You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

For years City College of San Francisco faced declining enrollments as it weathered budget shortfalls, an accreditation crisis and leadership turnover.

It was a positive development when enrollment at the two-year college finally began climbing last year. But it still wasn't enough to stop CCSF administrators from moving forward with a plan to eliminate a third of nearly 1,200 credit courses over the next seven years to help balance the college's budget. College officials are also planning to increase the number of high-demand classes offered, such as accounting, math and English, as part of that process. Administrators aren't certain how many more courses will be added, however.

“We are decreasing offerings of some underenrolled classes but also increasing the offerings of in-demand classes,” said Connie Chan, media relations director for the college. “We’re looking into the future and we are staying on track.”

Last month, Chancellor Mark Rocha proposed cutting about 400 underenrolled classes over several years. Those classes, ranging from labor relations to ethnic studies, are multiple sections of general education courses that have had fewer than 20 students enrolled in the last six years, according to CCSF data.

Rocha wasn’t available for comment, but he told board members in December that the underenrolled “courses over a period of time have to go or else the college cost structure will just be unsustainable.”

Those cuts could also help lower an $11 million budget deficit City College is facing this year. CCSF has a $185 million operating budget, but last year was the first time the community college didn’t receive about $35 million in stability funding from the state. That funding had been given to help City College make up the shortfall from the loss of enrollment revenue precipitated by students' uncertainty about CCSF's accreditation status. The enrollment decline began immediately after the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges sanctioned the college for financial and administrative problems. At the time, City College had been running budget deficits for several years and had dipped into its reserves to cover shortfalls. The sanction led to a years-long dispute between the college and the accrediting commission.

“We no longer have that large number of full-time-equivalent students,” said Brigitte Davilla, a City College board trustee and a faculty member at San Francisco State University. “But we're growing. We’re trying to keep in mind our budget is much less without stabilization funds.”

City College earned back its full accreditation in 2017 after years of uncertainty. But rebuilding hasn’t been easy.

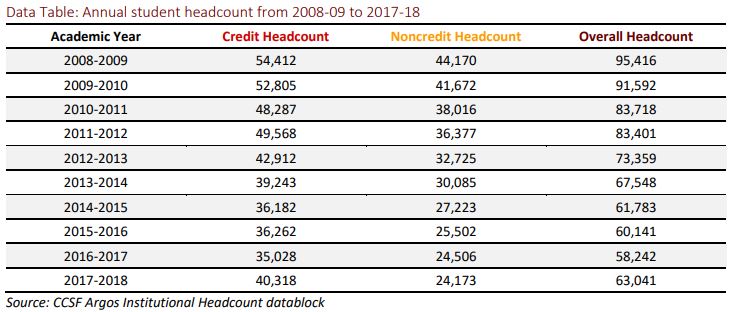

When the accreditation crisis occurred in 2012, the overall student head count at City College fell by 12 percent, going from about 83,400 in 2011 to 73,359. Enrollment reached its lowest level in 2016, when just 58,242 students were attending the college, but the number rose to 63,041 students in 2017, the first increase in 10 years.

Enrollment at City College has rebounded in part because of the Free City College program started by the college and the City of San Francisco. The pilot program allows city residents to attend the college tuition-free and earn associate degrees or enough class credits to transfer to a four-year college or university, where they will be guaranteed admission.

“It’s definitely had an impact and encouraged people to go back to school or to take classes and switch careers,” said Jennifer Worley, president of the City College of San Francisco Federation of Teachers. “So, for sure it has increased enrollment, but we’re still not where we were before the accreditation crisis.”

The free-tuition program is set to expire later this year, but voters will decide this fall whether to extend it for 10 years.

CCSF is not the only struggling community college to experience increased enrollments after starting free-tuition programs.

Morley Winograd, president of the Campaign for Free College Tuition, points to enrollment increases in Tennessee after the state expanded its tuition-free program to include adults last year. Tennessee officials had anticipated 8,000 adult learners would apply for the program. But they received more than 30,000 applications, and nearly 15,000 adult students enrolled.

Winograd said Tennessee's experience is an example of how these initiatives can help community colleges rebound.

The numbers "suggest expanding the idea to adult learners would actually end any enrollment decline," he said in an email. Free City doesn't have any age restrictions and its message is clear -- it's for San Francisco residents.

Mary Rauner, a senior research associate at WestEd, a nonprofit organization that is part of the California College Promise Project, which tracks and provides support for free-tuition programs in the state, said programs that have clear messages about the financial and academic benefits of participating can influence students' decisions about where to go to college, which can lead to enrollment increases.

Davilla said CCSF administrators are also expecting more students to enroll as a result of the college's efforts to increase dual enrollment with San Francisco-area high schools, and also because the college added more online classes to its course offerings.

"We see a lot of room for growth," she said.

Davilla is also optimistic that CCSF's enrollment will return to what it was prior to the accreditation crisis.

"We still have enough of a program base that attracts students and enough underserved students to climb back," she said.

Chan, the CCSF spokeswoman, said some faculty members may see their workload increase or decrease with the programmatic changes. The college is also hoping to shift faculty members into high-demand courses, such as math and English, for which four-year universities grant transfer credit, she said.

Worley said the faculty union disagrees with Rocha’s decision to cut classes.

“We want to see the college rebuild enrollment, and if we’re cutting courses, then we’re shrinking the college,” she said.

Some faculty members fear the changes City College administrators want to implement may alter the mission of the college.

Worley said there has been "a pretty concerted effort" to turn the institution into a junior college focused on increasing access to 18-year-olds so they can transfer to universities. She noted that CCSF already serves young students and the faculty union would be against any changes that limit options for nontraditional students and students in non-credit-bearing courses.

“We want to keep robust and diverse course offerings at City College for the entire community.”