You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

“[T]hey can employ not just metaphor, but caricature, which can be harsh… Humor, mockery, satire. People don’t like to be made fun of. They don’t like their views to be made fun of, they don’t like their religion to be made fun of. And sometimes they perceive a harsh personal insult where one is not intended, or maybe where one is intended.”

That’s how Steve Sack, a Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist for The Minneapolis Star-Tribune, described the political minefield in which cartoonists work during a Jan. 29 panel on free speech and satire at the University of Minnesota, in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris. Sack’s words also foreshadowed a later debate over how the panel was advertised, which until now has been kept out of the public sphere.

When Muslim students complained about posters that promoted the event, the university investigated their concerns and issued a report that questioned the judgment of those who signed off on the posters. And the university sent an email that some interpreted as an order to remove the posters, although the university disputes this.

The discussion raises questions about how colleges and universities should balance their commitments to academic freedom and free speech with the cultural sensitivities of students and others involved in campus life. And like the recent PEN award protests over a planned tribute to Charlie Hebdo, it’s also a reminder of how controversial the magazine and what it stands for remain, and how the attack continues to reverberate among thinkers across continents.

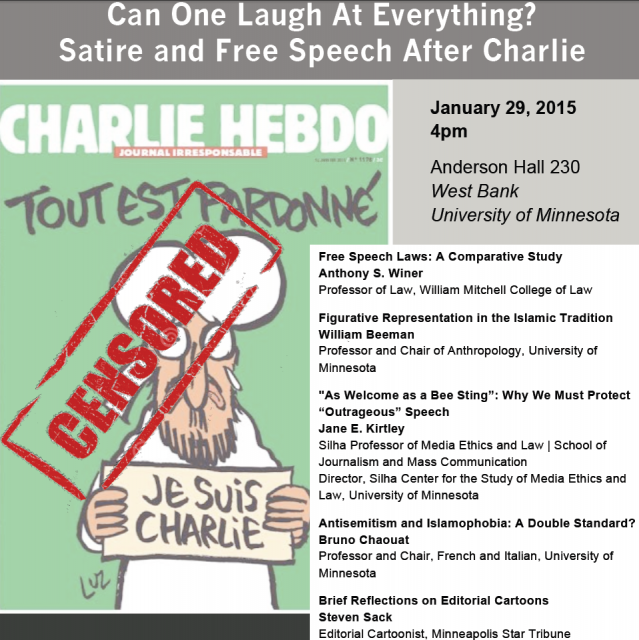

Like academics on many campuses, professors at Minnesota grappled with how to talk about the mid-January shootings of staff members at the satiric newspaper, known for its in-your-face irreverence to authority of all kinds -- including religious. Hoping to provide a space for dialogue, by the end of the month several professors had organized a panel called “Can One Laugh at Everything? Satire and Free Speech After Charlie.”

The panel included Sack, who reflected on being a cartoonist, and several Minnesota professors. Anthony Winer, a professor of law, offered a comparative study of free speech laws. Jane E. Kirtley, the Silha Professor of Media Ethics and Law and director of the Center for the Study of Media Ethics and Law, delivered a talk called, “As Welcome as a Bee Sting: Why We Must Protect ‘Outrageous’ Speech," while William Beeman, professor and chair of anthropology, talked about figurative representations in the Islamic tradition -- including lesser-known historical depictions of Muhammad. Most observant Muslims now consider any kind of physical representation of Muhammad off-limits.

Bruno Chaouat, professor and chair of French and Italian, co-organized the panel and spoke on what he perceived as a possible double standard between anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, drawing parallels between violent Islamic extremism and Nazism (much of Chaouat’s work centers on the Holocaust). Another organizer, Riv-Ellen Prell, a professor and chair of American studies and director of the Center for Jewish Studies, introduced the panel. The event was cosponsored by 12 academic units in the College of Liberal Arts.

The organizers advertised the panel with a flyer featuring the cover of the Charlie Hebdo edition published immediately after the terrorist attack. In contrast to the magazine's earlier, at times vulgar depictions of the prophet, the cover shows a bearded man with a turban -- almost certainly intended to be but not explicitly labeled as Muhammad -- shedding a single tear. The headline is “Tout est pardonné,” or “All is forgiven,” and the man is holding a sign that says, “Je Suis Charlie,” or “I Am Charlie," a popular pro-magazine protest phrase following the attack. Over the image, the organizers put a red “censored” stamp-like image, which did not originally appear on the Charlie Hebdo cover.

They discussed the possible negative impact of publishing a picture of Muhammad on the flyer, given the prohibition against physical representations. But the organizers decided that doing so was appropriate for the event on free speech, according to a university account, and might also lead to more Muslim students attending. The flyer was published on the various unit sponsors’ websites and elsewhere on campus.

By panelists’ accounts, the event was a success, stirring debate about the limits, if any, of free speech in light of the events at Charlie Hebdo. Not everyone agreed with the speakers, and several audience members pointed out that the panel did not include a Muslim. But the conversations remained principled, if at times impassioned.

By panelists’ accounts, the event was a success, stirring debate about the limits, if any, of free speech in light of the events at Charlie Hebdo. Not everyone agreed with the speakers, and several audience members pointed out that the panel did not include a Muslim. But the conversations remained principled, if at times impassioned.

“The forum achieved its purpose,” said Beeman, the anthropologist. “It was not heated and most people thought it was quite valuable. …This is part of our role as educators, to help students and the public as well understand the full context of these sorts of controversies.”

Kirtley, the media law scholar, described the event as standing room only, with “lively discussion” that was “not remotely hostile -- there was no one complaining and there were quite a few students who self-identified as Muslim.” Audience members and panelists continued to talk informally long after the scheduled end of the event.

So panelists were surprised to learn weeks later that complaints had been filed with the university’s Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action. The complaints were targeted at Chaouat and Prell as organizers, and referred not so much to the event itself as the poster advertising it.

According to a summary of the office’s investigation prepared for John Coleman, dean of the liberal arts, eight people -- four students, a retired professor, an adjunct professor and two others from outside the university -- contacted equal opportunity personnel to express concern that the flyer “featured a depiction of Muhammad, which they and many other Muslims consider blasphemous and/or insulting.”

The fact that “Charlie Hebdo originally created the image of Muhammad added to the insult, because [the magazine] has previously printed cartoons deliberately mocking Muhammad, including some depicting Muhammad naked and in sexual poses,” the summary continues. “This led some complainants [to] conclude that the [college or cosponsoring academic units] and the professors involved in organizing and promoting the event do not care about Muslims on campus.”

The office also received a petition signed by about 260 Muslim students, several staff members and about 45 people with no affiliation with the university. The petition says, in part, that the flyer is “very offensive” and has “violated our religious identity and hurt our deeply held religious affiliations for our beloved prophet (peace be upon him). Knowing that these caricatures hurt and are condemned by 1.75 billion Muslims in the world, the university should not have recirculated/reproduced them.”

Equal opportunity administrators conducted a formal investigation based on the complaint, including interviews with the event organizers. According the investigation summary, organizers “collectively reported that they chose to reprint the Charlie Hebdo image to express a commitment to the future of [the magazine] and to free speech generally, to condemn terror and to show Muhammad expressing love and compassion.” Moreover, organizers said, the image already had been published by news organizations worldwide. They also expressed a belief that “their dissemination of the flyer is protected speech under the First Amendment and principles of academic freedom.”

Ultimately, the office determined that the poster did not violate the university’s antiharassment policy, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of religion. Factoring into the decision was the poster’s relevance to academic subjects and its general commentary on a matter of public concern.

However, the office said in its summary for the dean, the poster had “significant negative repercussions.” And given the “large-scale” global protests against the image in question, “the organizers knew or should have known” that their decision to reprint the image “would offend, insult and alienate some not-insignificant proportion of the university’s Muslim community on the basis of their religious identity,” the office added. It said the hurt was heightened by the fact that the insulting speech came from those with “positional power” at Minnesota.

Consequently, the office wrote, “university members should condemn insults made to a religious community in the name of free speech.” Equal opportunity administrators told Coleman that he had the “opportunity to lead in creating an inclusive and welcoming environment for Muslim students by adding your own speech to the dialogue advocating for civility and respect by [college] faculty.” The office recommended that Coleman communicate the college’s disapproval of the flyer and “otherwise use your leadership role to repair the damage that the flyer caused to the relationship between [the college] and Muslim students and community members.”

Coleman received that recommendation at the end of March. What happened in the interim, as the investigation was ongoing, is somewhat in dispute. Chaouat and other panelists said administrative staff members in units that sponsored the event received an email from the university asking them to take down any remaining event posters. Some faculty members said links to the flyer on departmental web pages were broken as result. Both the content of the alleged order and the fact that the faculty organizers hadn’t been copied riled some, who complained to Coleman. But Kelly O’Brien, a college spokeswoman, said the college at no point told staff members to take the posters down, and that none were taken down. Rather, she said, the college automatically shifts past event notices off current web pages and into digital archives.

According to a heavily redacted series of emails between Coleman, various faculty members and equal opportunity administrators provided to Inside Higher Ed by the university, staff members received a message from the college human resources office on Feb. 13. The email includes a link to the digital flyer, noting that the free speech event "took place several weeks ago." It continues: "Due to complaints about the image contained in the link, [the equal opportunity office] has requested that the image be removed from any [college] communication in all forms. If your unit still has active links to this page, or image, please remove the image. Please remove any posters on your unit bulletin boards or any other hard copies of flyers that may be still around."

Coleman responded to various faculty concerns about censorship with a clarification letter of sorts on Feb. 16, saying that the earlier email from human resources “conveyed that there had been complaints about the continued presence of the posters and the image and intended to suggest that removing the advertising for a past event might be a possible response to some of the complaints that had been received. Whether you decide to remove the advertisement is your call.”

The dean wrote that academic freedom and free speech were “paramount values” for him personally, and that his own research in political science has often touched on those issues. That said, he concluded, “With the event now past, should [the poster] remain online, given the context of genuine hurt some individuals express about the image? The reasonable people, each an ardent free speech supporter, could hold some different views on that question, especially as it intersects with our desire to improve upon and deepen a welcoming campus climate.”

The investigation came to light last week in an article in the student newspaper, the Minnesota Daily. Prell declined to answer questions about the investigation, but said the event itself went “exceedingly well.”

In a brief interview, Chaouat said he feared it was possible that “terror and terrorism actually work when people have a tendency to internalize the fear of retaliation and to self-censor. …This is something that’s happened in France after the January events -- there’s been a lot of self-censorship in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks and I’m afraid we’re on the path here as well.”

He added, “In the name of tolerance and acceptance and diversity, we’re actually lying to ourselves.”

Beeman said he saw the events at Minnesota as part of a growing movement on college campuses “to enjoin faculty from saying anything that might hurt somebody’s feelings, or that might offend someone.”

For example, he said, he was teaching a course that mentioned witchcraft -- a technical term in his discipline -- and was approached by three Wiccans after class who said they were hurt by the term. Another student in another course on human evolution failed and then blamed her performance on the class material on race -- namely that it isn't a biologically solid concept --only to take it over again and fail once more, he said. There are also increased calls for trigger warnings and big pushes to block controversial convocation speakers from appearing on colleges campuses across the country. (Indeed, in one of the redacted emails to an unknown recipient, Coleman mentions possibly publishing a trigger warning with remaining copies of the poster. "I not infrequently will come across news sites that will provide the option of seeing/hearing something that might be considered difficult for some viewers/listeners," he wrote.)

But at least in some of those cases, Beeman said, the students approached faculty members directly to voice their concerns. Beeman said he wondered if the students involved in the Charlie Hebdo complaint understood the weight of launching a formal investigation before first trying to remedy the situation with the parties involved. His more “cynical” side says that “students have learned that they can exercise a certain amount of power by invoking the fact that they were offended by something or insulted.”

The Muslim Students Association at Minnesota did not immediately respond to an emailed request for comment.

Samantha Harris, director of policy research for the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, said she didn’t have detailed knowledge of the case. But she said she was “troubled by the university [equal opportunity office's] apparent request -- despite correctly finding that the posters did not constitute harassment -- that [Coleman] ‘voice disapproval’ of the flyer.”

While it would be within the dean's own free speech rights to criticize the flyer of his own accord, Harris added via email, “the university administration should not be pressuring him to be a mouthpiece for views that are not his own, particularly in light of the fact that a condemnation from the dean would likely have a chilling effect on future expression of this sort.”