You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

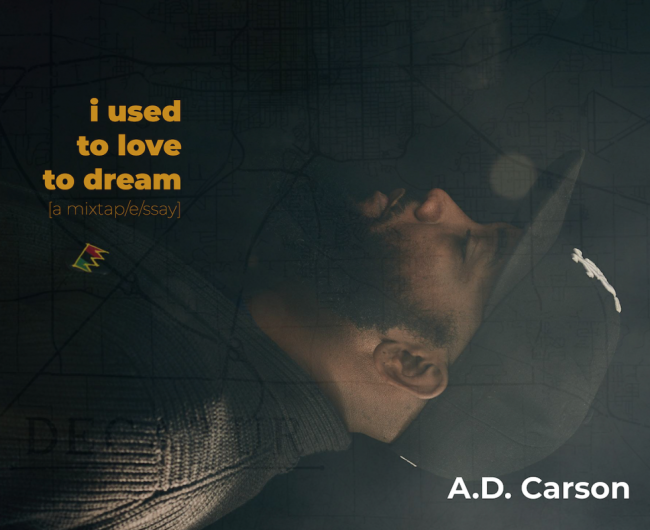

i used to love to dream/A. D. Carson

University of Michigan Press

Hip-hop studies has been around for almost as long as hip-hop itself. Many experts trace rap back to the 1970s Bronx, and Tricia Rose published her groundbreaking Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America in 1994. Other books and publications followed.

Marcyliena Morgan founded the Hiphop Archive and Research Institute at Harvard University in 2002, after previously working on it at the University of California, Los Angeles. Cornel West has published several spoken-word and hip-hop records.

Many institutions have long offered courses in hip-hop, and some list full programs of study.

Yet until the University of Michigan Press published A. D. Carson’s new i used to love to dream, no academic press had published a peer-reviewed hip-hop album.

Carson, assistant professor of hip-hop and the global South at the University of Virginia, approached several academic presses with his project -- the third in a series called Sleepwalking that began with his 34-track dissertation album, at Clemson University. He partnered with Michigan based on its editors’ collaborative approach, including questions about how to tackle the peer-review process, he said recently.

“They understood what they didn’t understand and some of the limitations on what they believed they could do, and being honest with people about those kinds of things is a way to build trust,” Carson said. “It’s important to be in community and in collaboration with the people who you’re working with. You want that, to have faith that the project you make is going to be a thing you’ll be proud of. You don’t want to walk away from this feeling like you don’t want to listen to the album because it doesn’t sound like me.”

The published album does sound like Carson, in a deeply personal way. An open-access, eight-track exploration of the idea of home, i used to love to dream is probably more personal than most scholars -- especially untenured ones -- would want or dare to make their work. That makes it richly relatable to anyone who’s ever felt between worlds. Carson raps about not feeling fully at home as an academic living in Charlottesville, Va., or back in Decatur, Ill., where he grew up and which he sought to leave behind, but still misses.

“Is it really a win when your team ain’t there?” he asks in the song “Asterisk.”

where you wanna be

& what you understand will be the cost is

something to consider when you off

inventing the life you wanna live,

then the life you gonna live,

& the life you used to live

will be incongruent. it’s

different when you do it than

when you thought you knew it.

More between-ness: Carson is an alcoholic who’s been sober for 10 years, as he says in a song called “Ampersand,” but “some days i really hate i chose therapy over Jameson.” He’s a Ph.D. working at Thomas Jefferson’s university but as a Black man knows that doesn’t insulate him from systemic racism and even violence -- including at the hands of police. As he says in “Just in Case”:

what i’m asking

is for you to ask,

& keep asking,

if those sworn to protect & serve say to you

that, in order to properly execute their duties, it was

necessary to execute me,

& the truth as you know it doesn’t match up with the truth

you know to be,

it’s likely because the truth that’s in between the two is too

inconvenient for those who have the power to speak it.

No topic is taboo for Carson. While he’s aware of his relative privilege as a tenure-track professor, he said he’s unwilling to sacrifice what makes him who he is to belong in academe. Like others who have survived adversity, one of Carson’s coping mechanisms appears to be radical honesty, including with himself.

“There is not a box that i will fit within,” he declares in the song “Stage Fright.” Carson lives “within the complicated, complex storm after the calm. It’s further explanation of my thicker skin.”

Sara Jo Cohen, senior acquisitions editor at the University of Michigan Press, said she chose to work there because of how the press is “pushing the boundaries of scholarly publishing,” largely through its community-based, open-source Fulcrum platform.

In Carson’s project in particular, she said, “I saw an opportunity to challenge what counts as scholarly publishing in terms of both form and content.” i used to love to dream was an “opportunity to support cutting-edge scholarship that we were uniquely able to take on because of the digital affordances of Fulcrum.” Not only was the press able to publish tracks, she said, it could publish a short documentary and lyrics and notes in a book-like format accessible to scholars and tenure and promotion committees.

In a video addressing the peer-review process for the album, Cohen said she started to think about this novel process by asking Carson and her series editor, Loren Kajikawa, associate professor of musicology at George Washington University, what kinds of questions they wanted to see answered by reviewers. Cohen shared with Carson and Kajikawa typical review questions for a written work and then asked them what might be adjusted to better assess a sonic project. This made Carson confident that instead of being pro forma, the process would be one that actually improved the album prior to publication.

Ultimately, Kajikawa said in the video, “I think both peer reviewers did a good job of noting that although hip-hop studies has in the past couple decades really grown into a vibrant, interdisciplinary field, A. D.’s work is finally giving us hip-hop as scholarship.” He added, “I think I trusted them to believe that A. D.’s work doesn’t require translation or alteration to be appropriate for an academic context.”

In response to the tailored questions about i used to love to dream, Cohen said, both peer reviewers “really focused their comments on the scholarly interventions that the project is making, the importance of this intervention and how to best present this project so that it could reach the widest possible audience.”

The project's final open-access, text-rich format means more exposure for Carson’s work -- nearly 4,000 views so far. Will scholarly presses publish more rap albums?

Cohen said the industry is “starting to see more work that, like A. D.’s, challenges what scholarship looks and sounds like.” Wilfrid Laurier University Press, for example, is publishing a scholarly podcast called Secret Feminist Agenda, which, in Cohen’s words, “is very cool.”

“I’ve heard rumors that other peer presses are considering publishing peer-reviewed albums, though I haven’t heard about other peer-reviewed rap albums yet,” Cohen said. Beyond rumor, Cohen is seeing what she described as a “strong commitment in the university press community to publishing antiracist work, so I anticipate that we’ll see a lot of exciting work by Black scholars on Black lives in the coming years. And I hope that scholarship will take nontraditional as well as traditional forms.”

Carson counts Ralph Ellison, whose Invisible Man partially inspired the Sleepwalking series, among his academic and artistic influences. Others are Rose, Fred Moten, Imani Perry, James Baldwin, Claudia Rankine, Gwendolyn Brooks, Jean Toomer, Walter Mosley, Chenjerai Kumanyika and Sylvia Wynter.

Musically, his influences include Preme, Eightball & MJG, Lauryn Hill, J-Dilla, Little Brother, Outkast, gospel that his mother and grandmother listened to, and “all kinds of oldies that my parents loved.”

Stylistically, Carson said he tries to employ modes of hip-hop that will “most effectively communicate the piece I’m writing.” He worked with other musicians on i used to love to dream to create music that sounds like “home,” he added.

“I wouldn’t call it underground or lo-fi, though I certainly understand why someone might. I’d similarly understand if someone called some of it experimental, though I’d say that’s something lots of hip-hop I’ve loved does consistently in so many different ways.”

Kumanyika, one of Carson’s influences and a professor of journalism and media studies at Rutgers University, wrote in a review of the album that it “cannot be reduced to the sounds, images, texts and thin genre descriptions that comprise it. With this disturbingly personal offering, Carson gives us a dope critical process of inhaling and engaging today’s most pressing questions about home and national identity, empire and the geography of oppression, and the intimate politics of survival and transformation.”

He added, “I’m not sure if disciplines -- as currently embodied -- deserve or can handle this hit, but all of us need what is revealed on this journey.”

Carson doesn’t really like questions about the growing “legitimacy” of hip-hop in academe -- almost as much as he doesn’t like it when people hear what he does and immediately ask if he’s seen Hamilton (it happens a lot).

Yet even Vice President Mike Pence has seen Hamilton, and rapper Kendrick Lamar was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2017, for DAMN. What about that?

Carson explained hip-hop moving ever more into the mainstream like this: “It feels more than Kendrick getting a Pulitzer, the Pulitzer got a Kendrick. It kind of does more for the Pulitzer than it does for Kendrick Lamar.” Put another way, he said, hip-hop is “ubiquitous,” so “what took so long?”

Similarly, as for a major academic press publishing his hip-hop album, Carson said that “hip-hop and related art were being taught in the ’80s … I’m happy this album is what it is, but it also means we should be asking what took so long.”