You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The nation’s name-brand colleges have made virtually no progress in admitting more low-income students over the last decade, according to the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, which is calling for a “poverty preference” in college admissions.

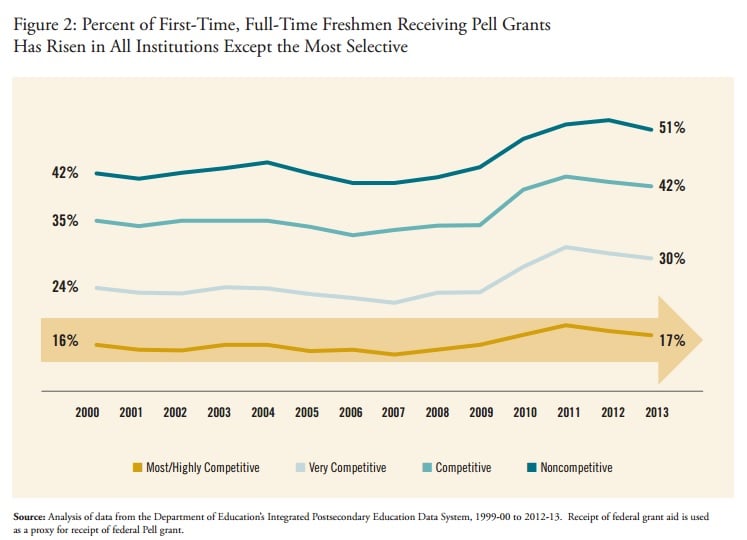

In 2013 Pell Grant recipients accounted for 17 percent of first-time, full-time students at the 193 institutions with the most competitive admissions, according to the foundation, which crunched federal data for a newly released report. That was up one percentage point from 16 percent in 2000.

In contrast, colleges described as having competitive admissions increased their Pell Grant recipient percentage to 42 percent from 35 percent over that same period.

“College admissions for kids in poverty is profoundly unfair,” said Harold O. Levy, the foundation’s executive director, in an interview Monday with journalists.

The report says many public colleges have begun a low-income preference in their application process. That move may become more important if the U.S. Supreme Court strikes down race-conscious admissions, Levy said. Either way, he said other selective institutions should follow suit. “It’s leveling the playing field.”

Many academically qualified students from low-income backgrounds fail to apply to selective colleges, a problem often dubbed “undermatching.” The report found that high-achieving, high-income students are twice as likely to apply to at least one selective college as are their low-income peers.

Needier students often get poor admissions counseling from high school guidance offices, Levy said, where student-to-counselor ratios can be 500 to 1, or higher. Many students from low-income families also are scared away by the sky-high sticker prices of elite colleges, and often fail to understand how financial aid works.

The college admissions system is rigged against low-income applicants in many ways, said Levy, from the test prep wealthy students get to legacy admissions and so-called merit aid, which is frequently an attempt to attract middle- and upper-class students to attend one college instead of another.

Even so, most top colleges claim they are committed to economic diversity on their campuses. “That’s so much blather,” said Levy. The numbers back him up.

Students from households in the bottom income quartile make up just 3 percent of enrollment at the nation’s most competitive colleges, the report said. But 72 percent of enrollment at these colleges is comprised of students from the wealthiest quartile.

The foundation’s report said selective colleges need not lower their admissions requirements to enroll more low-income students.

“Hidden within these numbers are thousands of students from economically disadvantaged households who, despite attending less-resourced schools and growing up with less intellectual stimulation and advantages, do extremely well in school, love learning, are extraordinarily bright and capable, and would do very well at selective institutions if offered admissions,” the report said. “They are just being ignored.”

The foundation cited research that found that highly selective institutions could increase the representation of low-income students by 30 percent without compromising their SAT or ACT test score standards.

“The kids can do it,” Levy said. “They’re just not getting a shot.”

Separate and Unequal

Poor students are overrepresented at community colleges, which tend to have tight budgets. And that equity gap is growing, causing experts like the Century Foundation’s Richard Kahlenberg to warn of increasingly separate and unequal institutions in higher education. Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, co-authored the new report with Jennifer Giancola, director of research for the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation.

The problem hasn’t gone unnoticed. Pressure has mounted on selective colleges to admit more low-income students -- and to help ensure that they graduate.

The Jack Kent Cooke Foundation is a longtime advocate on this issue. Since 2002 the foundation has funded the education of 891 undergraduates from low-income backgrounds who attended a competitive institution.

In recent years, the Obama administration, several advocacy groups and the news media have joined the cause and hammered selective colleges for catering to wealthy students. For example, a recent report from the Institute for Higher Education Policy identified selective colleges that enroll relatively small percentages of students who received Pell Grants.

The New York Times in 2014 published a report giving Vassar College top marks for enrolling students from low-income backgrounds. Vassar’s Pell Grant recipient percentage among first-year students climbed to 23 percent from 12 percent in 2007.

The Jack Kent Cooke Foundation later awarded a $1 million, no-strings-attached prize to Vassar for those efforts. The prize is to be an annual award for colleges that excel at enrolling and graduating low-income students.

Undermatching matters, the report said, in part because high-achieving students who are from low-income backgrounds are more likely to graduate if they attend a selective college. Their graduation gap with wealthier students increases at institutions with less competitive admissions criteria, according to research cited by the report. One reason for this is that wealthier colleges can afford to provide needed academic and other support to low-income students.

The stakes could get higher because the use of poverty preferences in admissions is a “viable alternative strategy to promote racial diversity on campus,” particularly if the Supreme Court limits race-conscious affirmative action, the report said.

“If we can’t do it by traditional affirmative action,” Levy said, “this is another route. And potentially a better route.”

In addition, the U.S. Congress is making noise about pushing wealthy colleges to spend more of their endowment money on financial aid. Even if the talk never becomes legislation, that pressure could influence colleges to do more for low-income students.

The foundation plans to send its report to presidents and deans of admissions at every highly selective college. Levy has spoken to governors in several states about the problem, and said he will expand on that outreach.

Levy said he has seen some movement on the issue, and that there is a willingness at some colleges to reexamine admissions policies. “These doors are not permanently closed,” he said.