You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

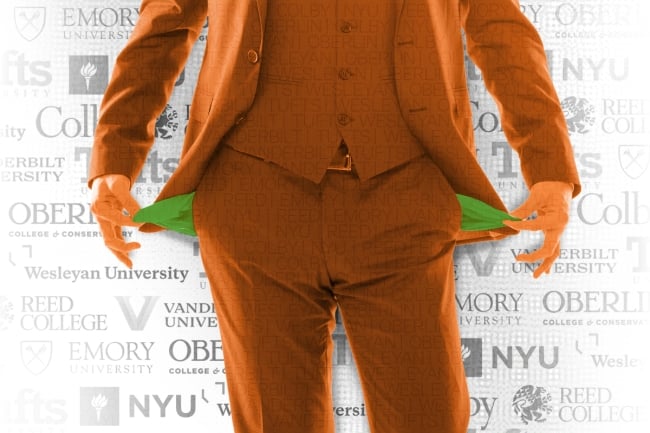

A recent report concludes that class-conscious admissions preferences would be too costly for most selective colleges. Others say it’s a question of priorities.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images

Even before the Supreme Court handed down its decision banning affirmative action in this summer’s Students for Fair Admissions case, selective institutions began weighing a litany of legal strategies for maintaining racial diversity, from shifting recruitment targets to retooling application questions.

Some have suggested a class-based alternative to affirmative action. Advocates say that because many lower-income students are Black and brown, using class as a proxy would undercut the negative effects of the ruling on racial diversity. It would help highly selective colleges improve their abysmal socioeconomic diversity, too.

But a recent study from the Brookings Institution that simulated the cost and effect of adopting socioeconomic preferences in admissions found that while institutions could maintain pre-SFFA levels of diversity, it would be both “considerably less efficient” in creating a diverse student body and extremely costly. While a handful of colleges are financially flush enough to make the investment, the study concludes that for most, the price tag would be an “insurmountable hurdle.”

Moderately to highly selective colleges would need to more than triple their current financial aid budgets to support a class-conscious admissions preference that could also maintain racial diversity, the study found. That’s a tall order considering that just meeting the full financial need of current students would require most colleges to double their financial aid budgets.

“If selective colleges adopted class-based affirmative action policies aggressive enough to maintain racial diversity, many institutions would struggle to find the necessary funds to support more low-income students without threatening their academic mission,” the study concludes.

Philip Levine, an economics professor at Wellesley College and one of the study’s authors, said that if colleges can’t support lower-income students with sufficient financial aid to make their degrees affordable, admitting them could prove an empty gesture.

“It’s difficult not to support this philosophically, because selective colleges really do have a major socioeconomic disparity problem,” he said. “But this is a resource issue … The financial aid system is already woefully inadequate. It’s just a matter of crunching the numbers.”

Many advocates of a socioeconomic approach to diversity say the price is more than worth the outcome and that well-resourced institutions bemoaning the end of race-conscious admissions should put their money where their mouths are.

Richard Kahlenberg, nonresident scholar at Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce and a longtime advocate for class-based admissions preferences, said selective colleges’ reluctance to support more low-income students “betrays a certain mind-set” that undermines their ostensible missions as engines of socioeconomic mobility.

“The dirty secret about selective colleges is that they can get even more diversity without affirmative action than they even could through it—not just racial diversity but class diversity,” Kahlenberg said. “It’s just more expensive. But that’s a question of values and priorities, not feasibility.”

Cost Issue or ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’?

Catharine Bond Hill was president of Vassar College from 2006 to 2016. During her tenure, she championed a return to the college’s former need-blind policy, advocating for increasing financial aid to meet 100 percent of student need.

Shortly after she proposed the plan, however, the 2008 financial crisis hit, and she said the college had to make difficult cuts elsewhere to move ahead. But backed by supporters, Hill held fast, and the policy ultimately had a real effect on the highly selective liberal arts college: applications from students of color doubled in nine years, and the median family income for admitted students dropped by over $20,000.

The college remains need-blind in the admission process for U.S. citizens and permanent residents, and meets 100 percent of demonstrated need for all admitted students. Still, Hill said some worried that investing so much in aid would make Vassar less competitive among its peers, hampering its ability to hire big-name faculty or beef up student amenities. (This paragraph has been updated to correct an erroneous statement that Vassar's need-blind policy had changed.)

“Princeton, for example, has enough money to do something like this without worrying about a competitive disadvantage,” said Hill, who is now managing director of the education consulting firm Ithaka S+R. “But as you go further down, schools are always trying to move up in selectivity, and [they] worry that the more they spend on need-based aid, the less they’ll have to hire extraordinary faculty or build state-of-the-art facilities.

“It’s part of the way the competitive market works,” she added. “And it’s very hard for schools themselves to solve that problem.”

Levine said that’s part of the case he hoped to make with the Brookings report: that while the admissions policies of selective colleges could better prioritize low-income students, the onus to fund this public good should be primarily shouldered by public institutions—namely state and federal governments. They could tie tax subsidies to the proportion of low-income students at private colleges, for instance, or expand student aid grants and administer them on a sliding scale according to an institution’s socioeconomic diversity.

“If we can increase the ability to bring in lower-income students, particularly into more highly ranked institutions, that will do a tremendous amount of social good,” Levine said. “Somewhere along the line, more public money will need to be made available if we decide that we want to address this problem.”

Kahlenberg agrees that the financial aid resource crunch is a strong argument for better federal and state student aid, which has lagged well behind inflation for years. But that doesn’t mean the upper tiers of financially flush colleges can’t do their part, too.

“Institutions commit money to things they really value. Do they not value socioeconomic diversity?” he said. “I don’t think it’s an unreasonable ask. The [Brookings report] feels like a defense that a provost would offer. It’s really letting colleges off the hook.”

Hill said she believes colleges should support more low-income students but understands the concerns about greatly expanding financial aid budgets. For moderately selective private colleges in fierce competition with one another, there’s little incentive to make a bold commitment on one’s own.

“It’s a bit of a prisoner’s dilemma,” she said. “Either everyone does it or no one does.”

An Inefficient Alternative

The Brookings study found that while considering class in admissions decisions would be a more efficient diversity booster than some leading race-neutral alternatives—such as giving preference to first-generation students—it’s still far less effective than race-conscious admissions has been.

“The advantage of old-fashioned affirmative action is that it was very efficient in its targeting,” Levine said. “Class-based affirmative action would work as an alternative because income and race are correlated. But they’re not perfectly correlated—far from it, in fact.”

The most selective institutions—with their multibillion-dollar endowments—may be best positioned to advance economic equity in higher education and beyond; research shows that they offer underprivileged students the best chance of dramatically boosting their socioeconomic status. But the problem runs deeper than that.

“The issue of socioeconomic access to higher education is much broader than at just the most elite institutions,” Levine said. “Thirty colleges can’t fix this.”

Hill believes that committing to broadly popular policies of supporting more low-income students could help selective colleges do more than just maintain their racial diversity. It could bolster higher ed’s place in the public imagination, currently at an all-time low across the political spectrum.

“Elite colleges are in the crosshairs of both the left and right at the moment. That’s not a good place to be, but in many ways they deserve to be there,” she said. “They have not stepped up to fulfill the social mobility mission of higher ed. If they did, they might have more allies.”

For Kahlenberg, framing the concept of class-based affirmative action as an alternative to race-conscious admissions misses the point; expressing a preference for low-income students would help rectify a deep fissure between the purported mission of American higher education and the reality on campuses, he said, and adopting such policies makes sense regardless of the Supreme Court’s decision.

But he also believes the 2023 Supreme Court decision represents a critical juncture for higher ed, one that requires highly selective colleges to make a bold ideological and financial commitment to meet the moment.

“This is a call to action and should be seen as such, instead of hand-wringing about cost and putting a depressant on these efforts,” he said. “We’re at a crisis point right now; we cannot allow highly selective colleges to resegregate.”