You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

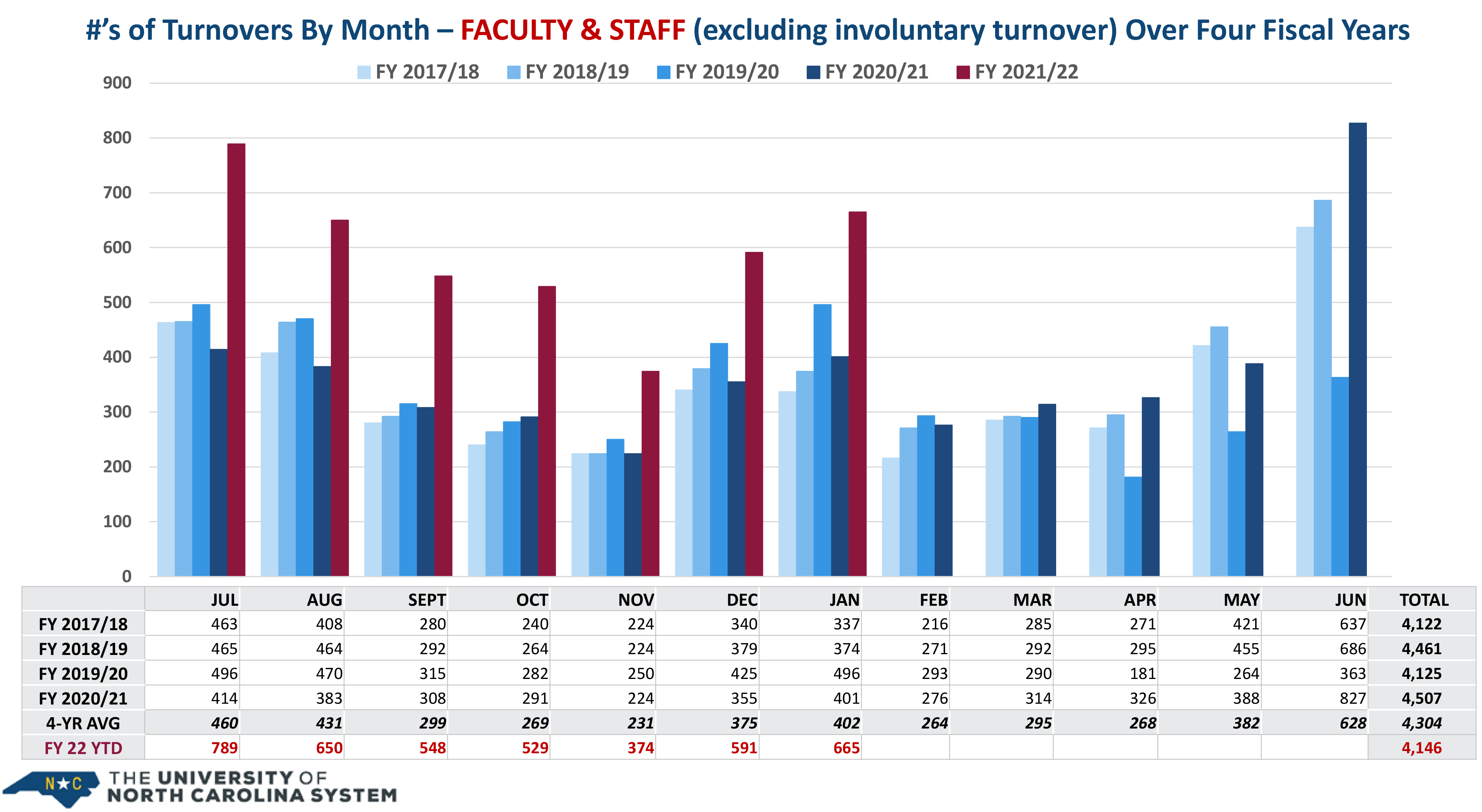

After months of unspectacular numbers in the first year of the pandemic, turnover by faculty and staff in the University of North Carolina system suddenly doubled in June 2021.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

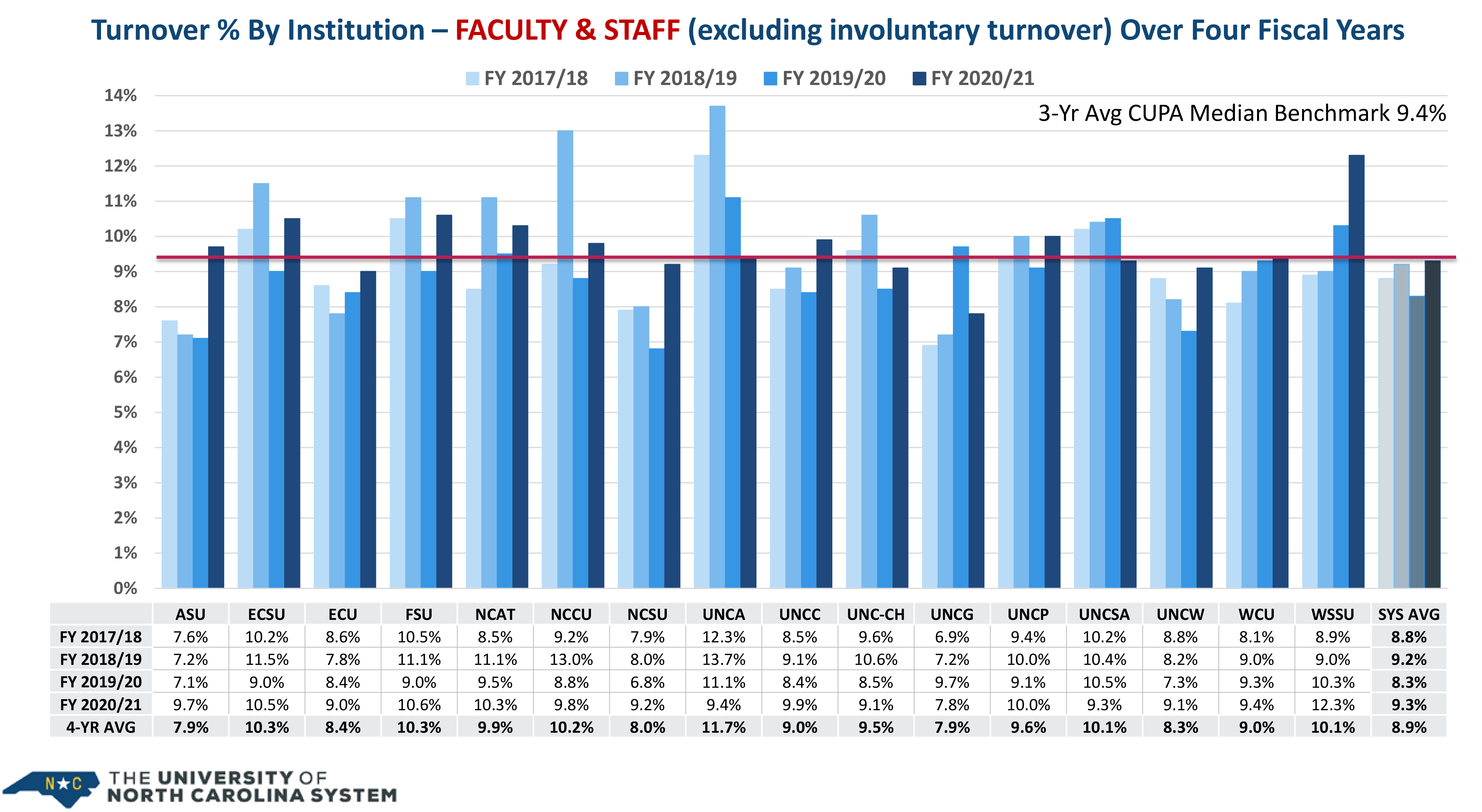

When the Board of Governors of the University of North Carolina system recently received data showing a sudden and dramatic increase in faculty and staff turnover last summer, it raised questions about whether faculty and staff were leaving or changing jobs at the system’s 17 institutions at the same rate as other systems across the country—and as often as employees in other sectors.

The data presented by the Committee on University Personnel at an April 7 board meeting showed 827 “employee-driven separations due to employee resignations, including transfers to other institutions (but not including movement within the same institution)” in June 2021. The total number of resignations and transfers was more than double the number of employee departures in each of the preceding 10 months, including 338 that took place in May 2021 and 363 in June 2020.

The turnover in faculty alone in June 2021 was even more pronounced—293 compared to 147 in June 2020—and the most since June 2019.

Matthew Brody, UNC system senior vice president and chief human resources officer, presented a summary report of the data during the board meeting held at Western Carolina University. He noted that the turnover appeared to be “a direct outcome of the COVID-19 event.”

That point was reinforced in the written report, which stated, “Turnover dropped significantly month-to-month for the first 5 months of the pandemic (April-August 2020) then stayed at levels consistent with previous years until June 2021. Starting in the summer of 2021, the University’s turnover rates increased substantially across the board and this trend continues to-date.”

Kevin McClure, an associate professor of higher education at UNC Wilmington, was not convinced the pandemic played such a singular role. He believes the national factors that accelerated what has become known as the Great Resignation had the same effect on UNC campuses and are still playing out in academia.

McClure, who is also director of communications at the Alliance for Research of Regional Colleges, highlighted the turnover numbers in the state system on his Twitter account.

“I think many of the reasons for departure are connected to issues that pre-date the pandemic,” he said in a Twitter thread about the turnover in the UNC system.

McClure outlined those factors earlier this month in a discussion on Inside Higher Ed’s podcast The Key. He said they include “burnout, demoralization, disengagement,” issues that “have been around a long time and are not going away when the pandemic does. The pandemic revived them.”

The U.S. was also more than a year into the pandemic and the national racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd by the time of the employee turnover spike. Many people believe both events played a role in employees’ decisions to resign or leave for jobs elsewhere. While those events were also factors at UNC Chapel Hill, many point to the controversy over the failed hiring of journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones as particularly damaging to perceptions about the workplace climate on campus. Faculty and staff turnover at Chapel Hill increased from 8.5 percent to 9.1 percent from fiscal year 2020 to 2021. It was one of several UNC campuses to experience a rise in resignations and departures.

Board member Kellie Hunt Blue, chair of the Committee on University Personnel, explained in her report to the board at the April 7 meeting that people left their jobs for many reasons.

“System office staff attributes a great deal of this to the Covid-19 event and the so-called Great Resignation, which is a nationwide challenge for many private and public sector employers,” she said. “While it is not clear how long these trends will continue, it is a matter of great concern to our UNC System human resource professionals, and will be monitoring it very closely.”

Blue also told the board that “this trend continues to date,” and she added that Brody, the chief human resource officer, “indicated that he will provide frequent updates on this topic to the committee.”

There was no public discussion by the board members of the information presented, and no action was requested or taken. The board and members did not respond to requests for comment.

Brody said he was not surprised when he and his staff saw the numbers on faculty and staff turnover. “I didn’t necessarily know it would be that high, though,” he said.

He said what they saw and heard “anecdotally” in the UNC system was not unique to them, or to higher education, and reflected what was going on across the country. The sharp rise in employee turnover last summer prompted a month-by-month breakdown of the turnover over the previous four years, something not ordinarily done for their annual Board of Governors report. Being transparent with the numbers to the public and the board was a priority, he said.

The board members understood the gravity of the numbers, Brody said, as many of the board members were seeing the same trends in their own workplaces and were concerned about what was happening in the UNC system.

Brody said his department is monitoring the situation closely.

“I don’t think we’re taking this casually at all,” he said. “I think there’s a variety of things we’ll be focusing on in the months ahead, including continuing monitoring this month by month.” That will include examining compensation, benefits, perks, recruitment and retention in faculty and staff positions at every campus, he said.

The biggest challenge will be interpreting the data as both the pandemic and the Great Resignation continue.

“I don’t know if this is something that is going to be a sustained trend. This has been an unusual 18 to 24 months,” he said. “I cannot conclude that the last six months of data will be the next six months of data. We just do not know … We have to be proactive.”

McClure noted that while the university system’s individual campuses had their own problems that might have accelerated turnover, the hard questions employees were asking and the re-evaluations they were making of the institutions’ mission were at the heart of the dissatisfaction driving people to quit.

“That’s definitely a big part of it,” he said. “Higher education is implicated in a lot of these broader conversations about workplace conditions and workplace cultures. Faculty and staff have come to terms with mortality in an entirely different way, and thus re-evaluates the place of work in their lives.”

Many observers saw the highly publicized and widely criticized failure of Chapel Hill’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media to hire Pulitzer Prize–winning author and journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, a Chapel Hill alumna, as a glaring example of the problematic workplace culture on campus. The controversy also revealed long-simmering resentments about racial inequity there and at other UNC campuses.

There were also questions and angry discussions about the lack of concern for the health and safety of UNC faculty members and staff as COVID-19–related deaths of faculty members and staff at colleges across the country rose during the height of the public health crisis. UNC faculty members pushed back against requirements that they teach in person and engaged in a public campaign that criticized the system for not prioritizing their health.

Deb Aikat, an associate journalism professor at Chapel Hill, agreed that the pandemic brought the problems faculty and staff were having in the UNC system to the surface. “In many ways, this is a problem that has gone on for many years, and I’m glad that we’re finally discussing it in ways that are credible. When we’ve brought it up before, nobody listened to us.”

Aikat believes faculty and staff members stayed put in the first year of the pandemic to get through it without additional disruption to their lives, but “the moment the pandemic eased up, people started looking for other jobs. If they could withstand the stress of moving and changing jobs, they were going to do it.”

In many cases, he said, other universities and the private sector offered better salaries and working conditions, and employees either used that as leverage at their current jobs to get raises, or they simply left.

“The university system is not rewarding our hard work and dedication. They’re looking at it with a ‘take it or leave it’ attitude,” Aikat said.

“What happened in Chapel Hill wasn’t necessarily reflected on every campus,” he said. The faculty that left expressly because of the Hannah-Jones issue “would be a marginal number, and it was mostly people of color. But these sort of things would force you to rethink where you were. There are certain instances and situations that contributed to it.”

Andy Brantley, president and CEO of the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources (CUPA-HR), said the turnover within UNC system is not unique and reflects national trends in higher ed.

“It is everywhere. It is at urban institutions, it’s at rural institutions, it’s at public institutions, it’s at private institutions,” Brantley said.

He said he has not seen other state or public systems make data on faculty and staff turnover available the way UNC did, but surveys and conversations with the organization’s 33,000 members at some 2,000 institutions bear out that turnover is widespread in academe. He agreed that the pandemic was not the sole cause and was more of a catalyst.

According to a survey CUPA-HR released in November 2021, “workers are experiencing a misalignment between their actual work arrangements and their preferred work arrangements and … this misalignment is related to the likelihood that they will seek other employment.” That misalignment was expressed largely by a desire for more remote work options and correlated with an increased interest in looking for another job within the next year, the survey said.

Brantley said universities bear the burden of reversing the trend.

“Higher education has to rethink the ‘so-what’ factor—what factors make employees come to our institutions and stay there—and eliminate the things that are an impediment to coming here,” he said. “What is the experience for so many of them—extraordinary hours and extraordinarily low pay. We have to think of the worth-it factor. Why is our institution ‘the’ place to work? Why come here instead of the private sector, or even other institutions?”

The answer to those questions, Brantley said, “might be a lot different than it was in 2018. We have to be willing to pull forward all the things that we have learned in the last two years.”