You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A state law limits the number of out-of-state students who can attend the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images

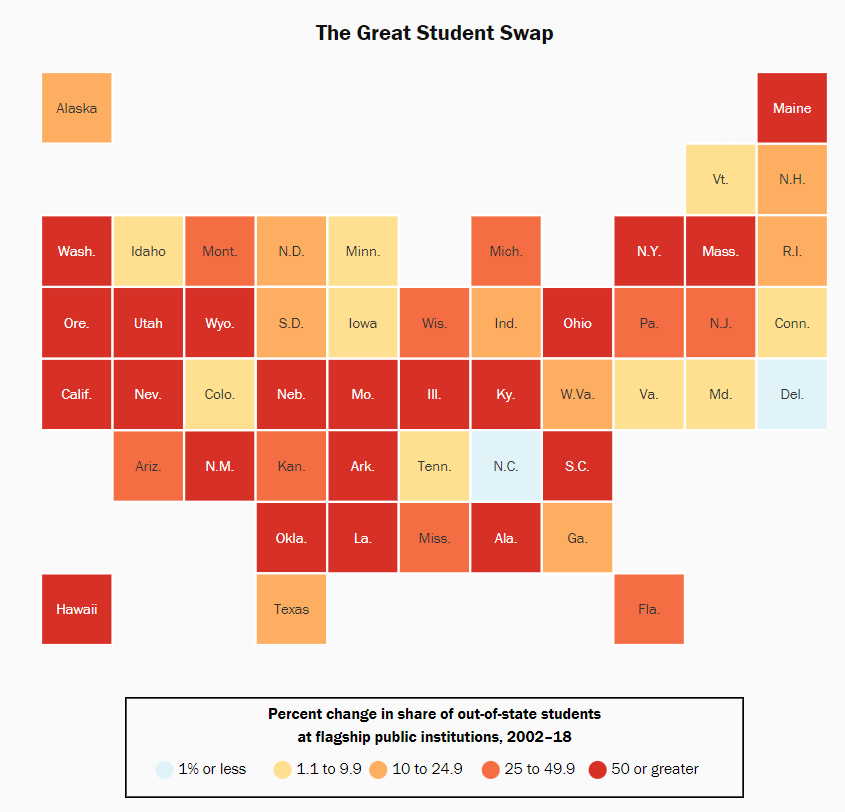

All but two public flagship universities nationally increased the percentage of out-of-state students in their freshman classes from 2002 to 2018, according to a new report from the Brookings Institution. The share of out-of-state students rose 55 percent, on average, after 2002, while the percentage of in-state students dropped 15 percent on average, the report showed.

Aaron Klein, a senior fellow in economics studies at Brookings, analyzed data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, the federal government’s primary higher ed database, comparing incoming freshman classes in 2002 and 2018.

“I was stunned,” Klein said of the findings. “This is a radical level of change over just the last 16 years.”

Out-of-state students pay higher tuition, which incentivizes universities to go after this group, especially when state funding is cut, he said. Klein also looked at how the acceptance of more out-of-state students than in-state students affected state funding for those institutions.

“I find the states that have done more swapping have seen more declines in funding,” he said, likening it to a chicken-or-egg situation. “I don’t know who started the chicken and egg, but I’m concerned about where it’s going to end.”

Klein’s report, “The Great Student Swap”, describes this trend as the driver of increased college costs and student debt, but he doesn’t see academic benefits for students who opt to attend a flagship university out of state rather than in their home state.

Klein’s report, “The Great Student Swap”, describes this trend as the driver of increased college costs and student debt, but he doesn’t see academic benefits for students who opt to attend a flagship university out of state rather than in their home state.

“The premise behind college being a great investment is the delta between college and not going to college, not moving between relatively equivalent state flagship universities,” he said.

Not all flagship universities have seen large increases in the percentage of out-of-state students, according to the report. Those that have not include the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Delaware, the University of Maryland at College Park and the University of Idaho, among others.

North Carolina public colleges are required to have at least 82 percent of in-state students enrolled. Meanwhile, the University of Texas at Austin automatically admits in-state students who are in the top 6 percent of their graduating class. Klein points to such requirements as potential solutions that could limit the number of out-of-state students at public flagship institutions.

“Both of those rules have kept these institutions heavily in-state, and both of those institutions have maintained their level of selectivity and prestige,” he said.

Several other researchers have documented the increase in out-of-state enrollment at state universities over the years.

Ozan Jaquette, an assistant professor of higher education at the University of California, Los Angeles, outlined in a May 2017 report how public flagship universities were prioritizing admittance of affluent out-of-state students who are “less academically oriented” over qualified moderate- and low-income in-state students.

“Enrollment by moderate- and low-income students at public flagship state universities has stagnated because states have divested in public higher education,” Jaquette wrote.

He and other researchers have also analyzed the recruiting tactics of public universities and how the increase of out-of-state students affected in-state residents’ access to flagships.

More recently, Jaquette and Bradley Curs, a professor of education at the University of Missouri at Columbia, found that universities that had grown non-state-resident enrollment had hired more tenure-line faculty.

“Public universities are doing this because the state stopped funding them, and seems they’re using that money to hire faculty,” he said in an interview. “Hiring of faculty by public research universities was often on the basis of state funding and research funding. What we find in a paper that just came out is when you grow nonresident enrollment, that leads to much larger growth in tenure-line faculty, which is consistent with the idea that you’re substituting in the loss of state funding with out-of-state student tuition revenue.”

Jaquette said one positive outcome from the increased awareness about the trend is that state lawmakers have taken note. The University of California system reached a deal earlier this year with Governor Gavin Newsom and state lawmakers to increase access for more low-income and underrepresented in-state students in exchange for additional state funding.

Jaquette said state budget shortfalls led lawmakers to cut funding to research universities on the assumption that the institutions could raise funds in other ways.

“States that value public universities being for the state residents came to the conclusion—at least in California—that we can’t just cut appropriations to the flagships,” he said.

But he noted that in states where lawmakers aren’t keen on funding higher ed, the focus on out-of-state students will be “the new normal forever.”

Jaquette doesn’t expect continued increases in the percentages of out-of-state students at public flagships in the future, because “that big movement has happened,” and the number of affluent out-of-state students is relatively fixed.

He said colleges might try to increase the number of international students they enroll while other institutions, such as regional publics, will go after out-of-state students but not charge them more to boost enrollment.

“They need to put butts in seats because they’ve got excess enrollment capacity,” he said of the regional public institutions.