You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

University of Texas Longhorn Band

Should outnumbered men feel uncomfortable on college campuses?

That’s a highly charged question hanging over Texas after remarks last week by the state’s commissioner of higher education. The commissioner, Raymund Paredes, commented before Thanksgiving on the fact that some campuses in Texas have student bodies that are 60 percent women and 40 percent men.

“We’ve been told by some presidents that we’re getting to the point where males feel uncomfortable on college campuses, on some college campuses,” Paredes said.

To many, the comments, made at a University of Houston Board of Regents meeting and first reported in the Houston Chronicle, came off as tone-deaf in light of the broader discussion currently taking place about gender, abuse and power dynamics in higher education and society. Within higher ed alone, recent headlines have centered on allegations that professors holding positions of power sexually harassed or preyed upon women. Some critics also point out that women are underrepresented in top jobs at universities and that they do not earn equal wages to men in the workplace. That's not to mention other aspects of campus atmosphere that hardly seem to indicate women holding all the power -- the fact that the higher education institution most revered by many in Texas is football, and that fraternities play a powerful role in the social life of many campuses.

Against that backdrop, it can be argued that women are the ones with cause to feel uncomfortable on college campuses -- not men.

Paredes says, however, that his comments have merit when taken in context. He had been speaking about the issue of enrolling and graduating male students from minority groups, an area where colleges and universities in the diverse -- and quickly further diversifying -- state of Texas have struggled. When Paredes spoke about men feeling uncomfortable, he had just said the state was behind in graduating African-American and Latino men. Texas has a lot of work ahead of it to bring up participation among economically disadvantaged groups, he said.

Paredes declined during a telephone interview last week to share which college presidents have told him men are feeling uncomfortable on their campuses. But he reiterated that he was referring to groups of students that are financially at risk or less prepared for college than others.

Paredes declined during a telephone interview last week to share which college presidents have told him men are feeling uncomfortable on their campuses. But he reiterated that he was referring to groups of students that are financially at risk or less prepared for college than others.

“They are obviously going to feel uncomfortable if they don’t see many people like themselves on a university campus,” Paredes said. “I didn’t mean to suggest that we were at a crisis point, but I meant to suggest that a lot of people think we’re getting there.”

Asked more specifically about whether white men are also feeling uncomfortable, Paredes said that white male participation and completion rates are lower than rates for white women.

“We have a challenge in terms of the participation of males,” he said. “I think most of us want to have participation at levels that mirror their presence in the overall population, and I think most of us would be very concerned if any group -- African-American, Latino, white -- if their participation rates in any important societal function were much lower than their actual presence in the overall population.”

Yet experts question whether equal participation rates in higher education should be the goal in a world where men overwhelmingly hold top positions and earn more at work, on average, than women. Even accepting that goal, some questioned whether men’s comfort is the right focal point. Some pointed out that college campuses are places to challenge students -- places where, by definition, students should feel uncomfortable when confronted by issues like changing gender roles, economic prospects and patriarchy.

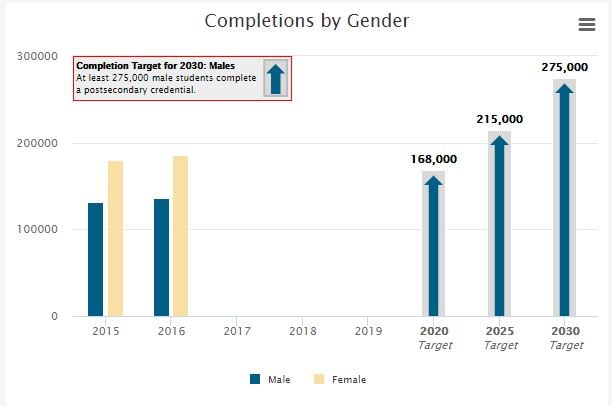

It’s important to note, though, that Paredes made the argument in Texas, where the state’s higher education strategic plan sets specific goals for degree completion by 2030. The top goal is to have at least 60 percent of young adults aged 25-34 holding a postsecondary credential of some sort by that year. But the plan also sets specific benchmarks for future certificate or degree completion among several groups of students: Hispanic students, African-American students, economically disadvantaged students -- and male students.

The plan describes the goal for men as a way to “monitor progress toward gender parity.”

Some retort that gender parity or gender equity can’t be measured solely by the number of students enrolled and the number of degrees granted.

“We should be cheering that more women are completing higher education, but they are still being dealt a fairly unlevel playing field,” said Anne Hedgepeth, interim vice president of public policy and government relations at the American Association of University Women. “Look not just at student populations but also at who is teaching classes, who is in higher ed administration, who are the provosts and on the boards that control higher education. Who is in political power, governors especially?”

The governor of Texas and the state’s top legislative leaders are all men. So are 121 of 150 members of the state House of Representatives and 23 of 31 members of the state Senate. Men make up a significant majority on a list of public university leaders kept by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

That’s not the situation only in Texas. By and large, power structures with the most influence on colleges and universities remain predominantly male, Hedgepeth said.

AAUW has also found that women working full-time across the country earn only 80 cents on the dollar compared to their male counterparts. In Texas, they only earn 79 cents on the dollar.

Men in Texas carry comparatively less debt then women upon graduating. Student loan debt as a percentage of first-year wages for students graduating with four-year degrees totaled 67 percent for men and 77 percent for women, according to the Texas Higher Education Almanac. For those graduating with two-year degrees, it totaled 34 percent for men and 42 percent for women.

Other statistics show men lagging when it comes to degree completion. Men are less likely than women to graduate from high school, enroll in higher education or receive a higher education degree.

Men are roughly half of the Texas population. But men were only 43.6 percent of the state’s 1.65 million students enrolled in higher education in 2016. They represent about 42 percent of the state’s degree completions.

The gender breakdown on Texas campuses varies significantly. Some campuses, including main campuses for Texas A&M and Texas Tech, enroll more male undergraduates than women. Others skew far in the other direction.

Even with that complex set of data, some worry about the nuanced views that could be lost in the rush for gender parity.

“I’m just concerned that some of the complexity is getting flattened out of the picture,” said Susan Heinzelman, director of the Center for Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. “It irks me so much, because I think of the university as a place where complexity is nourished and celebrated. If that’s getting flattened here, good luck with the rest of the culture.”

Heinzelman was one of several experts who agreed that the debate about men feeling comfortable on campus depends on which men are being discussed. Students from historically underrepresented populations who feel uncomfortable could be seeing many universities as white, elitist, unfriendly places. Men studying subjects like engineering, where they dominate in number, but feeling uncomfortable about the number of women on campus, would be a different question.

At some level, the issues involved should make students with advantages feel uncomfortable, Heinzelman said.

“I’m all in favor of making people uncomfortable,” she said. “Not threatened -- but calling attention to the world in which they live and have privilege.”

It’s also worth pointing out that male enrollment varies drastically between Texas universities and individual programs. Texas Tech University, with an undergraduate student body that is 55 percent men, has run a one-day conference intended to help young girls find careers in science, technology, engineering and math. UT Austin, with a 47 percent male undergraduate enrollment, has an initiative called Project MALES, which works with Latino and black men.

Project MALES has male and female college students serving as mentors for boys in Austin-area schools and middle schools, said its coordinator, Mike Gutierrez. About 60 undergraduates and 10 graduate students work with 120 middle school and high school students.

Many of the participants in the program feel cultural influences or pressure to earn money instead of attending college for several years, Gutierrez said. Gender gaps on campus can be noticeable for students enrolled in college when they are in class or walking around campus. But the program tries to provide a place for discussion about that issue and other issues, like sexual assault.

“We try to give a little bit of time and space for them to kind of describe any concerns they might have,” Gutierrez said. “A lot of times, we want to make sure these young men can talk about what it means to be a male student on campus.”

Other institutions in Texas have programs for some men as well. At Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Sam Houston Establishing Leadership In and Through Education attempts to boost academic, professional and personal development among Hispanic and African-American men. It works with about 160 students and wants to grow to at least 200, said Miguel Arellano Arriaga, program coordinator. The men who take part don’t necessarily feel outnumbered on campus, he said. But women would like access to a similar program.

“We do get a lot of women who ask why there isn’t a program like this for them,” he said.

Outside Texas, many found it hard to believe that men feel uncomfortable on campus. That was the initial reaction of Jerlando F. L. Jackson, director and chief research scientist at Wisconsin’s Equity and Inclusion Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin Madison. But his thoughts changed as he considered the different populations of men and the ways young men might interpret the things they see unfolding on campus around them.

Men might feel uncomfortable if they see programs and initiatives for others but don’t think they have access to those programs, he said. They might feel uncomfortable if they think they need to overanalyze every move in their relationships with women.

“My thought over all changed in thinking through this,” Jackson said. “If we did unpack this current collegiate experience, there are probably many more topics, and matters that call males to question what their role is on a college campus.”

While many may believe the historical advantages or power dynamics men enjoy should be changed, the idea of special programs to help men navigate college is more controversial. After all, it can be argued that many of higher education’s existing power structures function as boys' clubs or support systems for men.

Jim Shelley is the manager of the Men’s Resource Center at Lakeland Community College in Ohio, one of only a few programs of its kind. He hears from students, administrators and faculty members across the country. Broadly speaking, he believes there is a lack of interest in helping men on college campuses.

“The typical attitude is men are the problem and need to be reprogrammed,” he said. “What we’re trying to do with the program is kind of rephrase that to state that men have problems, too.”

It’s a hard discussion for administrators to have without minimizing the challenges women face. The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board recognizes higher ed needs to address serious problems related to gender, Paredes said. He called for addressing those problems with data.

“We know we are not going to achieve our goals -- 60 percent of our youngest cohort of adults having some form of postsecondary credential by 2030 -- if we don’t have heavy levels of participation by all groups,” he said. “And that’s what the message is.”