You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Speakers at academic seminars are the voices and faces of their fields, whether they like it or not. So it’s important that those voices and faces reflect who’s actually working in a given discipline. A new study says that colloquiums continue to fall short on that front, at least in terms of gender.

The study, published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that some 3,652 colloquium speakers at 50 selective institutions in 2013-14 were more likely to be men than women, even when controlling for rank and representation of men and women in the disciplines that sponsored the events -- the factors often cited to explain gender imbalances in academe.

“There are implications all over, but one of reasons we wanted to do this study is we’re profoundly interested in the idea of gatekeepers -- people who, by virtue of their positions, have the ability to keep members of certain groups from achieving their full potential,” Michelle Hebl, study co-author and Martha and Henry Malcolm Lovett Professor of Psychology and professor of management at Rice University, said Monday. “They may do this unwittingly or not, but this is one of those situations where gatekeeper bias has some real consequences, since it’s very important to give these colloquium talks. It’s a really great way to build your network and showcases your research and your credibility.”

Christine Nittrouer, lead author and one of Hebl’s graduate students, said colloquium remarks sometimes serve as pseudo-job talks that lead to job offers or other professional opportunities. Yet the processes governing speaker invitations are far less formal than job searches and therefore less likely to include what Nittrouer called egalitarian protections.

“When we’re not cognizant of these things, our subtle biases can creep in in subtle ways,” she said.

Beyond gender and rank of available speakers, the researchers also investigated whether female and male faculty members at top universities valued speaking engagements differently or turned them down at different rates. They found no significant evidence of either hypothesis, though women did nominally value speaking engagements more than men did.

The authors did find, however, that female colloquium chairs made a big difference in women being selected as speakers: female chairs chose women 49 percent of the time, on average. Male chairs, meanwhile, chose women as speakers 30 percent of the time.

Big Implications

Hebl said the study’s implications extend beyond colloquiums, to other major kinds of career-impacting decisions. The answer isn’t rushing to put women on the "holiday party committee," since they’re already overrepresented in service roles, she said. But it may be important to put them -- in bigger numbers -- on truly important committees to share their input as gatekeepers.

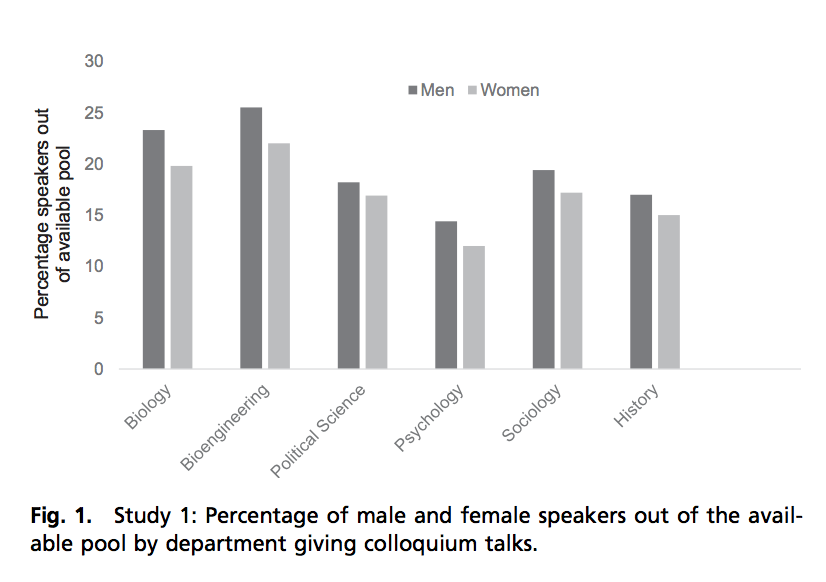

For their study, Nittrouer, Hebl and their co-authors created a database from all the featured colloquium speakers on departmental websites of the top 50 U.S. universities, as ranked by U.S. News & World Report. In an attempt to represent the main divisions or colleges at the institutions with neither overly small nor overly large shares of women, they focused on the following disciplines: biology, bioengineering, political science, history, psychology and sociology. Those fields range from 22 percent to 47 percent female, according to the study. To establish an available speaker pool, they created a list of professors from those departments in the top 100 institutions, according to U.S. News & World Report.

The researchers also emailed a subset of faculty members to determine whether giving colloquium talks was significantly more important to men and women, and whether men reported declining invitations to talk significantly less frequently than women did. They also called administrators of each of the 300 programs studied to identify the gender of the colloquium chair or gender composition of the colloquium committee, to see who was making decisions about speakers.

Results

Men gave more than twice as many colloquium talks over all (69 percent, or 2,519) as did women (31 percent, or 1,133). Although full professors gave the most colloquium talks (1,781), many associate professors (989) did as well. Some 882 assistant professors also gave talks. In an advanced analysis controlling for rank and program, the effect of gender was highly significant. Men were still 1.2 times more likely than women to speak at colloquia.

Finding no evidence of women’s self-selection out of talks, the researchers moved on to their “gatekeeper” data. Regarding who selects speakers, they found that about one-third of speakers were selected by an individual and two-thirds were selected by committee. Of their sample of colloquium chairs, 11 were women and 23 were male. Female chairs sponsored talks in which 49 percent of speakers were women. Male chairs sponsored talks in which 30 percent of speakers were women. Colloquium committees that had a greater percentage of women on them were marginally more likely to have a higher percentage of female colloquium speakers -- meaning that, at least in a group setting, both men and women may exhibit bias against women speakers.

Amber E. Boydstun, associate professor of political science and chancellor’s fellow at the University of California, Davis, said the new paper’s findings are directly in line with research on implicit bias. In this case, she said, bias means that when people -- both men and women -- organize colloquiums, they’re more likely to think about and therefore ask male scholars than female ones.

“Add to that implicit bias the fact that scholarly networks tend to be dominated by men, and it makes perfect (if unfortunate) sense that women -- and women of color especially -- would be underrepresented as colloquium speakers,” she added via email.

Boydstun co-authored a paper earlier this year on political science’s Women Also Know Stuff movement to increase representation of women and their research in disciplinary discussions, decisions and events. One of the project’s key recommendations is that academics involve women in colloquiums and other conferences.

Featuring only or mostly men in colloquiums gives the “impression that women are not doing important work,” Boydstun and her co-authors wrote. “By disproportionately inviting men to give talks, we unnecessarily diminish the profiles of our women colleagues.” Womenalsoknowstuff.com includes a list of more than 1,300 female political scientists for reference for putting together syllabi, conferences and more.

The new paper calls for further study across disciplines not surveyed. But other research suggests such findings would likely be parallel. A 2014 study regarding large microbiology conferences, for example, found that the inclusion of even one woman on "convener" teams had a major impact on who gets to speak: about 25 percent of the speakers invited by all-male teams were women, compared to about 43 percent of the speakers invited by teams with at least one female member. Organizing teams with at least one woman were also much less likely than all-male organizing teams (9 percent versus 30 percent) to produce symposia in which all panel members were men.

Nittrouer and Hebl co-wrote their study with Rachel Trump-Steele, another graduate student at Rice, and David Lane, an associate professor of psychology, statistics and management on campus. They were joined by Leslie Ashburn-Nardo, an associate professor of applied social and organizational psychology at Indiana University-Purdue University in Indianapolis, and Virginia Valian, distinguished professor of psychology at Hunter College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.