You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

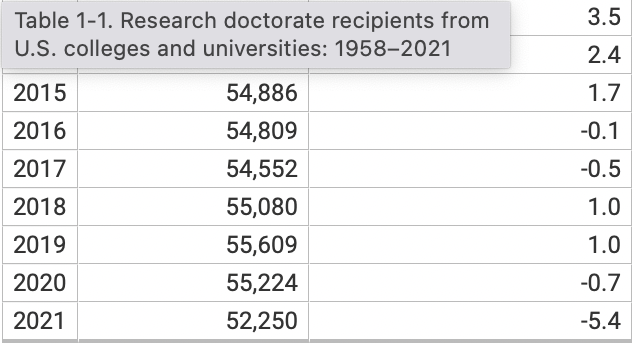

Survey of Earned Doctorates data show that the number of Ph.D.s conferred dropped 5.4 percent last year.

National Science Foundation

Newly available data from the National Science Foundation suggest that the first full year of the pandemic had a major, negative impact on graduate students’ ability to finish their Ph.D.s.

The NSF’s full Survey of Earned Doctorates report isn’t expected until December, and it will include fresh findings on how COVID-19 affected doctorate recipients’ graduate school experiences and postgraduation plans. But according to preliminary data out this week, the number of doctorates awarded in the U.S. dropped 5.4 percent between 2020 and 2021, the steepest decline ever for the NSF’s annual census of new Ph.D.s.

In numbers, 52,250 research doctorates were awarded across fields in 2021. That’s 2,974 fewer than in 2020.

Last year’s survey report showed a slight, 0.7 percent decline in Ph.D.s awarded between the 2019 and 2020 academic years. That was the first such dip since 2017, and experts said at the time that COVID-19 was probably a factor. But they really couldn’t say how big a factor, because the survey period of July 2019 to June 2020 covered just the first—albeit intense—few months of the pandemic.

The survey period for the forthcoming report ran from July 2020 to June 2021, a full year of the pandemic. So researchers more confidently link what turned out of be an unprecedented decline in Ph.D. production in 2021 to COVID-19.

Direct Impact

Kelly Kang, who manages the survey for the NSF’s National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, said the pandemic indeed “appears to be one of the factors in a significant decline in the number of doctorate recipients in 2021.” Graduates in the 2021 academic year were the first cohort “directly impacted by all the pandemic-related closures (classes, labs, etc.) which started in spring 2020,” she added via email.

Suzanne T. Ortega, president of the Council of Graduate Schools, which tracks graduate enrollment and degrees in its own annual survey, said Wednesday, “Not being able to conduct research in person due to COVID-19 could delay a doctoral student’s ability to complete their research and graduate. That may be what we are seeing in the NSF survey in the decline of doctorate recipients, and that students just need more time.”

CGS’s own data suggest that this is the case. In one fall 2020 council survey, 54 percent of doctoral student respondents said that they would need additional time to complete their degree due to the pandemic. In a separate survey the council fielded in late 2020, some 45 percent of underrepresented minority doctoral students said they would need more time to graduate.

The pandemic apparently affected students in some fields more than others in 2021 (although some fields were already experiencing longer-term declines in Ph.D.s). Degrees awarded in the life sciences fell 6 percent between 2020 and 2021, and by about 8 percent in the physical and earth sciences. Mathematics and computer science and engineering stayed relatively steady year over year. So did psychology and the social sciences broadly, with the exception of fields including anthropology, which dropped from 447 Ph.D.s awarded in 2020 to 400 in 2021. Given that anthropology as a field is small to begin with, this is a significant change.

Education degrees awarded fell 10 percent year over year. Humanities and arts degrees fell 16 percent. In foreign languages and literatures, specifically, the number of degrees conferred dropped from 564 in 2020 to 377 in 2021. In history, degrees conferred fell from 884 to 725. Letters: 1,389 to 1,192.

Robert B. Townsend, co-director of the Humanities Indicators project at the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, said the Ph.D. production decline “seems to be most acute in fields that rely heavily on research with other people or in other places.” Given the disruptions in this kind of work through the first year of the pandemic, "it stands to reason that those dissertations would be the disrupted and delayed.”

The “sharp drop" in humanities also stands out, Townsend said. “I think it has to be read against the sharp decline in academic jobs after the Great Recession. Many in the field have been wondering when the number of Ph.D.s would follow the jobs, and it started gradually 10 years ago, but adding the pandemic to the mix might have prompted more students to just give up. I wonder how many of the humanities Ph.D.s who had their work delayed by the pandemic will return to finish.”

Silver Lining on Job Placement?

The NSF’s survey also asks about graduates’ job placements: some 70 percent of new Ph.D.s in 2021 had definite commitments for work or postdoctoral training. This is actually a big increase since 2016, the most recent comparison period, when that figure was 62 percent. And that’s better news on job placements than some expected for pandemic-era Ph.D.s, given the widespread hiring freezes of 2020.

Looking at where these 2021 graduates planned to work, however, just 36 percent had secured jobs in academe. This is a serious drop-off from 2016, when that figure was 45 percent.

Where did those shut out of academe go instead? One possible answer is industry and business: in 2021, some 43 percent of new Ph.D.s had definite commitments in this sector, compared to 35 percent in 2016.

Debra Stewart, president emerita of the council and current senior fellow at NORC, a nonpartisan research center at the University of Chicago, said her own NSF-funded study of graduate deans in the summer of 2020 found that graduate schools were anticipating a notable decline in job placement for the coming year—something that now appears to be playing out for academic jobs, but not for graduates over all.

“This is both because universities were freezing job searches and because students were delaying graduation,” Stewart said. “Some of this was due to a delay in progress on their dissertation research because of lab closures and other COVID-related stoppages in research activity through 2020.”

Other areas of concern to deans in Stewart’s survey: that international students experienced both financial and travel restrictions, students with family responsibilities were especially challenged, and students with disabilities lost access to community services.