You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Modern Language Association

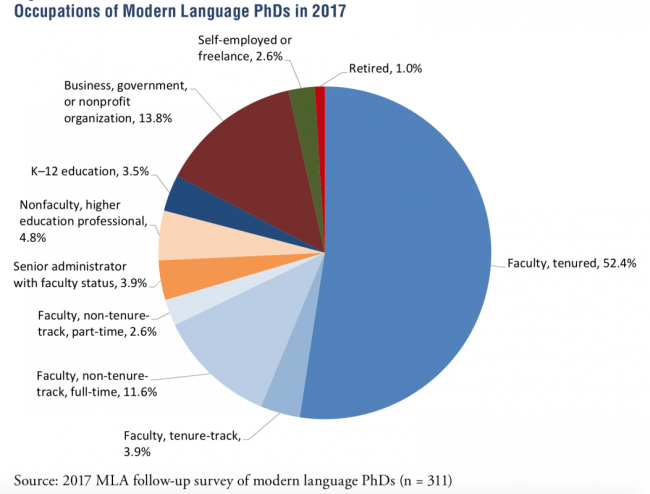

Most English and modern language Ph.D.s are working in academe, and 52 percent hold tenured faculty positions, according to a new, limited study of their career outcomes from the Modern Language Association.

Even so, the variety of job paths these Ph.D.s pursue outside higher education is notable and should inspire further efforts to track graduates’ career trajectories, the association says.

Last summer, MLA researchers contacted 1,949 Ph.D.s who were included in a related 2015 study of doctoral recipients from 1996 to 2010, asking them to complete a jobs survey. The response rate was low, which MLA’s new report acknowledges -- just 310 graduates, or 15 percent of the original sample. One additional, more recent graduate was included this time, for a total of 311 Ph.D.s.

The "small number of respondents reminds us how enormously far tracking efforts have to go before the profession can claim to have anything approaching a comprehensive picture of the occupations and employment histories of the tens of thousands of living individuals who hold doctoral degrees in English and other modern languages," MLA says. But the 311 respondents did provide "a set of suggestive illustrations that should spur the further research needed to gather information that will confirm or correct the findings presented here."

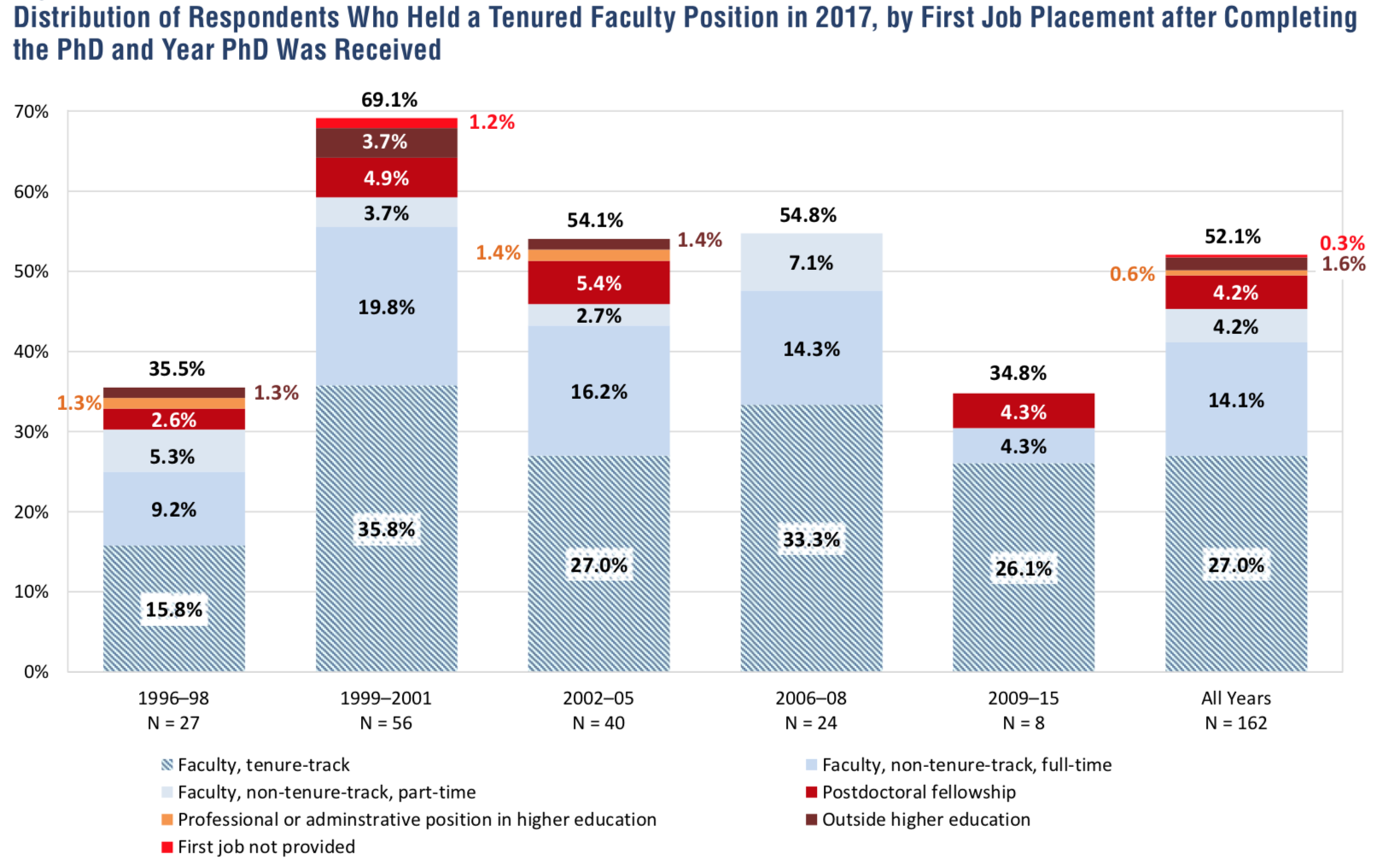

From the Mouths of Ph.D.s

The vast majority of respondents -- 79 percent -- said they worked in academe. Over all, 52 percent of survey respondents said they held a tenured faculty position. That’s higher than some might expect, given the dismal tenure-track job market. But MLA notes that having a tenured position varied by when respondents earned their Ph.D.s, specifically whether the tenure-track job market was booming or busting at the time. Just 36 percent of those who received their Ph.D.s from 1996 to 1998 worked in tenured positions when surveyed last summer, compared to 69 percent of the 1999-2001 cohort, for example. And just 35 percent of the 2009-15 cohort was tenured by 2017.

Data on first jobs upon completing the Ph.D. tell a similar story. About 45 percent of graduates from 2006 to 2008, when the tenure-track job market in the humanities was relatively good, landed tenure-track faculty jobs right out of graduate school. That figure fell to 26 percent after the Great Recession, in 2009-15.

Just about 4 percent of the overall sample held tenure-track, nontenured positions at the time of the survey, while 12 percent and 3 percent said they worked in full- and part-time faculty positions off the tenure track, respectively. About 9 percent worked in administration.

Some 21 percent worked outside academe. Fourteen percent worked in business, government or nonprofit organizations. A 4 percent sliver worked in K-12 education, while 3 percent were self-employed. One percent was retired.

“Of course, the future may bring more movement from non-tenure-track to tenure-track positions for those in this most recently graduated cohort, as it has for three of its four predecessors,” David Laurence, MLA researcher, wrote in a separate, partial analysis of the report. “Or the future may confirm a more permanent shift to non-tenure-track appointments and to employment outside academe -- a shift that is apparent in the data for the 2009-15 cohort to date and that characterizes the experience reflected in the far lower fraction of graduates in tenured and tenure-track positions in the 1996-98 group and the markedly higher 29 percent who have moved out of academe into self-employment or business, government, and nonprofit organizations.”

The most “urgent message” of these data may be “how important it is for both doctoral programs and their students to remain open and active in consideration of the fullest possible range of employment options and opportunities, especially perhaps if a leading one of those options is the career of a tenured faculty member,” Laurence added.

Maybe You Can Get Satisfaction … but We Still Need More Data

MLA’s full report also provides data on job satisfaction among humanities Ph.D.s. In relatively good news, 77 percent of respondents reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their work. Those levels varied somewhat with when students graduated, too: those who earned their Ph.D.s since the recession were the largest share of “neutral” satisfaction respondents.

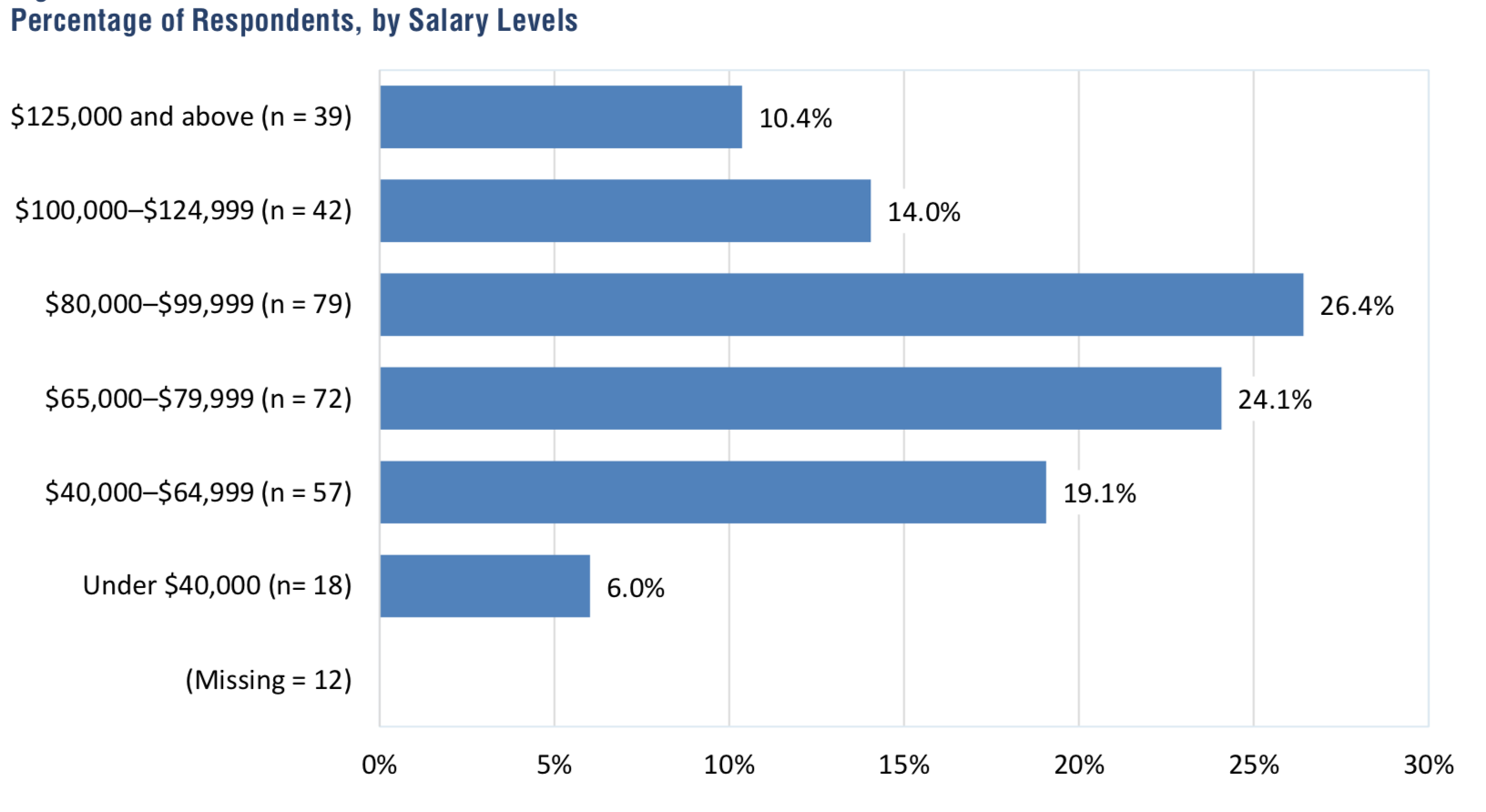

There's some data on earnings, too. About 50 percent of modern language Ph.D.s are earning between $65,000 and $100,000 annually.

Humanities Ph.D.s haven’t been included in the federal Survey of Doctoral Recipients since 1995. So what humanities Ph.D.s do with their degrees has been a giant question mark, at least on a national level, since then. Recent years have seen a major push for institutions and professional societies to help close that data gap and track humanities Ph.D.s, however, so that students know what kinds of careers to plan for -- especially given the shrinking faculty job market -- and so that graduate programs know how to help them.

These data collection efforts are not easy, and they’re less than comprehensive. But the MLA study provides crucial insight into what humanities Ph.D.s are doing, and even if they like doing it.

Paula Krebs, executive director of the MLA, said Wednesday that while the sample size “is way too small to be very specific,” the available data suggest “that we urgently need a more comprehensive picture of the occupations and employment histories of Ph.D. recipients in our fields.” MLA hopes that the “preliminary snapshot will prompt further research and tracking, especially at the departmental level,” she said.

Still, Krebs said that graduates’ career variety already demonstrates “how important it is for doctoral programs and graduate students to be aware of the full range of employment options for humanities Ph.D.s.” With graduates working in diverse jobs already, she said, doctoral programs that track their graduates make it easier for current students to “imagine and pursue” their own paths.

Robert B. Townsend, director of the Washington office of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, said the small response rate to the survey was indeed a concern. That noted, the results “seem quite valuable for the discussion about career diversity for humanities Ph.D.s,” he said. Specifically, Townsend said the report underscores what he’s noticed in helping prepare similar studies for the American Historical Association, where he once worked, and the academy: how diverse even individual career trajectories can be after the Ph.D.

“When I talk to audiences about these issues, that diversity of career trajectories can be very hard to convey,” he said. “This report provides tangible evidence for those conversations and provides some provisional numbers that help us move beyond personal anecdotes. I think it will be very helpful.” Among other things, Townsend said, the data suggest “how hard it is to make it onto the tenure track after you start down one of the other paths.”

Likening such studies to “taking a snapshot of a moving object,” Townsend said he learned while helping write a 2013 AHA report on Ph.D. career outcomes that, for instance, some respondents clearly had moved on to other jobs by the time he went back to double-check the data.

While career outcomes and trajectories are surely the flashier part of this report, Townsend said he was also struck by MLA’s findings on job satisfaction. A recent academy report found that Ph.D.s working inside academe were significantly more satisfied over all than their counterparts outside academe, but there is no such divide in MLA’s sample.

Townsend said he assumed part of the difference is that MLA’s survey population consists disproportionately of young people, “whose struggles to find a secure position are amply documented elsewhere in the report.”

Once again, he said, “it points to the value of looking at the results as potentially changing over time.”

Suzanne Ortega, president of the Council of Graduate Schools, said in an emailed statement that MLA's and AHA's recent studies "are filling big gaps in our understanding of the careers of humanities Ph.D.s."