You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Students at Cheyney University hear a lot of speculation these days.

“We might have to merge, or we might get shut down,” said Sharell Reddin, a junior at the historically black university about 20 miles west of Philadelphia. “We don’t like that idea at all.”

Merging would take away Cheyney’s integrity as the oldest historically black college or university in the country, said Reddin, 21, a business management major and president of the university’s Student Government Association. And she believes the rumors of consolidation are hurting Cheyney’s ability to recruit students for the future. That would be a critical blow to a deeply indebted public university whose enrollment has plunged over the last decade and that has been the center of legal battles, scandals and neglect.

Cheyney faces many issues, but its most immediate would seem to be with the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education. PASSHE loaned its smallest university $8 million in February to keep its doors open. The loan came on top of five other lines of credit provided over four years, bringing the total amount Cheyney owes the system to $30.5 million.

The state system’s Board of Governors this year also authorized a task force to design a new model for Cheyney. That model, to be built around the university’s Keystone Honors Academy, is supposed to put it on sound financial ground -- a tall task for a university with fewer than 1,000 students, an annual budget of about $30 million and massive debts even beyond what it has borrowed from PASSHE.

Cheyney’s crisis has been developing for years. The university’s supporters point to a history of underfunding from the state and unequal treatment that resulted in Pennsylvania being one of 10 states targeted by the federal government for operating openly discriminatory higher education systems. PASSHE signed an agreement with the U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights in 1999 to provide more funding for the university, but Cheyney's backers say the deal still has not been executed. They argue Pennsylvania owes Cheyney millions as a result.

Meanwhile, Cheyney’s accreditation is in danger over its finances and an unsettled leadership situation -- it has not had a permanent president since 2014. A dozen buildings on campus are not being used, Cheyney has the lowest four-year graduation rate in the state system, and it outsources most of its nonacademic functions. Additionally, it might have to pay back as much as $30 million in financial aid because of past errors.

In many ways, the crisis that has been unfolding at Cheyney is unique within the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education. Yet it is also reflective of -- and a contributor to -- a long series of events that have placed the system itself at a crossroads. The system of 14 state-owned universities was knitted together by law in 1983 and has in recent years become the center of increasing rumors as enrollment dropped, state funding slowed and Rust Belt demographic trends increased downward pressure on the system’s potential for a long-term recovery.

Enrollment across the system has dropped by more than 12 percent since a peak in 2010, plunging from 119,513 to 104,779. It has about 1,000 fewer permanent employees today than the 13,000 it had seven years ago. Officials project a $79 million funding shortfall next year. They’ve asked for additional state money to close some of the gap, but Pennsylvania’s Republican-controlled House of Representatives is likely to resist increasing spending, especially at a time when the state is facing a budget deficit of $3 billion through next summer.

| University |

Fall 2009 Enrollment |

2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloomsburg | 9,512 | 10,091 | 10,159 | 9,950 | 10,127 | 9,998 | 9,777 | 9,658 |

| California | 9,017 | 9,400 | 9,483 | 8,608 | 8,243 | 7,978 | 7,854 | 7,553 |

| Cheyney | 1,488 | 1,586 | 1,200 | 1,284 | 1,212 | 1,022 | 711 | 746 |

| Clarion | 7,346 | 7,315 | 6,991 | 6,520 | 6,080 | 5,712 | 5,368 | 5,224 |

| East Stroudsburg | 7,576 | 7,387 | 7,353 | 6,943 | 6,778 | 6,820 | 6,828 | 6,830 |

| Edinboro | 8,287 | 8,642 | 8,262 | 7,462 | 7,098 | 6,837 | 6,550 | 6,181 |

| Indiana | 14,638 | 15,126 | 15,132 | 15,379 | 14,728 | 14,369 | 13,775 | 12,853 |

| Kutztown | 10,634 | 10,707 | 10,283 | 9,804 | 9,513 | 9,218 | 9,000 | 8,513 |

| Lock Haven | 5,329 | 5,451 | 5,366 | 5,328 | 5,260 | 4,917 | 4,607 | 4,220 |

| Mansfield | 3,569 | 3,411 | 3,275 | 3,131 | 2,970 | 2,752 | 2,376 | 2,198 |

| Millersville | 8,427 | 8,729 | 8,725 | 8,368 | 8,279 | 8,047 | 7,988 | 7,927 |

| Shippensburg | 8,253 | 8,326 | 8,183 | 7,724 | 7,548 | 7,355 | 7,058 | 6,989 |

| Slippery Rock | 8,648 | 8,852 | 8,712 | 8,559 | 8,347 | 8,495 | 8,628 | 8,881 |

| West Chester | 14,211 | 14,490 | 15,100 | 15,411 | 15,845 | 16,086 | 16,606 | 17,006 |

| System total | 116,935 | 119,513 | 118,224 | 114,471 | 112,028 | 109,606 | 107,126 | 104,779 |

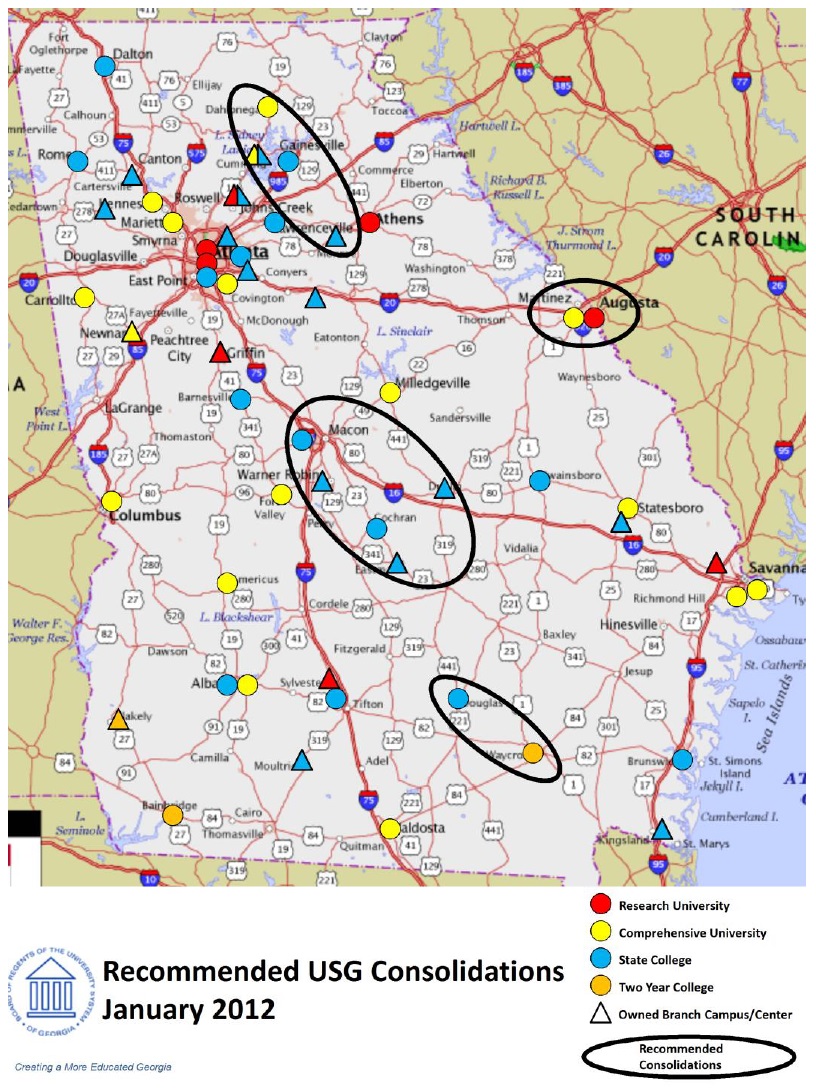

The situation would seem to be ripe for a massive realignment, perhaps including closures or mergers between institutions. Other states have attempted mergers that have saved money or better aligned their higher education systems with students -- most notably Georgia, which has lapped all other states with a five-round consolidation tear that has combined 14 institutions into seven since 2011 and currently has leaders attempting to fold four more into two institutions.

Behind the scenes, discussions of some sort of realignment within PASSHE have been rumored for years. But the situation is complex, even for the endlessly convoluted world of higher education. Cheyney is a prime example. It has long been whispered about as a takeover candidate by nearby West Chester University, the largest in the state system. Such a move would seem to make sense if you only look at the finances. But it would be highly charged and controversial because of the historical and racial ramifications. Governor Tom Wolf, a Democrat, has said he has no intention of allowing Cheyney to close.

Different barriers exist to eliminating other PASSHE universities that could be on the chopping block. PASSHE’s 14 universities and their handful of branch campuses are unevenly distributed across the state. While their graduation rates vary significantly, their proponents argue they provide critical services to otherwise underserved communities.

Additionally, the Pennsylvania system is heavily unionized, adding a chorus of voices to discussions about any changes. Plus, any major changes to PASSHE’s organizational makeup would need to be approved by the state Legislature. And local control is deeply embedded in Pennsylvania politics, meaning legislators and local interests will dig in to fight for the universities in their own backyards.

To complicate matters further, the system is not the only provider of public higher education in Pennsylvania. It operates separately from the state-related and better-known Pennsylvania State University, University of Pittsburgh, Temple University and Lincoln University, which receive some state funding but have more autonomy. Many have criticized Penn State for operating a network of campuses seen as competing with PASSHE institutions, a charge its leaders deny. PASSHE also does not include any of the community colleges operating in the state.

PASSHE campuses are marked by blue flags. Penn State campuses are represented by purple dots, University of Pittsburgh campuses by blue dots, Temple University campuses by red dots and Lincoln University campuses by green dots.

It all adds up to mean easy candidates for closure or mergers are nonexistent within PASSHE -- those in the worst financial situations tend to be in historically or geographically unique spots, making such moves difficult or impossible.

Georgia’s consolidation undertaking seems almost simple by comparison. Employees in the University System of Georgia are not unionized, and while the system is different from the Technical College System of Georgia and does not cover the Georgia Military College junior college, it still has more of a monopoly over public higher ed than PASSHE. In the 1970s it created some of the universities that were consolidated -- a stark contrast to PASSHE universities’ independent histories, some of which stretch back to the early 1800s. Further, Georgia does not exhibit the same political divisions as Pennsylvania, and system leaders did not need legislative approval to complete their consolidations.

In short, the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education is laced with tripwires for anyone trying to pull off mergers, affiliations or closures. Competition from a confusing web of higher education providers, high stakes for economically struggling regions, a deep-seated tradition of local governance and union power all threaten to derail a push for change. Further, Pennsylvania has not historically had a strong coordinating board like other states that would be able to rationalize what different institutions do. Pennsylvania leaders might be able to break the mold that has dominated for more than three decades. But it will not be easy, and it may take a degree of cooperation across the many higher education players that would be unprecedented in the state.

Tension at the Top

PASSHE’s recent history of difficulty and unclear way forward made significant Chancellor Frank Brogan's mention of the possibility of mergers or closures during his State of the System address in January.

“States are wrestling with the same issues we are, leading to the reorganization of public university systems in a number of states across the country -- including the merger or even closure of institutions,” Brogan said in his prepared remarks. “Is that where we are headed? That’s a question I can’t answer today, nor can anyone else.”

System officials have since sought to shift the focus away from mergers and acquisitions, emphasizing the fact that Brogan was referencing strategies other states have used. The point, they have said, is that all options are on the table as the system goes under strategic review. It has no preconceived notions of what the review will find. But Brogan has also since said that the state system “can’t just tinker around the edges.”

Labor leaders were surprised by the chancellor’s words, according to Kenneth M. Mash, president of the Association of Pennsylvania State College and University Faculties. The union represents roughly 5,500 faculty members and coaches at the 14 PASSHE institutions.

Mash said talk about cutting from PASSHE is like victim blaming. Systemwide enrollment is only down about 6,000 students from a decade ago, he said, arguing that the declines since 2010 are because that year was the peak of a bubble and that a long-term decline has not been playing out. Pennsylvania’s state appropriations per full-time equivalent student have fallen from a decade ago, he said.

| Year | State System Funding per FTE |

|---|---|

| 2007-08 | $4,776 |

| 2008-09 | $4,612 |

| 2009-10 | $4,135 |

| 2010-11 | $4,047 |

| 2011-12 | $3,761 |

| 2012-13 | $3,858 |

| 2013-14 | $3,902 |

| 2014-15 | $3,989 |

| 2015-16 | $4,052 |

| 2016-17 | $4,052 |

The union wants to focus on getting more public money for the system, Mash said.

“The chancellor’s comments were surprising to us in a way, because we thought we were doing a full-court press for more appropriations,” he said. “We have a real concern that we’re going to have a public higher education system that is dedicated to upper-middle- and upper-class folks. That, from what we understand, was not the purpose of having a public university system. It was meant to provide opportunities for upward mobility.”

Earlier this month, PASSHE hired the Colorado-based National Center for Higher Education Management Systems to conduct the strategic review across the system. NCHEMS, which has performed similar work in Colorado, Missouri, New Jersey, Oregon and Tennessee, will complete the effort in Pennsylvania this summer. It’s expected to look at issues of available resources, affordability and access.

The review will examine a number of different angles, said Patrick Kelly, NCHEMS vice president. It will do in-depth campus visits at PASSHE universities but will also compare the institutions to independent universities that are nearby as well as Penn State, Pitt and Temple.

“This is going to require action among many players in Pennsylvania: the Board of Governors, the Legislature, the governor’s office and the institutions,” Kelly said. “We will look at the other institutions in light of the overall state system, but that’s more from a data perspective.”

But it won’t be the first look at higher education in Pennsylvania. In 2012, then Governor Tom Corbett, a Republican, directed public and private university officials to study the 402 public, private and for-profit institutions in Pennsylvania. That study called for performance-based funding, containing costs and further studying consolidations, among other recommendations.

‘It’s a Crazy-Quilt System’

Interviews with current and former leaders in the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education and its universities make clear that the idea of consolidations has loomed heavy behind the scenes for years. Kenneth M. Jarin (below) is a former member of the PASSHE Board of Governors who served as chair for six years starting in 2005. He described conversations about consolidation as informal, arguing that the universities were doing well during his tenure, which coincided with high enrollments.

“Imagine, for a moment, if we would have said in 2011 or 2010 when we were doing really well and our numbers were up and funding was decent, if we would have said, ‘OK, we need to change the whole system and start consolidating schools and closing schools or changing the nature of schools,’” he said. “We would not have had a snowball’s chance in hell of getting anybody to take us seriously.”

Even so, Jarin isn’t blind to the challenges the state system faced or faces today. PASSHE has always kept its tuition significantly below levels charged by the state-related universities. But it still faces competition, he said.

Even so, Jarin isn’t blind to the challenges the state system faced or faces today. PASSHE has always kept its tuition significantly below levels charged by the state-related universities. But it still faces competition, he said.

For the 2016-17 academic year, PASSHE set its tuition at $7,238 for an in-state student. Penn State tuition, by contrast, was $17,900 for residents attending the institution’s main campus and between $13,296 and $14,828 at its Commonwealth Campuses, which are spread throughout much of the state (and are often criticized for competing with PASSHE institutions).

| Year | PASSHE In-State Tuition |

|---|---|

| 2007-08 | $5,177 |

| 2008-09 | $5,358 |

| 2009-10 | $5,554 |

| 2010-11 | $5,804 |

| 2011-12 | $6,240 |

| 2012-13 | $6,428 |

| 2013-14 | $6,622 |

| 2014-15 | $6,820 |

| 2015-16 | $7,060 |

| 2016-17 | $7,238 |

Meanwhile, closing or changing PASSHE institutions is incredibly painful, because they serve as economic centers for many regions of the state, Jarin said. Some parts of the state that have a PASSHE campus have few other employers -- let alone sources of employment providing high-paying union jobs.

“It’s a crazy-quilt system,” Jarin said. “The reality is there should be a comprehensive look at the community college system, the state system and the Penn State system. And something different should come out of it.”

But discussions about financial problems tended to talk around the issue or resulted in revisions to the system’s state funding formula that effectively took funds away from solvent institutions and redirected them toward those in financial trouble, Weisenstein said in an email. That bought time but did not fix the underlying problems. Within the last few years, talks started to include topics like institutional restructuring, mergers and, to a lesser extent, closures.

Leaders have also referenced the difficulty of bringing everyone to the table in a decentralized system. PASSHE’s Board of Governors is made up of politically appointed members. Individual universities’ trustees tend to be alumni or local leaders. Then there are the politicians with interest, and the university presidents themselves.

“In the past, there also seemed to be a tendency to solve problems through a system or centralized approach that assumed the reasons for the current financial situation were similarly shared across all institutions and, therefore, the solutions should be systemwide,” Weisenstein said. “In fact, this is true in such cases as underfunding or financial obligations imposed by collective bargaining, but other reasons for financial success or woes may differ across institutors.”

Universities Try to Chart Their Own Path Forward

As PASSHE leaders have been talking, many university presidents have been trying to chart paths forward -- with varying success. At Cheyney, interim President Frank G. Pogue claimed that uncertainty about the future has not hurt student interest in enrolling. Undergraduate applications for the fall are up by 30 percent over the same time last year, and numbers of students accepted are up by 15 percent, he said in an emailed statement Friday.

“As I type this response, I am preparing to welcome several hundred high school students who are touring campus today,” he said. “There continues to be the recognition that this 180-year-old historic university, the oldest HBCU in America, provides a high-quality education.”

Elsewhere in the state, Karen Whitney (left) has been the president of Clarion University -- just off of Interstate 80 in Pennsylvania’s rural northwest -- since 2010. Clarion’s enrollment during that time has fallen from 7,315 to 5,224.

Elsewhere in the state, Karen Whitney (left) has been the president of Clarion University -- just off of Interstate 80 in Pennsylvania’s rural northwest -- since 2010. Clarion’s enrollment during that time has fallen from 7,315 to 5,224.

But Whitney said the university is shifting its focus from a one-size-fits-all university of the 1980s to a university concentrating on professional programs in demand today. The former normal school continues to have strong teaching programs, and it is expanding its undergraduate and graduate business offerings as well as programs in health and human services.

Today, 80 percent of Clarion’s students are in professional programs, and Whitney believes such a focus will help the university grow. It draws from a 200-mile radius that stretches into Erie, Pittsburgh and central Pennsylvania, as well as Akron and Cleveland in Ohio, she said.

“I don’t need a review,” she said of the PASSHE strategic review. “But I welcome the information.”

A three-hour drive to the northeast, Mansfield University has been attempting to differentiate itself as well, according to Jonathan Rothermel, an associate professor of political science and the University Senate president. Outside of Cheyney, Mansfield is the university most often mentioned as a candidate for closure or consolidation. Its enrollment is the second lowest in the PASSHE system at just 2,198. It sits on the side of a hill in Pennsylvania’s sparsely populated Tioga County.

On March 21 Mansfield notified its faculty members that layoffs may be in store at the end of the 2017-18 academic year. It delivered a letter to the faculty union saying that academic programs might be affected, but it did not specify which programs. In doing so, Mansfield became the first university in the PASSHE system to open the possibility of faculty layoffs this year, although system officials said more could follow.

Faculty members indicated they would try to move forward despite the uncertainty. Mansfield’s faculty was not particularly rattled by the PASSHE strategic review when it was announced, Rothermel said. He had previously been put on a retrenchment list tagging him for a possible layoff amid a budget crunch in 2013, along with about 25 others. He was eventually taken off that list but believes the experience served as a wake-up call that Mansfield had to change.

The university is trying to define itself as Pennsylvania’s premier public liberal arts institution, Rothermel said. It joined the Council of Public Liberal Arts Colleges, becoming the only institution in Pennsylvania to do so. Faculty members have been working hard to recruit students directly.

The city of Mansfield lacks a community college, so discussions often mention that the university could add two-year programs or be turned into a community college. The hydrofracking-fueled Marcellus Shale boom brought a jolt of money into northern Pennsylvania as energy companies moved in to extract natural gas from the ground. As one former education official who declined to be named said, right now you can drive a truck in many parts of the state, but those jobs will not stay forever.

Rothermel, however, voiced skepticism about changing the university into a feeder campus. That would likely mean denying students the chance to take courses on campus in subjects like philosophy, some sciences, music or even history, he said. Whittling down course offerings means taking away options for local students and forcing them to travel if they want a full college experience.

As for merging, one of the PASSHE universities closest to Mansfield is Bloomsburg University, about 90 miles away. Mansfield already shares back-end services with Bloomsburg. But the institutions have separate identities and strong alumni bases, Rothermel said.

“People are very, very proud of where they came from,” he said, going on to reference Mansfield’s Mountie mascot and Bloomsburg’s Husky mascot. “Once a Mountie, always a Mountie. How does that square with becoming part Husky and part Mountie? It would be difficult.”

What Can Be Done?

It would be difficult, but not impossible. Matt Baker (below left) is a Republican in Pennsylvania’s House of Representatives. Mansfield is in his district. He is also a member of the PASSHE Board of Governors.

If Mansfield has to create a two-year program to build its enrollment to viable levels, it’s worth considering, Baker said. He’d be open to other out-of-the-box options, too, like Penn State affiliating with Mansfield. The only thing Baker would rule out is closing the university. It’s the fifth-largest employer in Tioga County, employing more than 400 people, he said.

If Mansfield has to create a two-year program to build its enrollment to viable levels, it’s worth considering, Baker said. He’d be open to other out-of-the-box options, too, like Penn State affiliating with Mansfield. The only thing Baker would rule out is closing the university. It’s the fifth-largest employer in Tioga County, employing more than 400 people, he said.

“The biggest significant issue is getting the enrollment figures back up so the university is self-sustaining,” Baker said. “They’re nearly out of reserves, as are, quite frankly, four or five other universities.”

Baker is clear about the pressures mounting on the PASSHE universities. Many of the PASSHE universities’ financial constraints are set by the system’s administration, which determines tuition and negotiates labor contracts. Without higher state appropriations, universities can only raise revenue through other means, like donations or housing fees. But the system has been very conservative in its treatment of tuition, keeping rates low. At the same time, costs are growing.

The state system reached a new contract with the striking Association of Pennsylvania State College and University Faculties last year. The contract was negotiated centrally, but costs are passed on to individual universities. PASSHE or legislators do not have to make up for increased costs under union contracts. That worries Baker.

“You compound it all with this new contract for the unions, and you don’t know how you’re going to pay for it going forward over the next three years -- $75 million in additional costs,” Baker said.

“I guess, at this point, as is true in a lot of policy concerns in the Legislature, sometimes it takes a crisis or near-critical mass in order to start having these serious conversations,” he said. “We are at that point now.”

The president of Bloomsburg University, David Soltz, expects universities to start picking up more back-office operations for one another. In the next year, Bloomsburg will likely be doing all of Mansfield’s human resources operations, he said.

Soltz is retiring at the end of the academic year, but he expects to see some regionalization and differentiation among PASSHE universities over the next several years. Some universities might offer too many programs, and more shared programs could be possible through growth in online courses.

Full-campus mergers will be harder, Soltz said. He cited a late winter storm in the middle of March that dropped 22 inches of snow on his campus. It would be hard to put a merger in place that effectively tells students and faculty members they need to travel through the teeth of Pennsylvania’s mountains when winter storms are possible.

Soltz agreed with Baker’s sentiment that closing campuses is a line not to be crossed.

“I don’t think any university president would say they want his or her university to close,” Soltz said. “Neither would the regional trustees. There is clearly a line.”

The Difference in Georgia

Pennsylvania’s recent experience and history could hardly be more different from that in Georgia. Where Pennsylvania has danced around the idea of institutional consolidation, Georgia dove right in. Where Pennsylvania’s public higher education institutions are a disparate patchwork, the University System of Georgia includes two-year colleges with a few thousand students and the flagship University of Georgia, with more than 34,000 undergraduates.

The University System of Georgia has finalized the consolidation of 14 institutions into seven since former chancellor Hank Huckaby (below) started a merger push in 2011. Its Board of Regents recently approved another pair of consolidations, which will combine Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College with Bainbridge State College and combine Georgia Southern University with Armstrong State University.

Huckaby’s role shouldn’t be overlooked when analyzing Georgia’s success finalizing consolidations. He came to the chancellor position with a long political history that gave him a deep knowledge of the state, its Republican politics and the university system. He had directed the governor’s planning and budget office, been commissioner of the Georgia Department of Community Affairs, and led the Georgia Residential Finance Authority. He’d been a teacher and administrator in the university system. He’d been a GOP state representative.

Huckaby’s role shouldn’t be overlooked when analyzing Georgia’s success finalizing consolidations. He came to the chancellor position with a long political history that gave him a deep knowledge of the state, its Republican politics and the university system. He had directed the governor’s planning and budget office, been commissioner of the Georgia Department of Community Affairs, and led the Georgia Residential Finance Authority. He’d been a teacher and administrator in the university system. He’d been a GOP state representative.

Huckaby recommended consolidating eight Georgia institutions into four in October 2011. That November regents adopted a set of consolidation principles used to evaluate other potential consolidations -- they would be assessed on whether they increased opportunity, improved accessibility, avoided duplication, created opportunities for economies of scale, boosted regional economic development and streamlined administrative services. Since then, regents have approved and finalized several additional rounds of consolidations.

The university system had created several two-year colleges in the mid-20th century. The idea behind many of the consolidations was to try to create a modern university system rather than one crafted four decades ago, said Shelley C. Nickel, executive vice chancellor for strategy and fiscal affairs at the university system, who has led consolidation work since it started in 2011.

The university system had created several two-year colleges in the mid-20th century. The idea behind many of the consolidations was to try to create a modern university system rather than one crafted four decades ago, said Shelley C. Nickel, executive vice chancellor for strategy and fiscal affairs at the university system, who has led consolidation work since it started in 2011.

“We were finding that we have a number of colleges in the southern part of our state that were two-year colleges developed in the ’60s and ’70s,” she said. “We no longer have growth there. We don’t have the high school graduates that we had during those boom years.”

Three of the system’s four initial consolidations involved institutions established in or after 1964. The remaining consolidation took the 3,000-student Georgia Health Sciences University, established in 1828, and combined it with the 6,700-student Augusta State University, established in 1925.

Since then, Georgia has combined institutions of various size and type. But it’s possible to pick out some trends. The system has often consolidated institutions in the same region that could be seen as complementary but not alike, often merging two-year institutions into four-year institutions. Those institutions are also often connected by student transfer patterns -- when the two-year Georgia Perimeter College was combined with the doctoral-granting Georgia State University in a move finalized in 2016, it became part of an institution that was already the top transfer destination for its students.

The system also often merged institutions where a president was retiring or had recently departed, creating less of a possibility for tension among university leaders.

“We had all kinds of different scenarios with presidents,” Nickel said. “Some had announced their retirement. Others were interims already. And then we had two standing presidents where one was not going to be the president of a new university. When we did -- and I think the board did this correctly -- after we named the consolidations, the board announced who the new president was going to be, so there was no question about who was going to be the lead president for the implementation.”

Still, no formula exists for which institutions will fit together, according to Nickel. She listed different types of combinations -- the merger of Georgia Health Sciences University and Augusta State, which created what is now Augusta University, develops science, technology, engineering and math programming. Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College and Bainbridge State College were recently approved for consolidation despite the fact that they are about 80 miles apart -- they’re similar because they are both agriculturally driven.

No physical campuses have closed in Georgia because of the consolidation spurt. Regardless, state legislators have often asked tough questions, Nickel said. Local residents have had difficult conversations with leaders after consolidations are announced.

Not closing campuses means leaders have not milked the consolidations for all the cost savings that could theoretically be available. Even so, the University System of Georgia estimates the consolidations have led to a collective $24.4 million in savings that can be redirected to education.

The lack of campus closures has led some skeptics to label Georgia’s actions administrative mergers instead of institutional consolidations. Nickel rejected that, saying she believes they are driven by academics. Academic offerings rose from eight bachelor’s degrees to more than 20 after Gainesville State College was combined with North Georgia College and State University to create the University of North Georgia, she said.

The Georgia system is free of many constraints complicating potential PASSHE mergers -- it is not unionized, nor has it needed lawmakers’ approval for any of the changes it has made.

As a result, Nickel can’t counsel other leaders on navigating unions or the legislative approval process. She said she’s talked to education leaders in other states who are interested in learning how Georgia executed its consolidations. But she declined to share the names of those states.

There is no blueprint that is guaranteed to work, she said.

“We’re making sausage,” Nickel said. “Every one of them is different and has their own culture.”

Even when leaders overcome the massive challenge of finding institutions they want to consolidate, a long list of challenges still remain. Jennifer H. Stephens, the deputy chief of staff at Georgia Gwinnett College, saw those challenges up close. She was a fellow with the American Council on Education and observed the consolidation between Georgia State and Georgia Perimeter that was finalized last year.

“Everything had to be done,” she said. “Let’s make sure we have our registration process that’s going to allow all these students to come in. And then you would have things that would pop up in terms of fees charged here and there, and are we going to keep them separate and think about creating a similar fee structure? All of those issues had to be worked through.”

What to Expect

Only time will tell whether PASSHE will go down the road of consolidation -- or change substantially at all.

Weisenstein, the former West Chester president, can see the potential for several future outcomes. PASSHE institutions might find ways to reinvent themselves as more relevant to more students. They could make significant changes to their missions, cut programs that are not in demand and convince holdout constituencies that change is necessary. Some other experts have suggested a similar possibility built around the idea that PASSHE is currently focused almost entirely on students who just graduated from high school and could build a new student base around adult education.

But the current PASSHE strategic review could also simply buy more time for leaders to kick the can down the road. That could mean mounting financial challenges erupting into a greater crisis. Or leaders could encounter harsh resistance.

“The other scenario is that recommendations resulting from the study will indeed suggest that institutional mergers are necessary or Pennsylvania has too many institutions and some need to be closed,” Weisenstein said. “These recommendations will most likely start the political battles that could rage on for a very long time while failing institutions begin to close their doors to students.”

In the past, if Penn State and PASSHE had any kind of relationship, it was often seen more as competitors than collaborators. But there may be some reason for optimism. Penn State President Eric Barron has a pre-existing relationship with PASSHE Chancellor Brogan. He was president at Florida State University for a short time when Brogan was chancellor of Florida’s university system.

Still, Brogan has been calling for discussions across Pennsylvania’s higher education sectors since he arrived in the state almost four years ago, according to PASSHE spokesman Kenn Marshall. None have taken place yet.

It's also worth noting that Pennsylvania and Georgia are not alone in looking at consolidations.

“Pennsylvania is part of a larger challenge with changing demographics in the Northeast and parts of the Rust Belt,” said Thomas Harnisch, director of state relations at the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. “The problems are particularly acute in rural regions of the state.”

Other Northeastern states, such as Vermont, are pursuing merger strategies to save money. The State University of New York System several years ago backed off from consolidating presidents at several of its institutions after legislators balked. Some presidents held the position at two universities for a time, but SUNY ultimately reverted to one president for one campus.

The point of the SUNY effort was to keep campuses standing alone but give them the financial benefits of shared back-office services, Chancellor Nancy Zimpher said. She said she learned just how important local politics can be from the experience. She still believes the institutions’ identities were going to be preserved, though.

It’s difficult to pull off any type of merger without a mandate from a governor or Legislature, Zimpher said. Today she still sees a problem with too much institutional infrastructure and said she would pursue a similar effort in the future if she’d first spoken with enough state and local leaders.

“Frankly, I would try it again, because it is fair to say I learned a lot, and I still think we can be more efficient,” said Zimpher, who plans to step down from SUNY this year. “I think it’s very possible that once we sort of get the programmatic road map for SUNY in a year’s time, we might be ready to try it again.”

Current politics in New York could make that a moot point, however. Governor Andrew Cuomo has proposed a tuition-free public college plan that could drastically alter the financial landscape for the SUNY system. Even if the plan, which the state’s private colleges have fiercely resisted, is not implemented, it demonstrates a different appetite for public higher education support in New York than in Pennsylvania.

Ultimately, the question in Pennsylvania seems to be when the speculation finally ends and the changes begin.

“Something has to change,” said Soltz, the president of Bloomsburg University. “Because if something doesn’t change, I think some of my sister universities, my colleagues' universities, are going to fail.”