You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

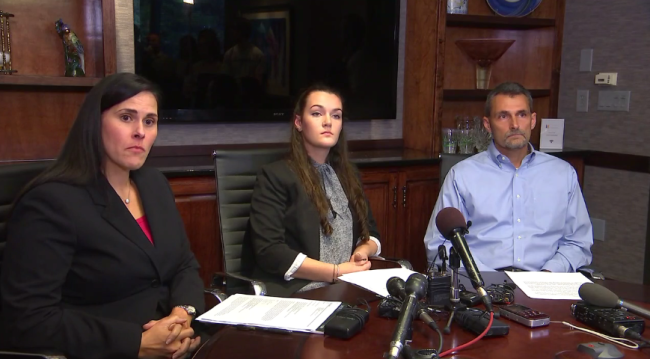

Delaney Robinson sits between her lawyer and her father during a news conference Tuesday.

ABC11

A University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill student says that UNC and its police department mishandled her report that she was raped by a football player, with campus police officers treating her like a suspect while offering the actual suspect support and reassurance.

“Rather than accusing him of anything, the investigators spoke to him with a tone of camaraderie,” the victim, Delaney Robinson, said in a statement Tuesday. “They even laughed with him when he told them how many girls’ phone numbers he had managed to get on the same night he raped me. They told him, ‘Don’t sweat it. Just keep on living your life and playing football.’ This man raped me and the police told him not to sweat it.”

The student’s allegations come at a time when colleges continue to face criticism from both victims and accused students that they are mishandling sexual assault allegations, following years of contentious federal intervention and pressure from advocates. Robinson is the third student in the last week to publicly call out an institution for botching a sexual assault investigation, with two students from the University of Richmond writing online essays accusing administrators there of mishandling their cases, as well.

Robinson, a sophomore at UNC, held a news conference Tuesday with her lawyer and her father. Robinson said UNC officials have dragged out the investigation into her allegations far longer than the 60-day time frame suggested by the U.S. Department of Education. Robinson’s lawyer, Denise Branch, said the university has continually extended the process while it waits on the results of the student’s rape kit to determine her blood alcohol content on the night of the rape, which Branch says is irrelevant to UNC's investigation.

Six months after Robinson first made the report to campus police, the accused student has not been arrested and there has been no administrative hearing. He remained on the football team.

During the university’s investigation, Robinson and her lawyer were able to view a recording of the athlete’s interview with the university’s Department of Public Safety, which has jurisdiction over the case. In the recording, they said, DPS officers comforted the football player. Their actions, Robinson said, stand in stark contrast to her own interview when she made her report to police.

Robinson said she was raped by the football player after a night of drinking on Valentine’s Day, and she reported the attack to police and submitted to a rape kit that same night. During Tuesday’s news conference, her lawyer shared a photograph taken at the hospital of Robinson with bruises on her neck.

“After I was raped, I went to the hospital and gave an account of what I could remember to the sexual assault nurse,” Robinson said. “Then I was again quizzed by DPS investigators, who consistently asked demeaning and accusatory questions. What was I wearing? What was I drinking? How much did I drink? What did I eat that day? Did I lead him on? Have I hooked up with him before? Do I often have one-night stands? Did I even say no? What is my sexual history? How many men have I slept with? I was treated like a suspect.”

In a statement Tuesday, the university said it could not comment on Robinson’s allegations, citing student privacy laws.

“The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is deeply committed to the safety and well-being of our students and takes all allegations about sexual violence or sexual misconduct extremely seriously,” Joel Curran, a UNC spokesman, said. “These matters are complex and often involve multiple agencies including law enforcement. While the university always tries to complete an investigation as quickly as possible, our priority is to ensure that the factual investigations are complete and conducted in a fair and thorough manner.”

Branch, Robinson’s lawyer, said that in early August, the Orange County district attorney’s office informed her that campus police had not found enough evidence to proceed with the case and that the office had decided not to charge the man. On Tuesday, James Woodall, the county’s DA, said the case was “investigated thoroughly” and hinted that charges may still be brought against the accused student.

Based on the August email, which said charges were unlikely, Robinson and her lawyer filed on Tuesday two warrants for the player’s arrest on charges of misdemeanor assault and sexual battery. The state of North Carolina allows victims of crimes to file their own warrants, if there's probable cause, but only for misdemeanors.

The player was suspended from the team on Tuesday, following the charges being filed against him by Robinson.

Branch said the university’s Department of Public Safety, which is a sworn police department, is not qualified to investigate crimes as serious as sexual assault, and that the department should hand such cases over to Chapel Hill police. She said that the investigation was botched from the beginning, with UNC officers first interviewing the suspect while one of his best friends, and a key witness in the case, remained in the room.

Later, Branch said, a Department of Public Safety officer argued that including Robinson’s rape kit in the investigation was unnecessary because the suspect claimed that the sex was consensual.

“Our position is that this police force is not capable of properly investigating a sexual assault case to an appropriate resolution,” Branch said. “There were so many missteps that took place.”

Robinson and Branch’s allegations are not the first time UNC and its Department of Public Safety have faced criticism over their handling of sexual assault reports. In 2013, a former UNC student told the student newspaper, the Daily Tar Heel, that after she reported an attempted gang rape by two UNC football players in 2010, she was told by UNC officers that the athletes “didn’t do anything wrong, and [she] should settle for an apology.”

The former student claimed the officers then worked with the players’ lawyers to craft a statement apologizing for the attempted assault. The student transferred to another university to avoid the players. At the time, the department denied pressuring the victim into not filing charges.

Sofie Karasek, director of education at the organization End Rape on Campus, said that law enforcement’s mishandling of sexual assault cases -- those involving athletes or otherwise -- goes beyond campus police departments. She pointed to the fact that 400,000 rape kits remain untested in the United States and to the recent much-criticized short sentence of a Stanford University student convicted of sexual assault as evidence of “the low priority that our law enforcement system places” on cases of rape.

“The criminal justice system is notoriously bad at prosecuting sexual violence cases,” Karasek said. “It's rare that a rapist will even be arrested, let alone prosecuted or convicted. And, many times, survivors experience revictimization from officers who blame the survivor for what happened to them or say that it's unlikely that charges will stick.”

UNC’s handling of sexual assault cases also came under fire in 2013, when the university’s student-run Honor Court charged a student with “disruptive or intimidating behavior” after she went public with her own rape allegations. The case ignited a firestorm of criticism against the university and its Honor Court and resulted in a still-ongoing federal investigation by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

Annie Clark, executive director of End Rape on Campus, was also among the then-current and former students who filed federal complaints against UNC in 2013, alleging that administrators had mishandled sexual assault reports. Clark was a subject of the critically acclaimed and controversial documentary The Hunting Ground.

"It’s incredibly disheartening that the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill seems to have mishandled yet another sexual assault case, especially while being under federal investigation for the same issue," Clark said. "Unfortunately, I’m not surprised. This case, while tragic, is unfortunately not an anomaly. It is yet another example of institutional betrayal and failure."