You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

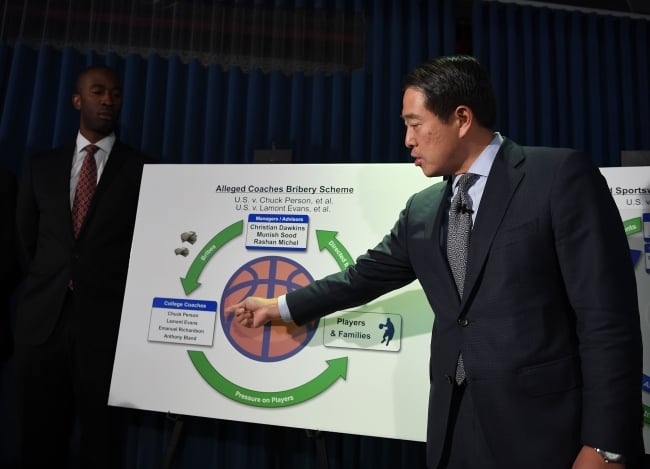

Acting U.S. Attorney Joon H. Kim announces the college basketball charges.

Getty Images

Scandals in big-time sports are like a Rorschach test separating believers and skeptics.

Whenever a major crisis hits -- a prominent football or basketball program gets whacked for breaking major National Collegiate Athletic Association rules, a university is ensnared in a cheating scandal involving athletes, athletes commit a rash of crimes -- a barrage of "I told you so" denunciations rain down from those for whom the scandal affirms their view that big-time college sports are corrupt and irredeemable. Many of the constituents of intercollegiate athletics, meanwhile -- coaches, NCAA officials and not a few college leaders -- patiently explain why the guilty party is an outlier or seek to differentiate it from their own program or institution.

And so the world keeps spinning.

Last week's announcement of federal charges of fraud and corruption against four college basketball coaches and a bevy of assorted agents, shoe-company executives and others would -- if the charges bear out -- arguably be the most expansive case of wrongdoing in the history of college sports.

By implicating six of the country's top 100 men's basketball programs in allegedly improper (if not illegal) payments to players, the Federal Bureau of Investigation charges would touch all but one of the Power Five sports conferences. (The impact could spread much farther if the FBI's call for tips starts a frenzy in which Adidas officials rat out their counterparts at Nike and Under Armour, or if the coaches facing jail time try to reduce their sentences by turning state's evidence against their peers at other institutions.)

Have these charges gotten the attention of presidents of the colleges and universities that play big-time sports? Are the new allegations making them look more closely at their own programs? And might they be less inclined than in the past to write off a scandal at another institution as an outlier and embrace the notion that a systemic problem exists in the NCAA's top tier?

It depends where you look. A day after the allegations were announced, Auburn University's new president, Steven Leath, told ESPN that while he was stunned by the charges, he gleaned from FBI officials "that they don't think there's some structural problem or some broader problem at the university, that this was an isolated individual … I don't think anybody else knew. I don't think there's any indication at Auburn that anybody else knew about this."

A series of interviews with current and former university presidents elicited a range of views.

F. King Alexander, president of the Louisiana State University System and chancellor of its Baton Rouge campus, which plays football and basketball in the powerhouse Southeastern Conference (alongside Auburn), said he was "asking questions just to make sure we’re not involved in any of this," he said. "Are we trying to find out if we have a problem? You're darned right; everybody should." LSU's teams sport Nike apparel, and Alexander said he took some heart from the fact that "we're not an Adidas school." But he acknowledged that might be small comfort. "Is Nike doing what Adidas did?"

(Nike and Adidas have been locked in a decades-long duel to associate themselves with universities and athletes who they believe can win the hearts of consumers everywhere, a competition that arguably got a lot more intense, and expensive, last year when Under Armour signed a $280 million deal with the Bruins of the University of California, Los Angeles.)

Susan Herbst, president of the University of Connecticut, said in an interview that with all the money and other incentives floating through college sports, "the conditions have been set up for this to happen -- a nice rich environment for the appearance of bad motives, impulses, bad apples to be up to no good."

But she expressed confidence that "we have nothing like that here." What reassures her? "I know the program thoroughly. I have an athletics director who is very hands-on, and I know the whole staff. Basketball isn't hard to know; they are very small, intimate programs, and it would be difficult to hide much in most of them … If your AD is paying attention, isn't on the road too much, I would think you would get a sense of whether [your program] could get wrapped up in this kind of thing."

Other presidents seemed more rattled by the turn of events.

Randy Woodson, president of North Carolina State University, which competes in the Atlantic Coast Conference with the University of Miami, another of the institutions singed in the FBI charges, said via email that he has "worked hard with my athletic director at NC State to insure that we have no knowledge of activities such as these here. I think it is a safe bet to assume that every university president is asking their AD and coaches hard questions about recruiting practices given the allegations outlined in this criminal investigation."

But "I can assure you," he said, "that I am not writing this off as a few bad actors. I'm worried that the alleged behavior that the FBI is investigating could be more widespread." The involvement of the FBI changes the equation, Woodson said, given that the government agency has subpoena powers that college sports' own governing body, and the institutions themselves, do not.

"NCAA investigations are one thing and we all take them seriously and work hard to play by the rules," Woodson said. "But when the investigative body has the power to arrest, compel testimony and ultimately convict, you can be assured that the truth will be discovered and likely very quickly."

Walter Harrison, who retired in July as president of the University of Hartford and spent 15 years in the NCAA's governance system on several of its most powerful committees, knows firsthand the difference between NCAA enforcement and federal law enforcement. As vice president for university relations and a key adviser to the president of the University of Michigan in the late 1990s, Harrison was among several officials tasked with investigating charges that members of the university's "Fab Five" basketball team had received payments to enroll there. "We were trying to figure out if any money had changed hands, and we tried to get to [former player] Chris Webber's bank accounts. They said no, and we couldn't go any further." The inquiry ended without major findings.

Not long after, Ed Martin, the booster at the center of the allegations, drew the attention of the U.S. attorney in Detroit for allegedly laundering money from an illegal gambling operation. "It turned out that hundreds of thousands of dollars had changed hands, and that five players had received money. Webber had perjured himself. But we couldn't touch it."

Even having seen the limits of what an internal investigation can uncover, Harrison said that if he were running a major basketball power right now, he would be "charging the AD to look very carefully … at which players you've been able to attract over the last few years, which [Amateur Athletic Union] coaches they were close to … what kinds of cars the kids were driving."

More fundamentally, Harrison said he was concerned that what one colleague a decade ago described as the "cesspool underneath men's basketball" -- money changing hands, corruption, stuff "you just don't want to know about," he was told -- is poised to be outed. "If I were leading the NCAA, I'd be thinking, 'If I don’t do something about this in a very visible way, Congress might,' and that would worry me a lot," he said. Harrison was referring to the re-emergence, spawned by the FBI investigation, of congressional interest that has, in the past, suggested a possible antitrust exemption to change how college sports are governed.

Harrison fears such an approach -- but John V. Lombardi thinks it might be the only meaningful solution.

Lombardi, who led the LSU system, the University of Florida and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst (and their powerhouse teams) during his decades as a university president, equates the alleged behavior of the basketball coaches implicated in the FBI inquiry to the lawbreaking employees at Wells Fargo, who "think they're promoting the interests of the institution or the company but really they're not."

It is wholly unsurprising that bad behavior is spilling out of a system with "so much money, ego, visibility and celebrity floating around," Lombardi said -- leaving "no question that we have to fix the systemic problem."

But most of his solutions for doing so -- "letting the kids go to the pros" without having to go through college, "allowing student athletes to commercialize certain aspects of their lives without becoming professionals" -- would require giving the NCAA (or another body) powers that only Congress can grant. "If you don't get this, the rest of the conversation is irrelevant," he said.

Lost in much of the hubbub surrounding the latest charges, Lombardi said, is the reality that in most major sports programs, "you've got 400-500 athletes, most of whom have no possibility of taking bribes," a reference to the male soccer players and runners, and pretty much every female athlete, and probably three-quarters or more of the football and men's basketball players who aren't destined for the pros.

"We've got to find a way to separate the money part from the student part," Lombardi said. If not, scandals like these might destroy the whole enterprise, the good with the bad.