You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

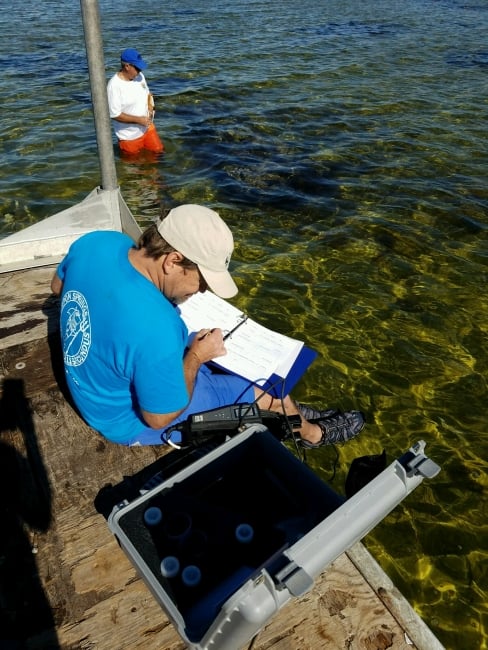

Staff of Sea Grant partner agencies collect water quality data at an oyster recruitment site.

Florida Sea Grant

Matt Parker, an aquaculture business specialist at Maryland Sea Grant, describes his work as free consulting for people who want to get into aquaculture, or farming of marine wildlife like fish or shellfish. That includes disseminating the latest research on best practices in oyster-growing operations -- an industry that has grown rapidly in the Chesapeake Bay area in recent years -- from the University of Maryland Extension to local businesses.

"It's the extension's job to relay the research in the university out to the industry," Parker said. "We're kind of like a conduit for research."

That kind of key assistance to local businesses could be imperiled by cuts to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration sought by the Trump administration. According to a budget memo obtained by The Washington Post, the White House is proposing to cut the budget of NOAA by 17 percent. Among the specified cuts in that document, the administration proposed eliminating the entire budget of the $73 million Sea Grant program -- a network of 33 college and university programs that tackle conservation and research programs, including the work of Parker and other extension agents with the Maryland oyster harvesting.

The memo, which came from the Office of Management and Budget, is part of the annual White House budget process. The executive branch directs agencies to draft budgets to submit to Congress based on White House priorities. The final numbers could change as administration officials and, later, Congress negotiate specifics. But the proposal to zero out Sea Grant’s funding suggests that the program may be fighting for its life.

Those who work with Sea Grant say it has fueled the growth in coastal regions of aquaculture industries that didn’t exist 20 or even 10 years ago. Scientists and businessmen alike compare the impact of the program on coastal businesses to that of land-grant universities in improving agricultural production in the U.S. While Sea Grant hasn't been around as long as the land-grant model -- the program just celebrated its 50th anniversary -- proponents said loss of that support would dramatic.

Sea Grant doesn’t just pay for lab-based campus research. It also funds educational outreach and work on practical problems faced by communities, often with the direct input of local businesses. Karl Havens, director of the Florida Sea Grant, said he believes Congress will save the program.

“It's an extremely practical program. Ninety-five percent of the money they appropriate goes directly to state programs. Only 5 percent stays in Washington,” he said. “What do we do with it? We solve problems that are identified by local businesses, residents and communities.”

Havens is in D.C. this week, along with the directors of other Sea Grant programs, for a national advisory board meeting. The trip was unrelated to reports of the proposed elimination of the program but provides those directors a timely opportunity to apprise lawmakers of the program's recent accomplishments in their districts.

State-level Sea Grant directors and their partners in academe and the business world say the work funded by the program is geared toward local environmental problems as well as industry needs -- all the while producing good science. John Weinstein, interim dean of the School of Science and Mathematics at The Citadel, said funding he and collaborators at Clemson University have received through Sea Grant has led to 12 presentations at national scientific conferences, two peer-reviewed publications and several community-based lectures to raise awareness of microplastic pollution.

“Because of this funding, we have made much progress towards a comprehensive understanding of the sources and fate of microplastics in the harbor, as well as the toxicological implications that microplastic exposure has on key species,” he said.

The talk of eliminating the program has local business owners as concerned as university-based researchers. Bob Rheault, executive director of the East Coast Shellfish Growers Association, said in a letter he sent to members of congressional appropriating committees that the proposed cuts to NOAA funding were "potential job killers."

"Our industry can be an engine of job growth in many ways, but many of these proposals will damage our ability to grow shellfish," Rheault wrote. "There are lots of measures we could take to create jobs (including regulatory reform), but stripping our national investment in marine science is not going to help."

Business leaders say if funding for research at university extensions is eliminated, that research won't be done by the private sector. Most aquaculture enterprises are small, family-owned companies, said Bill Sieling, executive director of the Chesapeake Bay Seafood Industry Association.

"They don't have the money or the resources to do that kind of research," he said.

In the shellfish and seafood industry, that work has involved improvements to sanitation, quality control, and the selection of the proper gear for harvesting shellfish like oysters.

"This is a win-win-win. There's no downside to this program," Sieling said. "It would really be a terrible blow to our industry -- not just in Maryland but in many other states."