You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

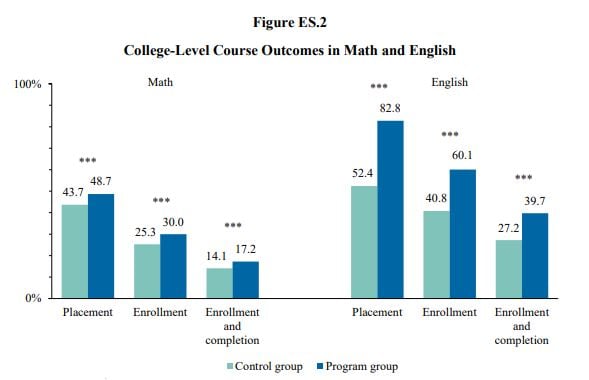

New research shows more community college students pass college-level courses in math and English when multiple measures are used to determine their placement rather than relying solely on a single placement exam.

The report from the Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Readiness at Columbia University's Teachers College found that when colleges use multiple measurements, such as grade point averages, the placement of students into college-level math instead of developmental courses increased by five percentage points. That increase was more than 30 percentage points for college-level English.

Students who placed into these college-level courses were also more likely to pass them in their first semester compared to remedial students. In the college-level courses, students could receive additional support to help them pass. Meanwhile, it may take remedial students an additional semester or two before they can enroll in the college-level course.

“We’ve got enough evidence now for people to move in the direction of using multiple measurements,” said Elisabeth Barnett, the lead researcher on the project from the Community College Research Center and a co-author of the report. “One thing becoming clearer is that high school GPA is an especially good measurement.”

The researchers followed 13,000 students at seven State University of New York community colleges who took courses in 2016 and 2017. At SUNY colleges, the College Board’s Accuplacer exam is used to determine placement. Students in the study were either assigned placement using Accuplacer or were placed using alternative measurements such as high school GPA, performance on state exams or high school class rank.

Preliminary results for about 5,000 of those students show that 14 percent were placed higher with multiple measurements than they would have been with a single assessment, while 7 percent placed lower. In English, 41.5 percent of students were placed in a higher-level course and 6.5 percent placed lower.

The use of multiple measurem for placement also had an impact on course completion. Students were 3.1 percentage points more likely to enroll in and complete a college-level math course in the first semester after being placed with multiple measurements compared to those who were placed with a single assessment. In English, students were 12.5 percentage points more likely to enroll in and complete the college-level course.

The research also found impacts related to gender and racial equity. More women than men were placed in the higher college-level math course under multiple measurements, while black and Hispanic students benefited more than their white peers with placement in college-level English.

“What we’re learning is that it’s hard to capture what students have the potential to do with a single test,” Barnett said. “There are so many factors that determine whether and why students will be successful in a course, and high school GPA is capturing noncognitive factors like, did they turn in an assignment? Did they show up? Did they follow through?”

While the CAPR study will continue to evaluate the performance of these students for more semesters, Barnett said the body of research has been clear that using a single placement exam does not work.

Placement Changes in California

A few states and college systems have in recent years enacted policies that require institutions to use multiple measurements. A survey earlier this year found that in 2016, 57 percent of two-year colleges used this approach for math placement, compared to 27 percent in 2011. North Carolina’s community college system, for example, has been using multiple measurements for placement. Last year, California passed a bill requiring the state’s 114 community colleges to begin using multiple measurements for placement in corequisite remediation courses by next year. Corequisite is the popular form of remediation that places students in college-level courses but gives them additional support.

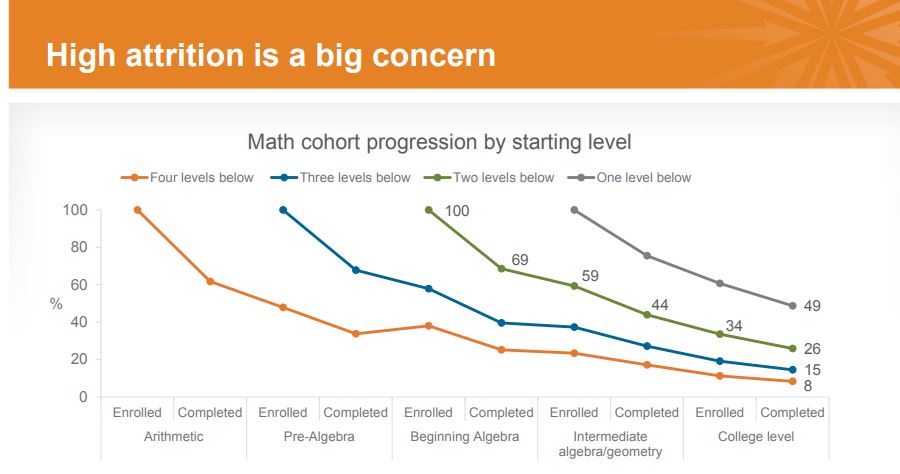

The Public Policy Institute of California found that a large number of students never took or completed college-level courses when a single placement exam put them in traditional remedial courses.

For example, of the students who placed four levels below college-level courses in remedial math, only 8 percent eventually completed the college-level courses.

"It’s pretty appalling and compelling data that students in many cases were starting not just one level below, but two or three or four levels below college level,” said Hans Johnson, senior policy fellow and Higher Education Center director at PPIC. “But strikingly, the share of students who made it out of remediation was much lower. When we’re talking remediation in this lesser system, it would be a year at best for students placed two levels below to reach a college-level course.”

Although a few of California’s two-year colleges started using multiple measurements years ago, there are still many that are starting this system or revamping remediation courses to comply with the law. And some colleges are not looking to make any changes, said Katie Hern, an English instructor at Chabot College and the co-founder and executive director of the California Acceleration Project, which has been helping colleges make the remedial changes.

“Some colleges are very ready and some are looking for loopholes,” she said. “I know colleagues at other institutions who believe this kind of change will undermine the quality of student learning; they fear teachers may dumb down the curriculum, they mistrust the data and there is this disbelief that comes from their pre-existing understanding of what is good for students.”

Geoff Hagopian, a professor of math and computer science at College of the Desert, said he’s opposed to the changes because they eliminate the basic skills curriculum for new students and populate college-level courses with students who are not ready. The idea that students will pass college-level courses because they were placed closer to that course is false, he said.

“The California Community Colleges have managed to compress into three or four semesters of remediation a process that often entails unlearning bad algorithms and reformulating poor study habits: an amazing feat, if you can pull it off,” Hagopian said in an email. “To expect that these same students are going to be more successful … without remediation is disingenuous and cynical.”

Hagopian fears that the state’s new outcomes-based funding formula, which will reward the colleges for student completions of college-level math and English, will lead to more instructors passing underprepared students in the college-level courses instead of placing them in remediation.

Hern said the financial implications of these changes in California are still unknown, because of the new performance funding metrics and because each college will differ in how they implement the changes or reallocate resources.

However, the move to multiple measurements does come with costs for some colleges. In New York, for example, the CAPR study found that across five of the SUNY colleges, building the alternative placement system added $110 per student to the current cost of using a single placement exam. Ongoing costs averaged about $40 per student.

Barnett said the next area to study will be the cost-benefit analysis of using multiple measurements to determine if it’s worth the extra expense colleges incur.