You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Members of American University’s staff union kicked off a planned weeklong strike Monday by picketing at the law school.

Liam Knox

Monday was the start of Welcome Week at American University. Students and parents arriving at the Washington, D.C., campus were greeted not only by smiling university ambassadors but also a picket line of more than 100 members of the university’s staff union, gathered for the first day of a weeklong strike.

The strike, announced Aug. 11, was approved by 91 percent of the union, which represents over 500 professional staff members in a wide range of positions. They are mostly student-facing roles, including academic advisers, program coordinators, library staff and support staff in the admissions and financial aid offices.

They are demanding higher wages in contract negotiations, which started in May 2021 and came to a standstill this summer after the administration made concessions on benefits and working conditions but failed to meet them on pay. None of the strikers will receive pay for as long as the labor action continues.

“I really hope this is the final pressure point required to bring administration to the table and finally settle this,” said Sam Sadow, a visual arts librarian who’s been involved in contract negotiations since they began last year.

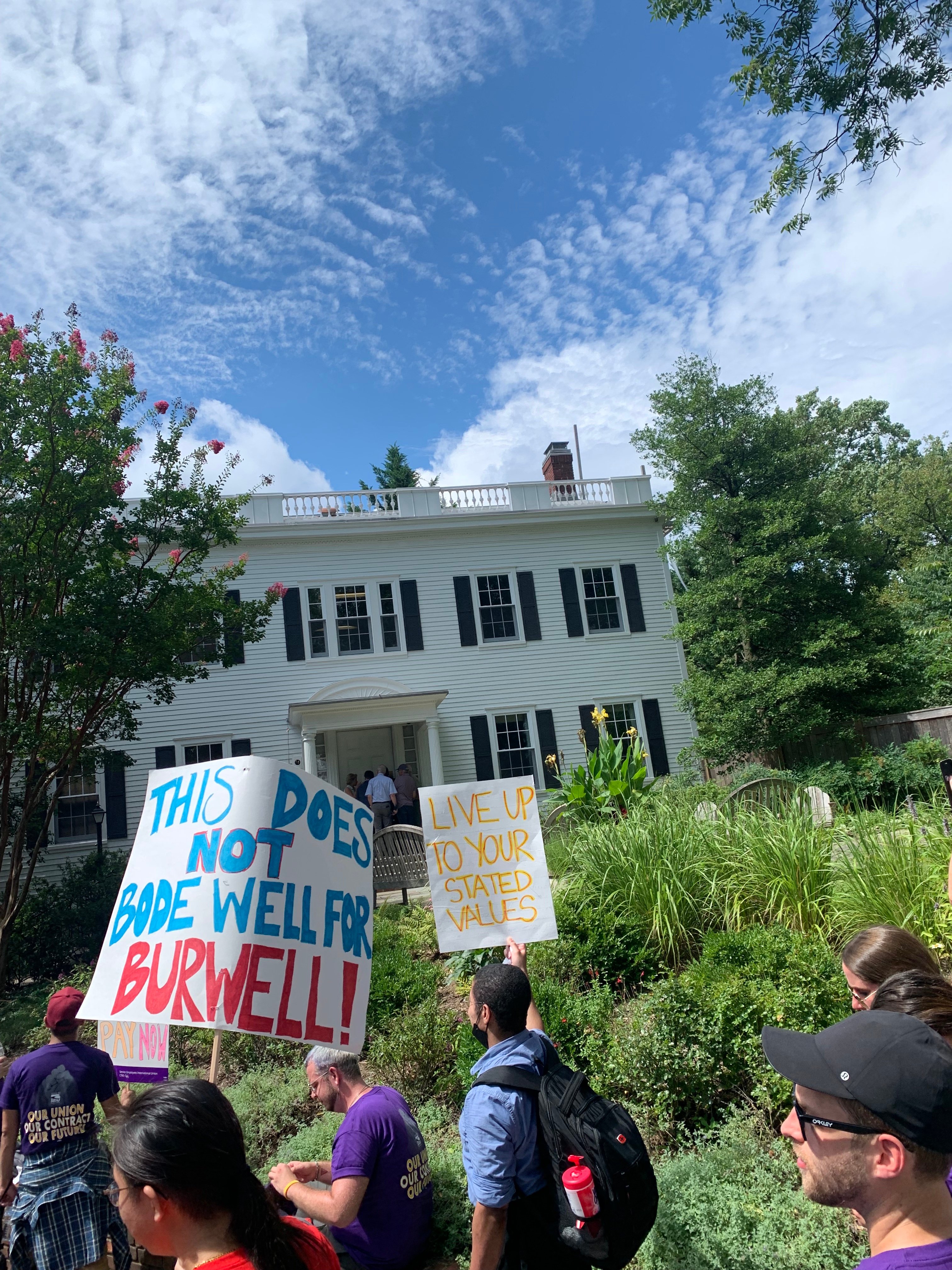

Hoisting handmade signs and equipped with fans and water bottles to combat the heat, the strikers started by picketing at AU’s Washington College of Law, where first-year law students were starting orientation and returning ones had their first day of classes. Later they marched to the main campus to protest outside the residence of university president Sylvia Burwell.

In a statement released to AU community members Sunday, Burwell said the administration’s latest position on staff contracts represented its “best and final offer.” That offer includes a 2.5 percent salary increase for all union members and a 1.5 percent increase to the university’s “performance pay pool” for merit-based raises determined by performance reviews. It also includes raising base salaries across the board to "reduce salary compression for long-serving employees."

In a statement released to AU community members Sunday, Burwell said the administration’s latest position on staff contracts represented its “best and final offer.” That offer includes a 2.5 percent salary increase for all union members and a 1.5 percent increase to the university’s “performance pay pool” for merit-based raises determined by performance reviews. It also includes raising base salaries across the board to "reduce salary compression for long-serving employees."

Burwell added that recent financial setbacks—including nearly $100 million in losses during the first year of the pandemic—factored into the university’s offer.

“I want to assure you that the university has negotiated in good faith,” she wrote. “In this process, we have to consider the health of the institution. With our deep dependence on tuition, we must be thoughtful stewards of our resources.”

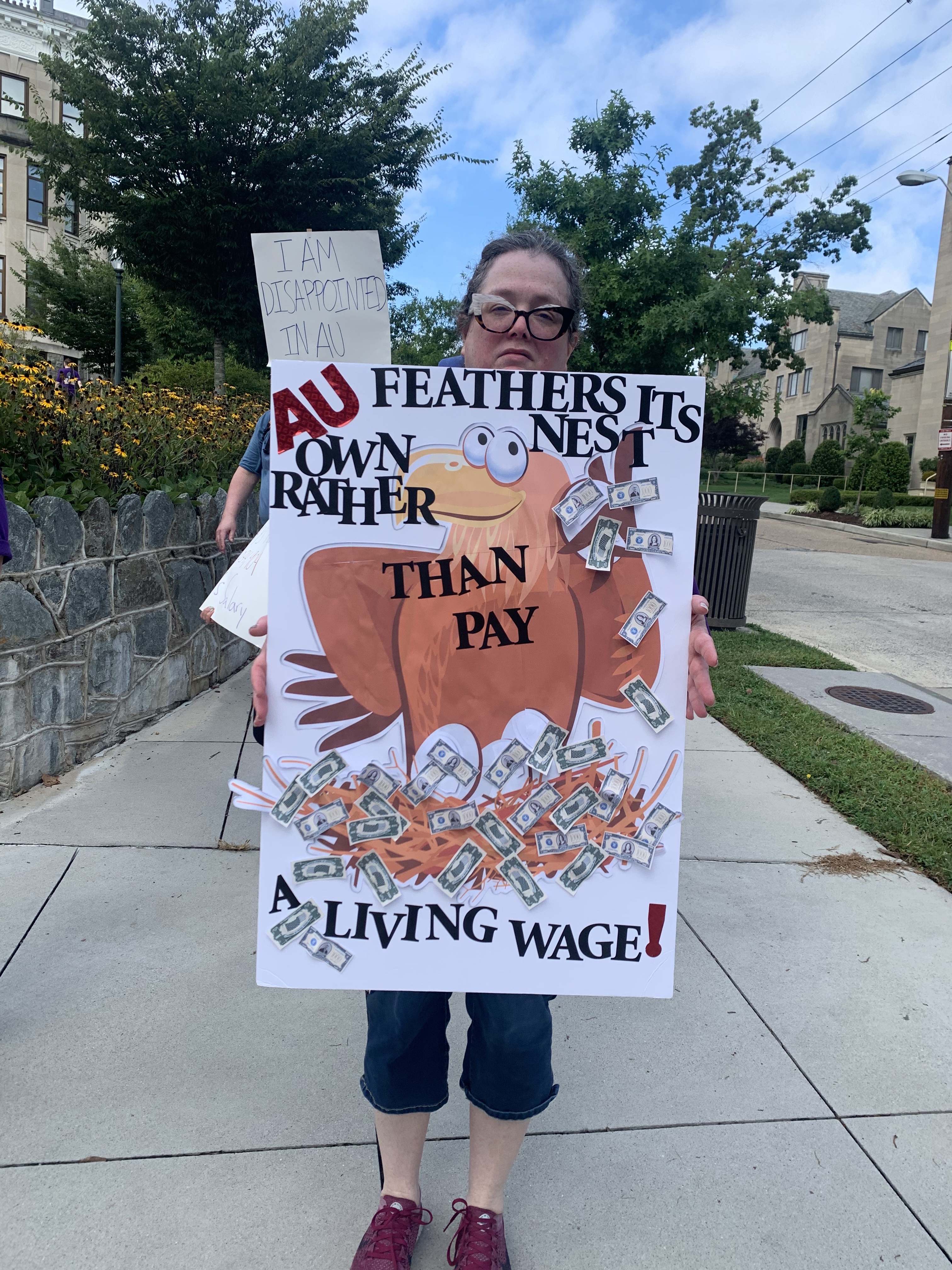

But the union says American’s offer doesn’t allow staff members to live comfortably in a city as expensive as Washington, D.C.—a problem that members say has hurt retention. The union’s contract demands include a 5 percent wage increase for all union-represented staff for the first year of the contract and an additional 4 percent the next.

“If they say the market has shifted 5 percent and they need to pay new hires 5 percent more in a given year, then people who have been here longer should see those gains as well,” Sadow said.

Kelly Jo Bahry, an assistant director in the study abroad office, has worked for the university for over 15 years. She said she was surprised the administration wouldn’t meet the union’s demands and that she never expected to go on strike—the first time ever in her long career at the university.

“We’re not asking for the heavens and the stars,” she said. “We’re asking for basic wages.”

Empty Cubicles, Stagnant Wages

The union, organized by SEIU Local 500, won its election in 2020 at the height of the pandemic, riding a wave of collective organizing in higher education. Sadow said the primary motivating factors for AU staff were low and flat wages, which drove high turnover rates in many student-serving offices.

“You look around AU and see empty cubicles all over, empty offices … Staff were leaving in droves, and the No. 1 reason was stagnant wages,” he said. “That really begins to affect services for students and faculty.”

Amanda Kleinman is an academic coach, helping struggling students keep their grades up. She said turnover in her office, which assists about 1,100 students each semester, has been rampant. A few months ago, two of her colleagues left for higher-paying jobs, making her the only academic coach left for AU’s entire undergraduate body.

“I am committed to student support and will do my best, but I’m only one person,” she said. “I can realistically only see about 40 students a week.”

A university spokesperson said all the affected departments have prepared continuity plans for the strike. But the first week of classes is a particularly disruptive time to withhold services from students who might need help with class scheduling or course-load advising, or who want to attend an introductory program meeting.

from students who might need help with class scheduling or course-load advising, or who want to attend an introductory program meeting.

“All of the staff are very much involved in move-in week … there’s a lot of welcome-type activities we help run,” Kleinman said. “This is a different kind of way to get oriented to the university.”

Strikers said the union knows this and chose Welcome Week specifically because it would maximize visibility and highlight what they say is the undervalued role of professional staff at American.

“I think it looks really bad for the AU administration,” Bahry said. “As a student, I’d be wondering what kind of institution I’m a part of.”

William Herbert, executive director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College, is the co-author of a 2020 study on the prevalence of organized labor stoppages in higher education. He said that while there is a long history of union organizing among professional staff at colleges and universities, militant tactics have become more common in recent years.

“There’s been a marked increase in strikes at higher education institutions, and there’s also a lot more community and student support for those strikes,” he said.

That support has been apparent in donations to the union's strike fund, which had raised over $26,000 as of Monday.

Herbert added that most of the time, unions threaten to strike only to bring managers back to the negotiating table when talks reach a standstill. But he said the fact that this is the union’s first contract with the institution raises the stakes—and the odds of following through on the threat.

“Reaching a first contract in collective bargaining is one of the most challenging moments for both sides,” he said. “They are often very difficult to reach and end up shaping the development of the collective bargaining relationship moving forward.”

Strikers Speak Out

Bahry said she didn’t want to strike, and that taking a week without pay was difficult for her. But it would be even more difficult to keep getting by on her current salary, she said—or to explain to her children why she declined to support the union.

Her family recently had to move from the city to Falls Church, Va., because her pay hasn’t kept up with the rising cost of living in D.C. When they did live in the city, she said, she and her husband shared a one-bedroom apartment with one of their sons for five years.

“My quality of life has decreased the longer I’ve been here because of wage stagnation. When I go into the grocery store, I have to make some hard decisions, and that is very difficult after 20 years of being affiliated with this institution,” she said. “I imagine anyone in AU administration living for one month on the wages they provide staff would be a big learning experience.”

Kleinman, who is almost 50 years old, said that in her four years working for American—and 11 working in higher education—she hasn’t made enough to afford to move out of her group house in Mt. Pleasant, where she’s lived for the past two decades.

“I love working with college students, but I never expected how flat and low the pay would be,” she said.

A university spokesperson said there are no current plans for administrators to re-enter contract negotiations.

Today, union members will gather again, this time outside the Kogod School of Business, for the second day of the strike. (This paragraph has been updated to correct the name of the AU business school.)

“We will not give up,” Sadow told the crowd outside of Burwell’s house. “We will be back tomorrow, the next day, as long as it takes.”