You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A new report from the American Psychological Association explores the barriers faculty members of color face in gaining tenure and promotion.

SDI Productions/Getty Images

A new report by the American Psychological Association argues that the diversity of the professoriate isn’t keeping up with the increasing racial and ethnic diversity of the United States and that the lag in progress has far-reaching implications in academe and beyond.

Despite sweeping declarations of commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion from a litany of institutions over the last several years, the findings published today by a task force of the association illustrate the barriers to tenure, promotion and retention that psychology professors of color still face.

The task force was made up of psychology professors from colleges and universities across the country who spent a year, from 2021 to 2022, reviewing numerous quantitative and qualitative studies to inform their recommendations on how to address issues such as unrecognized mentorship, disproportionate expectations of committee work and biased views of certain research topics. Some of those recommendations for making tenure evaluations more inclusive include addressing biases in student evaluations and giving more weight to the service activities professors perform.

“This is not just an issue for psychology, this is an issue for all of academia,” said Mitch Prinstein, the APA’s chief science officer, who came up with the idea for the task force. “We hope this report helps other disciplines think about ways we can make the entire academy a place that recognizes a variety of contributions and celebrates diversity and updates its systems to reflect the more diverse world we live in now.”

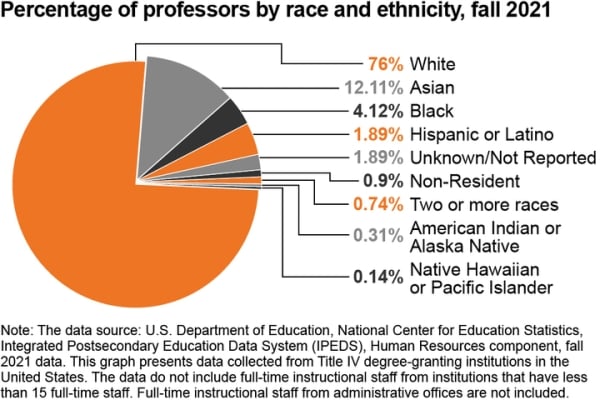

The percentage of white people in the United States declined from 79.4 percent in 1980 to 57.8 percent in 2020, according to the report, which used an analysis of U.S. Census data to gather those numbers. At the same time, the percentage of white professors far outnumbers faculty members of color, and that divide widens with each step toward becoming a full professor.

While the report did not offer data specific to psychology professors, it used U.S. Department of Education data to provide an overview of where diversity in the professoriate stands over all. As of fall 2021, 60.5 percent of assistant professors were white. Nearly 71 percent of those at the associate professor level were white, and 76 percent at the full professor level were white.

American Psychological Association's Task Force Report on Promotion, Tenure and Retention of Faculty of Color in Psychology

‘Invisible Labor’

The drop-off of faculty of color on the tenure track happens in part because of the demands of “invisible labor” performed by—and sometimes informally required of—faculty of color across all disciplines.

That’s something Michael Cunningham, who is now a professor of psychology and associate provost in the Office of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies at Tulane University, experienced when he started his job as a new professor in 1996. At that time, he was the first Black professor his department had ever employed.

“Students who were not even psychology majors were dropping in for advice, because Black students wanted to talk to a Black professor,” said Cunningham, who provided feedback for the report. “Unless your department understands that and counts that as part of your service, you end up advising more students than your colleagues who are not in minoritized groups, and you tend to be an advocate for students because you need to step up and say something.”

Cunningham said new professors at his institution are not typically asked to do heavy committee work so they can focus their time on the research and publications that are critical to promotion. However, during his first semester at Tulane, he was put on a technology committee, which had nothing to do with his scholarly expertise.

“I finally said that if they want me on this committee because they want it to be more diverse, then perhaps they need to have a more diverse pool of faculty members. I can’t be on all of these committees,” Cunningham said. “They want committees to have voices and representation from different groups, but if you don’t have that population there, the minoritized faculty and women end up doing more service.”

And when mentoring and committee work aren’t valued as heavily as scholarly publications in tenure decisions, it can lead to burnout and push faculty members of color to look for jobs outside the academy.

“If you’re a licensed psychologist, you can easily go into practice and have many more opportunities out there,” Cunningham said. To combat that exodus, “institutions need to make sure that [tenure] process is fair,” which includes protecting the professors’ time.

‘Hidden Curriculum of Tenure’

Margarita Azmitia, a psychology professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and co-chair of the task force, said knowing that this time has to be protected if a new professor wants to get promoted is part of the “hidden curriculum of tenure.”

That’s why the report calls for more transparency in the expectations of tenure-review committees.

“Faculty of color are often not from families of professors,” said Azmitia, who is originally from Guatemala. “One of our recommendations is that all incoming faculty of color get assigned a mentor.”

She said those mentors should get credit for mentoring colleagues to avoid falling into the invisible labor trap.

“When you’re a faculty member of color, it’s just expected that you’d love to do it, and we do,” she said. But it won’t work “if you don’t create support and recompenses, like course relief, that fosters what you’re trying to do in terms of mentoring, support and teaching people. It won’t work if it’s not mutual and if it’s not recognized.”

Research Deficit

The type of psychological research—and where it gets published—also weighs heavy in tenure and promotion decisions. But as the report notes, research that focuses on underrepresented communities isn’t always given the same value as research focused on white populations.

A 2020 article in the peer-reviewed journal Perspectives on Psychological Science found that over the past 50 years, “psychological publications that highlight race have been rare” and that “most publications have been edited by White editors, under which there have been significantly fewer publications that highlight race.”

“In most areas of psychology, most of the research has focused on the majority—privileged white children, adolescents and adults—so we don’t have sufficient theories that focus on minoritized people,” Azmitia said. “The U.S. is diversifying, and what does it mean when we don’t understand or know or have theories about their experiences?”

Tiffany Yip, a psychology professor at Fordham University who reviewed the report, said that’s a problem that starts with types of projects that receive the most grant funding.

Yip, who has served on grant-review panels, said, “There are places where work is seen as not as important if it focuses on statistical minority groups.” And if reviewers are using that “statistical generalization as a criteria for how important the work is, then it will never get funded, because minoritized people are in the statistical minority.”

In addition to funding inequities being barriers for faculty of color trying to publish research focused on minority populations, it also sends a message to undergraduates who may be considering a career in the field of psychology.

“Psychology is an incredibly popular major at most institutions. And we already know that the American population under 18 is primarily people of color,” Yip said. “The reality is that they’re already in the numerical majority. So, if they’re not seeing themselves reflected in the classroom through the faculty or class materials, it’s really going to make that work less relevant to their lived experiences.”

Biases in Evaluations

Yet another barrier to tenure and promotion, the report notes, are biases in teaching evaluations.

“There are studies that show when faculty of color have student evaluations, the open-ended responses are attacking their race and ethnicity as opposed to talking about the content of the course,” said Michelle Martin, co-chair of the task force and founding director of the Center for Innovation in Health Equity Research at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. For example, “We know male students prefer male professors,” she said. To that point, “if the university believes student evaluations of teaching are important,” it should “provide a context,” such as the racial and gender makeup of the students writing the reviews.

Without that context, repeated instances of biased evaluations can create “racial fatigue” for faculty of color, which is “why many faculty decide to leave.”

Martin said these challenges can be overcome “by taking a hard look at promotion and tenure criteria and seeing where implicit bias can creep in and change those things.”

Removing expectations of subjective “collegiality,” for example, is another solution, because that concept is subjective.

“Sometimes it suggests that if you’re a faculty member of color and you raise an issue that you’re not a good colleague,” she said.

Martin made clear, however, that she and her report co-authors aren’t pushing to “throw out metrics that exist” to evaluate promotion and tenure. They instead want the academy to “be mindful of the limitations of those metrics and broaden the metrics that are used so they can be more inclusive.”

The end goal isn’t to make the tenure process any less rigorous but instead to give credit for contributions that aren’t always recognized.

“We still want high-quality, excellent work,” Martin said. “But that comes in a lot of forms that are not currently reflected in the academy.”