You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

For decades, the federal government’s main yardstick for judging how colleges perform with federal aid dollars has been the default rate on student loans. Each year the U.S. Department of Education tallies up how many borrowers from a given college fell so far behind on their federal loan payments that they defaulted within several years of starting to repay.

But for every borrower who defaults on a student loan, there are many more who are unable to make progress in repaying their loans and are watching their balances grow, years after attending college, according to data released this month by the Obama administration.

More than one out of every three student loan borrowers nationwide failed to make any progress repaying his or her loans within three years, according to the data. By contrast, the national three-year default rate on federal loans was 13.7 percent last year.

The administration’s new data on loan repayment arrive as enthusiasm is building for using loan repayment rates as a more comprehensive metric to judge colleges.

There is a growing consensus among policy makers and others that colleges should be held accountable not only for educating students who are able to stay out of default on their loans -- but also for educating students who are able to make some progress in paying down their debt after leaving a college.

“Now that we have the data, the issue is, what do we do with it?” said José Luis Santos, vice president of higher education policy and practice at the Education Trust, an advocacy group that has called for higher minimum standards for colleges that want federal aid. “We’re certainly going to use it as a lever to influence Congress, and the public, to demand that we hold institutions accountable."

In releasing the loan-repayment information, as well as a trove of other new data about colleges, the White House generally avoided drawing conclusions about which colleges are doing well and which ones aren’t. Such was President Obama’s original plan in proposing a federal college ratings system, but the administration abandoned the idea after significant backlash from colleges and universities and members of Congress.

Repayment Rate Data

Click here for an interactive chart based on an Inside Higher Ed analysis, which shows 347 institutions where half of federal student loan borrowers had not made a single dollar of progress in paying down their loans seven years after they became due.

Download the full database of federal loan repayment rates for more than 4,000 institutions by clicking here.

Still, the release of the data nonetheless will add to a growing conversation in Washington about how to hold colleges more accountable for student outcomes, observers said.

Some have disputed the quality of the government’s new postcollege-earnings data -- it includes only federally aided students and is aggregated across varying majors and types of degrees -- and also questioned the wisdom of telling prospective students to make college decisions based on how much they might earn. By contrast, the repayment information, many data experts said, is more comprehensive and reliable. And it reflects a more straightforward way of judging colleges: Are former students repaying their loans?

While there had been budding interest in using loan repayment rates to gauge a more complete picture of students’ postcollege outcomes, the release of the administration’s College Scorecard data adds a new level of detail to that debate.

And the White House’s release of the data -- as well as its acknowledgment in accompanying reports of the weakness of the current default rate metric, which colleges can game -- also throws its political support behind the idea of loan repayment being a valid metric of a college’s performance.

The data show, for the first time, how many borrowers at a given college are making progress on their federal loans. At nearly 350 colleges, more than half of loan borrowers fail to make a single dollar in progress toward paying down their principal loan balance, even when measured by the more generous seven-year time frame in the database (see box).

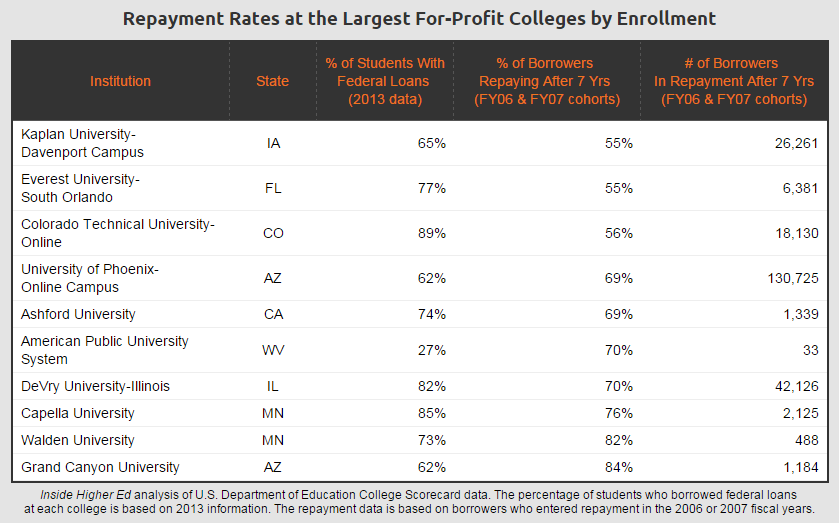

An Inside Higher Ed analysis of colleges where most students take out loans -- meaning that the repayment data describe the performance of a majority of students -- shows that for-profit colleges are among the worst performers, as are some community colleges and historically black colleges and universities. Among four-year, private nonprofit colleges where a majority of students borrow, HBCUs account for seven of the top 10 institutions with the lowest repayment rates.

Some of the repayment data for large for-profit education companies will likely provide new fodder for their critics. For example, 42 percent of students who attended ITT Technical Institute had not made a single dollar of progress on their student loans after seven years. At the University of Phoenix, that nonrepayment rate after seven years is 32 percent.

Despite the large shares of students at some colleges who end up failing to repay a single dollar of their loan principal, that type of problem is not fully captured by the institutions’ student loan default rates. Nearly all of the colleges with the worst repayment rates based on the new data have been meeting the government’s current default rate standards. And that means the institutions are able to accept federal student loans -- to the tune of $2.2 billion last year, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis published earlier this month.

Problems With Default Rates

Some of the interest in repayment rates is being driven by dissatisfaction with the current loan default rates as a legitimate measure of student outcomes.

Consumer advocates have long complained that the current default rate methodology, which keeps track of defaults three years after a loan enters repayment, is easily gamed by colleges that delay defaults by pushing students into deferment or forbearance until after the three-year window ends.

The White House’s technical analysis of the new data says that its loan repayment rate “is meant to be less susceptible to gaming behavior by institutions.”

Responding to critics of for-profit colleges, Congress in 2008 tightened the default rate standard -- holding colleges responsible for their former students’ defaults for three years instead of two years -- but critics argue the default rates are far too weak a tool to hold poor-performing institutions accountable.

The proof, some say, is in the results: the department has yanked the federal funding of just 11 colleges -- out of the nation’s roughly 7,000 -- because of high default rates over the last decade.

Reaction From Higher Ed

Switching to repayment rates as a primary accountability tool also has some support from within higher education.

Many public university leaders have said they would favor the federal government holding institutions more accountable for student outcomes like loan repayment rates. The Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, for instance, has called for tougher standards for colleges to get access to federal aid, based in part on repayment rates.

Still, some community college advocates worry that a loan repayment standard will bring about what they view as the same problems with the current federal default rates, and to a lesser extent, the debt metrics in the administration’s employment rule that applies to some of their programs.

That issue, they say, is that few students at most community colleges tend to take out loans to pay for college. And looking at how those loans perform provides an incomplete picture of how most of their students perform.

“That’s something we would worry about, whether a repayment rate would provide the same opportunities for community colleges to avoid sanctions because so few of their students borrow,” said David Baime, senior vice president for government relations and research at the American Association of Community Colleges.

But even among the handful of community colleges where, atypically, larger shares of students take out federal loans, the new data show that many are failing to make progress in repaying them. For example, at Navarro College, a community college in Texas, more than one-third of students borrow federal dollars. And nearly half of borrowers who attended Navarro had failed to pay down a single dollar of their loan principal balance after seven years.

Bipartisan Support

On Capitol Hill, lawmakers from both parties have said they’re interested in finding new ways to hold colleges more accountable for the federal money they use. As part of those discussions -- much of which have focused on various proposals for risk sharing -- the repayment rate has emerged as a key metric.

Senator Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, the Republican who chairs the Senate’s education committee, has indicated he’s interested in the concept of holding colleges responsible for their repayment rates.

In a white paper outlining his ideas for a rewrite of the Higher Education Act, Alexander’s staff said the current default rate standard isn’t “particularly effective.” Loan repayment rates could be one metric as part of a risk-sharing system, the paper said, floating a 50 percent repayment rate as a possible threshold for when colleges would start getting in trouble.

In addition, a bipartisan risk-sharing proposal introduced earlier this summer -- which both Alexander and Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton praised -- would overhaul the current default rate standard and replace it with a repayment rate metric.

Drawing Bright Lines

Some advocates for greater accountability for colleges say the new repayment data make a clear case for the federal government drawing brighter lines around what are acceptable student outcomes.

“All the hubbub has really been around the actual release of the data, and the transparency,” said Santos, of the Education Trust. “But the data alone does not change the overall outcomes, and it does not demand for institutions to do a better job.”

Ben Miller, senior director for postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress, said the Scorecard data are “a very serious endorsement of the idea” of using repayment rates to judge colleges.

How and where to draw those lines will be challenging, he said, as will determining what successful loan repayment rates ought to be.

The administration’s rate -- which looks at whether borrowers make one dollar of progress on their loans -- is far too low a bar, Miller said.

“Yes, we have a repayment rate now, but this rate lets through behavior that isn't even close to real repayment,” he said. “I would want something more ambitious that looks at whether you’re reducing your balance. Are you making progress towards balance in some reasonable amount of time?”

The politics of drawing tougher standards along repayment rates can be dicey. The last time the Obama administration tried to incorporate repayment rates was during its first attempt at writing a gainful employment rule. A federal judge later dismissed the resulting 35 percent repayment threshold as arbitrary. It was dropped from the final version of the rule that is now in effect.

Congress, of course, would be free to set whatever threshold it chooses for a repayment rate. That could be years away, but in the meantime, the repayment data offers a new tool for advocates, journalists and others to shine a light on colleges where graduates and dropouts fail to make a dent in their student loans.

.gif)