You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

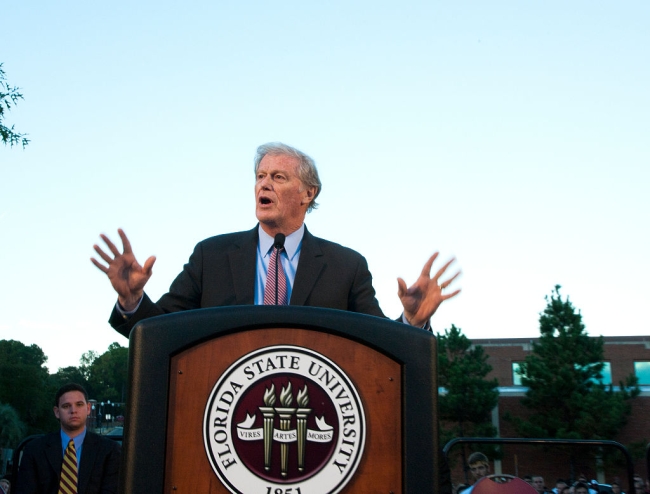

Florida State University president John Thrasher

Mark Wallheiser/Stringer via Getty Images

Dozens of college presidents have announced that they will retire or otherwise step down before or at the end of June 2021, the close of the current fiscal and academic year.

The pandemic provides an unusual backdrop for leadership transitions, although many retiring presidents have said the pandemic was not the primary reason for their departure.

The apparent flood of retirement announcements makes perfect sense, said Rod McDavis, managing principal at AGB Search, a higher education leadership search firm. Many presidents who would have announced their departures in the spring held off. Instead, they’re sharing their plans this September, alongside other planned fall announcements.

“Because of the pandemic, I think most presidents who were planning to step down simply didn’t want to make an announcement, because you don’t want to make that type of announcement with a crisis occurring,” McDavis said.

That was the case for Mary Marcy, president of Dominican University. She had planned to announce her departure in March. And then the pandemic arrived on campus.

“So, we waited a little bit, just to see if it was still a reasonable decision both for the institution and for us personally,” she said.

Six months later, Marcy announced on Sept. 3 that she plans to retire soon. She’ll be leaving the California college in June, at the end of the 2021 fiscal year. Dominican University will turn 130 this year, marking the close of its current strategic plan, and after about a decade at the helm, Marcy believes it’s a good time to pass her baton to a successor.

“Ten years is a really good time frame for a president,” Marcy said. “It’s long enough to hopefully accomplish what you were asked to do and maybe a little bit more, and then at that point it’s a good point to reassess and either have the next big vision for the institution, or let someone else step in.”

The departure wave has also hit higher education associations. Mary Beth Labate announced Sept. 10 that she would end her tenure as president of the Commission on Independent Colleges and Universities in New York. She’ll step down in December of this year.

“If anything, the pandemic gave me some pause on my decision,” she said. But it did not motivate her to leave the post.

Late spring and early fall are popular times for retirement announcements, said McDavis, of AGB Search. Either season typically gives governing boards time to identify and hire a new president.

Fall announcements in particular fit well into the rhythm of the academic year, said Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education and a former U.S. under secretary of education in the Obama administration. He could not say for sure whether the recent number of announcements is unusually high this year.

"Trustees will have the opportunity to list a position and find candidates and be able to recruit them in the spring, so that they could then take the reins during the summer," Mitchell said.

AGB Search has noticed an increase in requests from colleges looking to fill soon-to-be vacant presidencies, McDavis said. Many institutions are reluctant to introduce an interim president during the pandemic, he said.

Some presidents delayed not only their announcements but also their actual retirements. The future of some college presidencies was a talking point last spring. Several leaders decided to delay their departures as the pandemic affected their campuses, including Tim White, chancellor of the California State University system.

John Thrasher, president of Florida State University, had planned to leave in November after six years at the university. At a recent board meeting, he agreed to stay at the helm until the university finds a new president.

“I really think I’ll be here probably until after the first of the year, maybe even longer, depending on the scope of the search and how deep the applicant pool is,” Thrasher said. “I’m just going to finish strong and get out. We’ve got a lot to do between now and then.”

Mitchell said that none of the presidents he’s spoken to have cited the pandemic as their reason for leaving. But for some, the pandemic provided new clarity on what is important for their families, careers and futures.

“For presidents who are at some distance from a significant portion of their families, this takes a toll,” said Mitchell, who is a former president of Occidental College. “It affects our sense of health security. It certainly affects our families for presidents who have aging relatives. It has to be a consideration.”

Family and health were deciding factors for Roger Casey, president of McDaniel College in Westminster, Md., who announced his retirement last week. He is at high risk for complications of COVID-19.

“I’m an only child and I’ve got a couple of octogenarian parents that live in South Carolina,” Casey said. “I’ve never thought of that as very far away. You just hop on a plane and you’re there in an hour. You don’t hop on a plane and get there in an hour anymore.”

The increasing age of college presidents could also be behind the many retirement announcements. A 2017 ACE study found that the average age of college presidents is ticking upward, from 60.7 in 2011 to 61.7 in 2017. More than 10 percent of presidents were 71 or older in 2017, and presidents are spending less time in their jobs than they used to. The average presidential tenure was 6.5 years in 2017, down from seven years in 2011.

More than half of the surveyed presidents told ACE in 2017 that they planned to leave their jobs in five years or sooner. Three years have passed since the study was published, and the wave of recent resignation announcements could be related to this predicted exodus of college presidents.

Andrew Westmoreland, president of Samford University in Birmingham, Ala., had been considering his retirement long before the pandemic. He is 63.

“I’m coming up on 23 years of being a college president, so it probably was about 22 years ago that I decided I would like to quit,” he joked. He knew for a while that he would likely retire in 2021 or 2022.

The transition out of office will likely be different than it would be in a typical year, Westmoreland said. But he doesn’t know exactly what shape it will take yet.

“I had assumed that the transition would be similar to other transitions, but I would imagine in reality there would be much more in the way of Zoom calls and Microsoft Teams calls with introducing the new president to groups,” he said.

Additional presidents leaving office or retiring for different reasons include Lori Varlotta of Hiram College, who is taking up the presidency at California Lutheran University, John Simon of Lehigh University, the Reverend Scott Pilarz of the University of Scranton, John Broderick of Old Dominion University, Mary Cullinan of Eastern Washington University, Tom Manley of Antioch College, Michael McRobbie of Indiana University the Reverend Philip Boroughs of the College of the Holy Cross, as well as Mark Ojakian of the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities system. Also recently announcing departure plans are University of Chicago president Robert J. Zimmer and Valencia College president Sandy Shugart.

Running a college is never easy, but the pandemic has exacerbated already-existing financial woes for many colleges and added a slew of public health concerns that have kept colleges under the national microscope. On top of that, a shift in national demographics is expected to move student bodies away from the wealthy 18- to 24-year-old white students many institutions traditionally served, increasing colleges’ need for robust financial aid and flexible programs.

“College presidencies are very hard jobs, and there’s not a lot of evidence that they’re going to get easier any time soon,” Mitchell said.

None of the executives Inside Higher Ed interviewed cited the pandemic as the biggest challenge of their tenure. Labate recalled a difficult battle with the New York State Legislature over the state’s free college tuition program, called the Excelsior Scholarship, and reshaping how the Legislature understood financial aid. Thrasher pointed to budget concerns and public funding battles. For Westmoreland, it was the “collective burden of the job” and being able to reach consensus with many different constituencies.

Asked what they’ll do after their departure, almost every president had the same answer: sleep.