You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

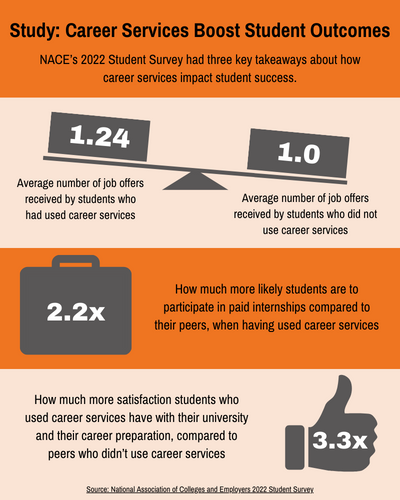

Students who engage with campus career centers receive more job offers and paid internships than their peers who do not, according to NACE research.

Getty / E+ / Marco VDM

Career readiness is a critical part of students’ postgraduate success in the workforce. The National Association of Colleges and Employers’ 2022 Student Survey found that graduating seniors who used career center services received more job offers on average, compared to their peers who did not.

While the advantages of career services are clear, higher education professionals must implement effective modeling and teaching for their students to navigate career readiness. NACE’s executive director, Shawn VanDerziel, sees the following strategies as key and effective measures to place students on the path to success.

1. Get students thinking about career prep early.

1. Get students thinking about career prep early.

Creating career-ready students should not start in the second semester of a student’s senior year, VanDerziel says.

While it can be intimidating or burdensome to a first-year student to consider life after college, starting small with different processes like a skills assessment can begin to drive career readiness, VanDerziel shares.

Before students step foot on campus, institutions should be “ensuring that career readiness is integrated into every step of a student’s experience from orientation, extracurricular activities, on-campus employment, implementing experiential education requirements, requiring career preparation courses and integrating career readiness into the curriculum,” he explains.

One approach: Kansas Wesleyan University matches each of its incoming students to a student success coach, who provides one-on-one first-year engagement with the Student Success Center’s resources prior to their work with an academic adviser.

2. Create career services champions across campus.

“Leadership of colleges [and] universities need to champion career services, and graduate employment outcomes as a top priority,” VanDerziel says. “Long gone are the days of just helping students with résumé reviews and just helping them set up on-campus interviews with employers.”

Career service professionals need help across the university to promote student outcomes, including adequate staffing, appropriate budgets and institutional support for programs and services. With this aid, they can lead and improve the work done, he adds.

One approach: at the College of William & Mary, career development is a key portion of the institution’s strategic plan, Vision 2026, and its office of Career Development and Professional Engagement has promoted experiential learning through scholarships and its campus partners.

Students who utilize career services are more likely to have a favorable impression of their educational experience, which translates to happy alumni, something all institutions strive for.

3. Translate coursework into career preparation.

In the spirit of making career readiness a university priority, faculty must be among those calling out skills development as it happens in the classroom.

Students learn deep information in their areas of study, but they also learn practical competencies that are useful in the world of work, and “faculty can help the students make those connections,” VanDerziel says. The website “What Can I Do With This Major?” is also an exploratory resource for students wondering how their classroom activities could be applied over a variety of careers.

It doesn’t require changing curriculum or creating additional assignments, but instead highlighting student’s communication skills, critical thinking, collaboration and project management as they appear in the classroom.

However, a for-credit or no-credit class offering is also a good strategy to engage students’ career-preparation skills, VanDerziel adds.

One approach: Nazareth College in New York offers a one-credit Job Search and Professional Preparation Communication course to develop résumés, cover letters, networking skills and their online presence and practice interviewing. The students also engage with the college’s alumni and professional network.

4. Hone the development of résumé skills across activities.

Employers point to a skills gap in the postgraduate workforce, particularly in a post-pandemic world. But VanDerziel and NACE disagree with the assessment that students lack the necessary skills.

“It’s not a great skills gap. There’s a communications gap,” VanDerziel says. Students have the needed skills but lack the awareness or knowledge to articulate those talents in a résumé or cover letter, he argues.

Varsity athletes may have experience as a team captain, but they have no way to define the soft skills required for the role, as an example. Instead, community members should talk about the skills learning in the activity, sports in this example and how that applies to future work.

“What we need to do as a campus community is to be more direct with students to help them to make those connections,” VanDerziel says.

One approach: the University of Tampa has a résumé-writing guide that outlines basic content and formatting for students, including how to select keywords for a job description and how to create résumé bullet points.

Seeking stories from campus leaders, faculty members and staff for our new Student Success focus. Share here.