the scope and impact of what would be a sweeping federal student aid overhaul.

The Senate version, released late Tuesday night, is largely similar to the House’s proposal, which prompted widespread condemnation from student aid advocates when it passed in late May. Both would cap graduate loans, open up the Pell Grant program to short-term programs and cut all but one option for income-driven loan repayment.

But the Senate proposal includes a few key differences that have quelled some of higher education leaders’ most dire concerns—at least for now.

Most notably, the Senate bill does not include a limit on traditional Pell Grant eligibility that would have excluded thousands of part-time students, as the House version did, and it walks back the House’s controversial risk-sharing plan, which would force colleges to pay a penalty based on students’ unpaid loans.

“This bill is an improvement from the House’s version, and we acknowledge that the Senate listened to the higher education community,” said Emmanual Guillory, senior director of government relations at the American Council on Education. But over all, “this bill is still going to have an impact on access to postsecondary education, and that will be reduced access for low-income students.”

As the two chambers seek to reconcile their versions of the so-called One Big Beautiful Bill Act, many of the proposals are still up in the air, and it’s not clear how much House Republicans will fight for their more drastic changes. Regardless, with the Senate permitting some of the most consequential proposals, the final bill will almost certainly upend the federal financial aid system.

Sen. Bill Cassidy, a Louisiana Republican and one of the bill’s sponsors, said in a news release that the legislation would help “fix the broken higher education system that continues to fail students” and tackle “the root causes of the student debt crisis.”

Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed

Policy analysts say that the bill is a strong step forward in terms of holding all colleges accountable for delivering quality programs.

“The proposals in the Senate bill are much easier to understand and allow students and schools to get a sense of the consequences,” said Michelle Dimino, education director at Third Way, a left-leaning think tank. “It definitely makes significant changes to the borrowing landscape … but on the whole, it promotes stronger institutional outcomes.”

Still, student advocacy groups argue that even the Senate bill will harm millions of students and borrowers.

Sameer Gadkaree, president of the Institute for College Access & Success, wrote in a statement that the bill “would cause widespread harm to American families by making college more expensive, [and] making student debt much harder to repay.”

The Senate may have pared back some of the most detrimental changes, he added, but “the bill still harms the lowest-income loan borrowers and students to pay for tax cuts.”

What’s Different

In many ways, the high chamber’s proposal mirrors its low-chamber counterpart, but there are several notable differences.

For instance, the Senate scrapped a House plan that would require colleges to have skin in the game when it comes to covering unpaid student loans, preferring instead to tie colleges’ access to federal student loans to students’ earnings after graduation. Under the Senate’s plan, undergraduate programs could lose aid eligibility if their students earn less than an adult with a high school diploma. For graduate and professional programs, student earnings would be compared with bachelor’s degree holders.

“The risk-sharing approach is a back-end attempt at accountability,” Dimino said. Whereas “the proposal in the Senate bill takes the opposite approach of looking at up-front accountability by measuring earnings.”

Dimino believes that this proposal, which is similar to the Biden-era gainful-employment rule, is the better of the two options.

“It’s serving students better by ensuring that they are only permitted to borrow federal loans or go to programs that can meet those standards of quality based on earnings,” she said. “And makes it a little bit easier for institutions to plan as well.”

But Preston Cooper, senior fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, feels the House proposal for risk-sharing is a more effective incentive for colleges to lower costs and limit students’ debt than a reworked gainful measure.

The Senate version “will take care of the egregious programs that have terrible earnings outcomes, but not the programs that have medium earnings outcomes but big debt burdens,” he said.

The bill also protects the Pell Grant program. Under the House’s proposal, the amount of coursework required to receive a maximum grant would increase from 12 to 15 credit hours per semester; for students enrolled in fewer than 7.5 credit hours, grant access would be completely cut off. A Center for American Progress report estimated that as many as four million students would be affected.

“We had real concerns that the bill could likely include the Pell eligibility changes that the House bill included. So when we met with them, we led with that,” said Guillory.

On top of protecting Pell, the Senate bill maintains subsidized loans and doesn’t limit undergraduate borrowing. Higher ed lobbyists were generally pleased to see these changes, but they were still hesitant to support the restrictions that remained—specifically caps on how much graduate and professional students can borrow. The Senate’s loan caps for postbaccalaureate programs were also slightly different from those proposed in the House.

Finally, the Senate version would preserve a regulation that protects veteran students from predatory for-profit programs, which the House sought to eliminate, and it does not include the House’s proposed new formula for calculating and comparing median program costs, which many college access advocates said would make paying for college more confusing for families.

What’s Next

Several of the House provisions, however, were practically untouched by the Senate, and policy experts say those are highly likely to be included in a final version of the reconciliation bill.

One such provision is workforce Pell, which would expand grant eligibility to short-term credential programs that run from eight to 15 weeks. It would largely benefit community colleges, which are the primary providers of accredited short-term programs, but the provision could also grant access to a number of unaccredited programs, potentially upending the fast-growing credential market.

It has garnered support from community college organizations that have supported such an expansion for years. But they also have their concerns: Carrie Warick-Smith, vice president for public policy at the Association of Community College Trustees, said the organization supports the expansion but is opposed to Congress’s inclusion of “entities that do not qualify as institutions of higher education.”

Originally President Donald Trump had set an ambitious July 4 deadline. But some senators have warned that’s a tall order. Sen. Ted Cruz, a Texas Republican, told Punchbowl News on Wednesday there’s “no way” that will happen and that the bill is more likely to reach the president’s desk in August.

For the most part, experts say that without a crystal ball it’s difficult to predict which provisions will stick. But Cooper said the area most likely to inspire a cross-chamber legislative fight and drag out the bill’s passage is the difference in college accountability measures, as “folks in the House are very excited about risk-sharing, and the Senate earnings test might not pass muster with them.”

At the end of the day, negotiations will likely hinge on the pure spending total of the bill, he explained. The House plan would save about $350 billion over 10 years, while the Senate bill saves an estimated $300 billion.

“The debate here is going to come down to ‘How much money do we actually want to save?’” Cooper said. “The tug-of-war between the chambers is going to really hinge on that.”