You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

While many states and cities are still working through the details and funding behind their attempts to create a free community college program, Tennessee has been busy expanding its scholarship.

The state was the first to create a free community college program. Now in its second year, the Tennessee Promise has led to student retention gains even as the number of participating students increases.

That success was highlighted recently by the state’s move to expand the Promise to include all adult residents through Tennessee Reconnect -- which already allowed adult residents to earn a certificate for free at any Tennessee college of applied technology. (The expanded program requires adults to not already have an associate or bachelor's degree, be a state resident for at least a year, apply for federal student aid, participate in an advising program and attend college at least part time.)

“One of the things we always heard was, ‘What are we doing with adults?’” said Mike Krause, executive director of the Tennessee Higher Education Commission. “And now we’ve been able to answer that question. We built a seamless message that is about everyone going to college.”

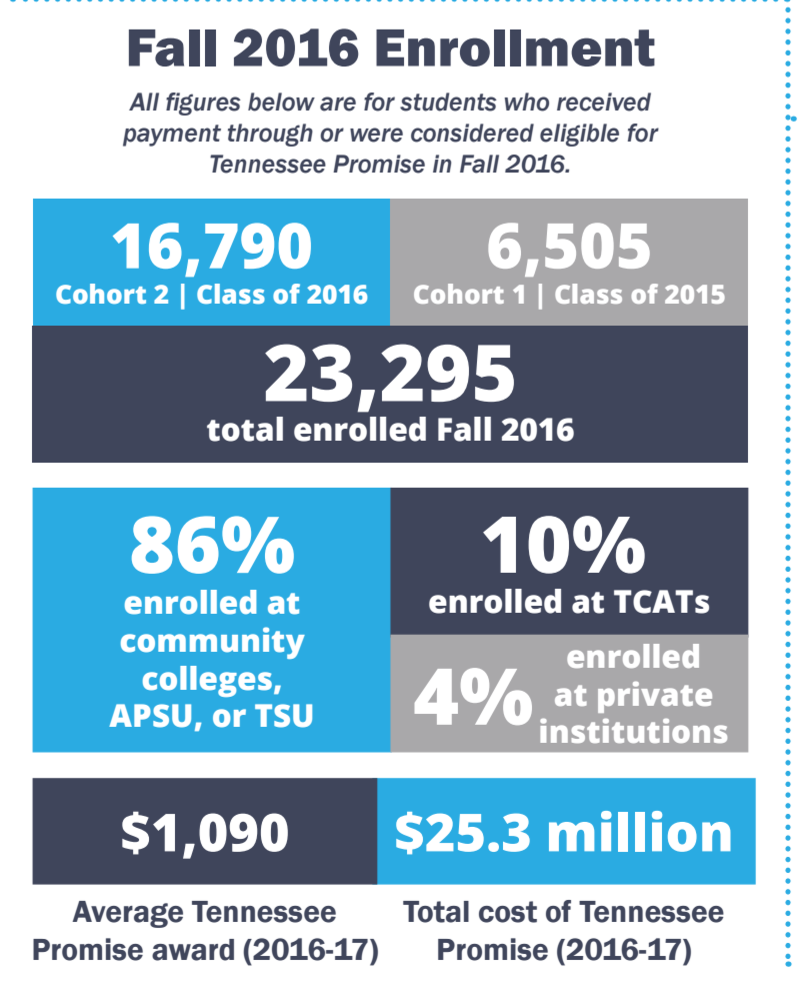

More than 33,000 students have received the Promise scholarship and enrolled in college since the program began in 2015, with nearly 23,300 enrolled in 2016.

But, as some states and cities are learning, replicating an initiative like the Tennessee Promise isn’t an exact science. And there are a few common barriers many programs have faced, including finances and politics.

“Money is the logical explanation,” said Laura Perna, director of the Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy at the University of Pennsylvania, who has examined more than 150 Promise programs to assemble a database of characteristics. “Many states have a number of programs spending a lot of money on different types of financial aid already. So it’s important for a state to consider the resources they have available.”

For instance, Oregon, which is using money from the state budget to fund its Promise initiative, allocated $10 million to the program last year. However, officials are estimating the cost will rise to $13.5 million as the state deals with a budget shortfall. Oregon has also seen some of its universities object to the Promise money, with some arguing for more funding for a state scholarship that benefits low-income students who attend public, four-year institutions.

Yet in Tennessee, the program's expansion is less controversial because it won’t directly cost taxpayers. The state is expecting the expansion to cost about $10 million a year, but those funds will come from lottery dollars. The main Promise program also is primarily funded from the state’s lottery reserves, which were placed in an endowment.

This year the total cost for the scholarship is $25.3 million.

“If you’re going to establish a program, you want it to be politically and financially sustainable,” Perna said. “Certainly we know from research that money matters, but it’s not the only thing that matters if you want to improve college attainment for underserved students.”

Where Oregon is facing a backlash from its four-year institutions, Tennessee allows public and private universities that offer an associate degree program to participate in the Promise program.

Four percent of Tennessee Promise students are enrolled at private institutions this year, with a 2 percent annual gain, according to the state higher education office.

“The compromise we made with the governor put us in a position where we would not oppose [the Promise],” said Claude Pressnell Jr., president of the Tennessee Independent Colleges & Universities Association. “We found, due to transfers and adult learners, our enrollment has gone up slightly over the past few years.”

While enrollment has increased at all the state's private institutions, Pressnell said three in particular have seen enrollment gains and the largest share of Tennessee Promise students: Cumberland University, Martin Methodist College and Carson-Newman University.

All three of those private institutions have recruited Promise students, either by agreeing to match the scholarship with institutional aid or by hosting Promise orientation sessions on their campuses, he said.

“I don’t think the other states know we do it,” Pressnell said. “It’s billed as a community college program, and they don’t realize that it’s portable to a four-year institution with an associate degree. Even in this state, it’s the least publicized piece of the program.”

Among the state’s four-year public universities, however, some institutions have taken an enrollment hit in recent years. At the University of Tennessee Martin, for instance, undergraduate enrollment is down 2.4 percent since last year, according to state data. The campus doesn’t offer associate degree programs.

However, UT Martin officials are more likely to praise the Promise program than blame it for low enrollment. After all, the university has seen a 14 percent decrease in enrollment over five years -- a trend that predates the Promise.

“We think the Tennessee Promise program is a good thing,” said Keith Carver, chancellor for UT Martin. “When you talk about a state trying to get 55 percent of its population to a postsecondary degree, whether it’s a technical certificate, an associate’s degree at one of the state’s community colleges or a four-year degree from one of our four-year colleges or universities, that’s a really good thing.”

Carver said it is reasonable to suspect that the Promise program has had some influence on the decrease in Martin’s undergraduate enrollment. But because the population was already in a decline, the reason for the change has been difficult to quantify.

UT Martin faces other issues that impact enrollment more -- an overall declining population in rural western Tennessee and high unemployment when compared to the rest of the state.

Instead, UT Martin is focusing its efforts on transfer students.

The campus is up 4.3 percent in Promise students who have transferred in, Carver said.

“As tough as our jobs are, in terms of dwindling pool of students, we’re having to work much more strategically,” he said.

Beyond the Money

Chris Baldwin, a senior director at Jobs for the Future, said as other states examine Tennessee and look at creating Promise programs, it’s important to note that the changes the state made weren’t decided overnight.

“What Tennessee has been able to do and the success they’ve had is broader than free community college,” he said. “For one, it fits the performance funding they’ve had for a long time. There’s a robust set of things they’ve done around developmental education and streamlining through guided pathways … I’d hesitate to say the success is purely about free tuition, so if you’re replicating it, it would mean you have to replicate a lot.”

Baldwin points to the Detroit Promise scholarship, which, while generating a lot of interest in community college, doesn’t solve the underlying problems students have, such as academic challenges and not having financial stability in their lives to sustain enrollment and be successful.

As New York pursues a free college program and other, similar Promise programs emerge across the country, the question will be what they are doing beyond free tuition, he said.

In Tennessee, officials feel their biggest impact hasn’t been financial but messaging. Perhaps that’s why Krause said he isn’t surprised other states haven’t exactly replicated the Tennessee model.

“It’s amazing to see more states haven’t realized by changing the messaging and leveraging financial aid … it takes time,” he said. “A lot of people are watching to see how it goes through a full cohort.”