You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/artisticco

Working for a college or university can often be considered a plum job for a student -- with generally flexible hours, minimal to no commute and a relatively easy first professional opportunity.

But according to a new analysis by NASPA: Student Affairs Professionals in Higher Education, institutions of all sorts -- two-year and four-year, public and private -- want and need more money to invest in student employment and to add more positions on campus. These jobs also compete with those outside the university that might pay better, the report shows.

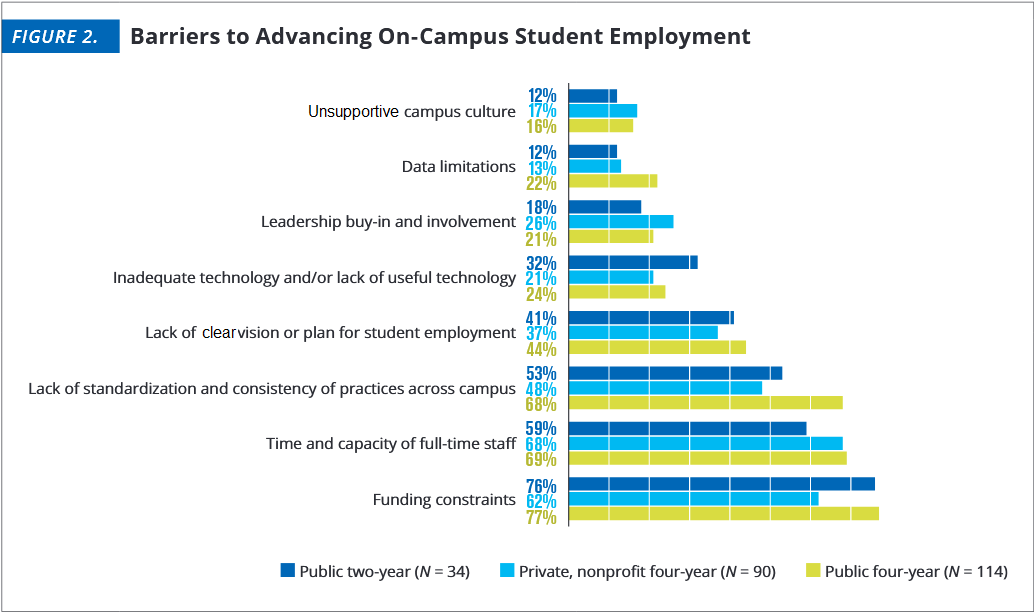

NASPA researchers surveyed student affairs professionals and other employees at 244 institutions, most of them four-year public (47 percent) and private nonprofit institutions (37 percent).

The survey asked respondents to identify barriers in “advancing” student employment on campus. Inadequate funding was generally the top answer, with 77 percent of respondents at public colleges and 62 percent at privates reporting that funding was a problem. About 76 percent at two-year institutions in the survey also reported that limited funding was an issue.

About 64 percent of respondents said that in the next three to five years they’d like to increase the hourly wage of student workers. And 59 percent said they wanted to add to the number of student positions.

About 64 percent of respondents said that in the next three to five years they’d like to increase the hourly wage of student workers. And 59 percent said they wanted to add to the number of student positions.

The survey found that the top two “environmental factors” affecting student jobs were minimum-wage changes and a competitive off-campus job market. The report didn’t provide a range of how much students typically are paid for on-campus positions. But it said many students from all types of institutions work between 11 and 15 hours a week, which can be fewer hours than is required by retail jobs off-campus, said Amelia Parnell, NASPA’s vice president for research and policy and one of the report’s coauthors.

On-campus jobs benefit students in ways their off-campus counterparts don’t, Parnell said. For example, she said, staff members recognize that a worker “is a student first,” and they can be more flexible about scheduling.

Omari Burnside, assistant vice president for strategy and marketing at NASPA and a co-author of the report, said that in some cases low-income students might need to seek off-campus jobs that pay more than those offered by a college. Institutions said they sometimes help students find jobs with better pay. And Parnell said some on-campus positions last longer than single semester or academic year, which means that students, just like if they were working off-campus, are able to earn promotions and raises.

She said students shouldn’t ignore off-campus opportunities. But campus jobs can be uniquely beneficial, said Parnell, often by not requiring a car to go to work or by helping student employees develop a mentor-mentee relationship with a boss.

“I think we do it owe it to them to make it as fruitful as possible,” Parnell said of on-campus jobs. “With other jobs, it’s much more transactional -- you do the job, you get paid. College is much more than that -- with this particular work environment, it should be a living and learning community.”

The survey's other findings include:

- 81 percent of institutions surveyed said the goal of off-campus employment was to prepare students for a career, 78 percent said it was to improve students’ financial security and 69 percent said the jobs were meant to retain students and help them complete college (respondents could check more than one answer).

- All of the four-year and two-year public colleges surveyed received some form of federal work-study funding, as did 99 percent of four-year private institutions.

- Only 1 percent of students at four-year public institutions worked more than 21 or more hours a week; 4 percent of students at two-year colleges worked 21 or more hours a week.

- The campus student affairs office employed the most students, followed by an institution’s recreation or fitness center.

- About 82 percent of all institutions surveyed maintained some sort of centralized job board; 55 percent directly reached out, either by email or face-to-face, when students matched the characteristics of a job; and about 49 percent of institutions used new student orientation to showcase their jobs.