You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Plans to restructure the University of Wisconsin System and merge many of its institutions are generating controversy, with the system’s president saying they are necessary, faculty members worrying they are being rushed and one expert likening the proposal to rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

But in a state university system constantly buffeted by budget pressures and political battles in recent years, some also hope that the latest in a long line of changes has the potential to help students, even if it is far from perfect -- or even fully formed.

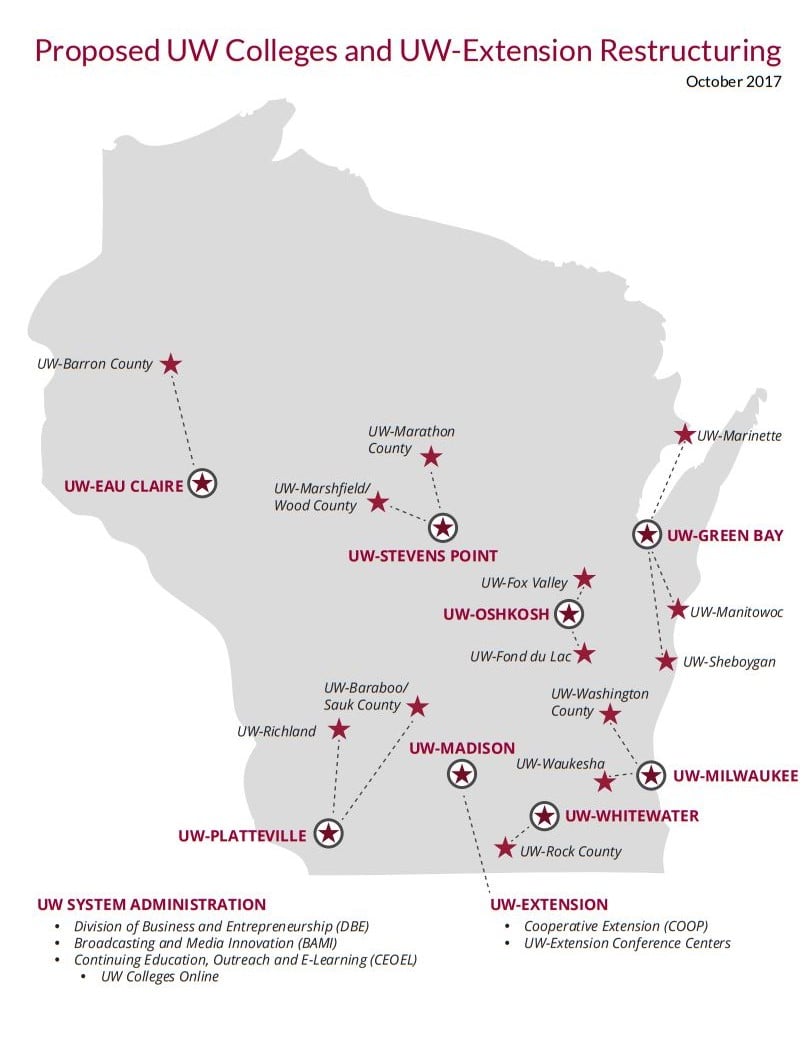

The UW System officially unveiled the planned changes Wednesday, shortly after they leaked to the press. The state’s two-year UW Colleges would be merged into four-year institutions in the same general geographic areas. Programs in the UW Extension would be moved to UW Madison and the system administration, and UW Colleges Online would move to the system administration.

The separate Wisconsin Technical College System would not be affected by the UW System proposal. Nonetheless, the plans stand out as among the most ambitious public system merger attempts seen in recent years.

While several states, like Pennsylvania, Vermont and Connecticut, have flirted with or pursued the idea of merging state institutions in recent years, systematic changes are virtually nonexistent. The best known example of mergers taking place is Georgia, where leaders pursued aggressive timelines but have launched consolidations in waves, only announcing a handful at any one time. That’s a stark contrast to the all-at-once approach being pursued in Wisconsin.

The changes are necessary because of a combination of budget pressures on higher education, demographic changes in Wisconsin and declining enrollment at UW’s two-year institutions, according to University of Wisconsin System leadership.

“We explored a lot of options, including just closing a few of them,” Ray Cross, UW System president, said in an interview. “The problem there is that these communities are so dependent on these campuses. So one of our premises was we must be able to find ways to maintain and preserve the university presence in these communities. It may not be as exhaustive as it was, but we need to find a way to do it.”

Merging the institutions is intended as a way to improve students’ access to college, Cross said. Some two-year campuses could add third and fourth years under programs at their new four-year affiliates. Students should find it easier to transfer to four-year programs.

The plan will go before the state Board of Regents in November for approval. Cross is proposing making the mergers effective July 1 of next year. But changes would stretch beyond that date.

“It will be a couple of years at least before we know where the fallout will be,” Cross said. “It will take a while to get there.”

The amount of money saved, changes in faculty numbers and changes to staff levels resulting from the restructuring have yet to be determined. But there will be budget savings, Cross said.

UW System leaders said that by 2040, population growth in the 18- to 64-year-old demographic -- a range of ages covering most students and workers -- is only expected to be 0.4 percent. At the same time, enrollment has been declining at the 13 different two-year UW colleges.

None of the colleges grew enrollment between 2010 and 2017. UW Rock County posted the smallest percentage decline, 28 percent, to 661.3 full-time-equivalent students. UW Manitowoc had the largest decline, 52 percent, to 250.7. Only one of the colleges, UW Waukesha, enrolled more than 1,000 full-time-equivalent students in 2017.

Faculty members at both two-year and four-year UW institutions worried that the process will be rushed. Some felt blindsided by a proposal they learned about mere weeks before it is set to go before the Board of Regents. They wondered about a tight timeline for implementing that plan.

“My primary concern is that the UW System administration is proposing such a sweeping overhaul without any stakeholder input, with very few details known and with very little time before the regents are supposed to vote on it,” said Nicholas Fleisher, an associate professor in the department of linguistics at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, via email. “This is the kind of major reorganization that is supposed to take years of careful planning, with appropriate feedback and approval from governance groups, in a transparent manner. What we're seeing right now is the opposite on all counts.”

Fleisher believes cost cutting is the administration’s only reason for pursuing the restructuring.

The new restructuring would come just a few years after a leadership consolidation at the two-year colleges driven by state budget cuts in 2015. The previous round of changes combined leadership positions for the 13 campuses into four regional leaders in an attempt to save money and cope with state budget cuts.

Meanwhile, some say that the talk of changing demographics misses a larger point about the population in Wisconsin. While projections show the number of traditional-age white college students declining, the number of nonwhite high school graduates is expected to grow in coming years.

“When you look at it, really, what’s the issue with enrollment?” said Noel Tomas Radomski, managing director of the Wisconsin Center for the Advancement of Postsecondary Education at UW Madison. “My hypothesis is that the colleges in particular that are close to the villages, towns and cities, they are not reaching out in different ways to first-generation white students, low-income whites, first-generation Hispanics, largely because they haven’t had to do that before.”

When the leadership centralization took place at the two-year colleges several years ago, many functions that used to be local were pushed up to regional or central offices, Radomski argues. That could hurt campuses’ ability to recruit local low-income and first-generation students.

Radomski believes the changes made in 2015 were poorly planned and implemented too quickly. Those mistakes are being repeated with the new plan, he said.

“We have a lot of youth who are graduating who, historically, they and their family haven’t gone to college,” Radomski said. “That is the real issue. We’re focusing on how we’re going to have branch campuses, and wham-bam, we’re going to have enrollment increases. My argument is we’re just moving chairs on the deck.”

Not only is the university system not recruiting appropriately for new types of students, but it is also not distributing enough state money to the colleges that need it most, Radomski argues. Still, he thinks the proposal has some potential.

Faculty members in leadership positions at institutions being merged took a nuanced view. Faculty at UW Green Bay were surprised, said Patricia Terry, a professor of engineering technology at the institution and chair of its University Committee, which functions as the executive committee for its Faculty Senate.

“None of us really knew this was coming down the pipeline until we heard about it yesterday,” Terry said. “There are some concerns about how the faculty at the now-satellite campuses are going to merge with the faculty at UW Green Bay.”

Professors at UW Green Bay have different responsibilities from their peers at the three campuses that will be merging into the institution, UW Manitowoc, UW Marinette and UW Sheboygan, Terry said. There are also different requirements for being hired as a faculty member at the various institutions.

Yet Terry believes the mergers could present opportunities once the kinks are worked out. They could allow UW Green Bay to grow its enrollment without stressing supporting resources, for example. If the curricula can be standardized between UW Green Bay and the two-year colleges being merged with it, students could be able to start at the two-year colleges, save money, and more easily transfer to UW Green Bay for their final two years with specialized courses.

Holly Hassel is a professor of English at UW Marathon County, a two-year college to be merged into UW Stevens Point. She is also the chair of the senate for faculty, academic staff and university staff at all UW Colleges, including UW Colleges Online.

“There’s a lot of confusion, a lot of concern,” Hassel said. “We’ve been in this structure of a single unified institution, the UW Colleges, for 40 years almost.”

Faculty members wonder whether the tenure they have earned will be honored in the merger, according to Hassel. The concern resonates in a state system where faculty members in recent years lost a bitter battle against changes they saw as weakening tenure protections.

But Hassel also mentioned optimism that the changes could benefit students. At some level, faculty may be exhausted from other fights and changes, like the battle over tenure and the UW Colleges administrative changes.

“I am actually surprised by the lack of faculty outrage,” Hassel said. “We’re kind of shell-shocked about it, but we’re going to try to keep it together because we have students who need us to. We’re trying to make it happen.”