You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A street sweeper in Kunshan, China, walks past a sign announcing Duke University’s branch campus there in 2011. After a rush of interest in the 2010s, U.S. branch campuses in China are facing an uncertain future.

In Pictures Ltd./Corbis via Getty Images

When Duke University opened its campus in Kunshan, China, almost a decade ago, it was following on the heels of a movement of institutions eager to establish beachheads in the country during the political and economic détente of the mid-2010s.

But at a meeting with faculty and staff in November, Duke president Vincent Price said the institution’s leaders would “have to be clear-eyed” when considering whether to continue their contract with local partner institution Wuhan University when it comes up for renewal in 2027.

Price said he was proud of Duke Kunshan and happy that Duke could be a “lifeboat” for students who wanted to come to America. But between rising geopolitical tensions and the gauntlet of managing a Chinese presence through the pandemic, operating the campus had become an undeniably tall order.

“The world is conspiring to make that kind of a project really hard these days,” he said.

Price’s ambivalence about Duke Kunshan is not isolated. There is broad consensus in the American higher education world that the challenges of operating a branch campus in China are mounting, and they will only grow more difficult in the years ahead. But not everyone agrees on whether those obstacles will become insurmountable.

Philip Altbach, director emeritus of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College, said he has little confidence in the staying power of U.S. branch campuses in China, but that institutions’ investments make them difficult to abandon.

“The reputational and economic downside is quite significant in that deteriorating local situation relating to academic freedom, and the deteriorating geopolitical problems,” he said. “But places like NYU [Shanghai] have been there for a decade, and have invested a lot in those campuses, so what are you going to do? They’re going to have to figure it out.”

Christopher Simmons, Duke’s associate vice president of government relations, told Inside Higher Ed that Price was merely voicing concerns and that the university remained committed to the partnership.

“Of course, we’re doing our due diligence and always paying attention to issues that may make us re-evaluate some of those agreements, but also the opportunities that still exist in enhancing those relationships,” he said. “These are not easy ventures. They’re complicated. But we’re incredibly proud of the achievements that we’ve had helping to establish DKU.”

Denis Simon, who ran Duke Kunshan as its executive vice chancellor from 2015 to 2020, doesn’t have the same confidence in the institution’s future. He described the job as “extremely difficult” and said that in order for the venture to be feasible and successful, Duke would have to “make some major changes to the way it is managing the project.”

“Running a campus in China is becoming increasingly challenging, because of the changing bilateral relationship, the changing political environment in China, issues of academic freedom, the chaos of the pandemic,” said Simon, now a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Kenan-Flagler Business School. “Most universities don’t realize the tremendous investment they must make on their own campus in order to ensure they can effectively manage one of these joint venture universities, which are only going to get more complex.”

Stateside, those challenges include navigating a political environment increasingly wary of Chinese international partnerships, both at the state and national levels.

“Domestic political discourse is increasingly hostile to internationalization in general, and to operations in China in particular,” said Kyle Long, founder and director of Global American Higher Education, a coalition of researchers studying American institutions abroad. “The question I have is, do [college] presidents have the will to fight these battles? I’m not sure. Internationalization often finds itself at the bottom of the list, if it’s on the list at all.”

‘Clear-Eyed’ in Murky Waters

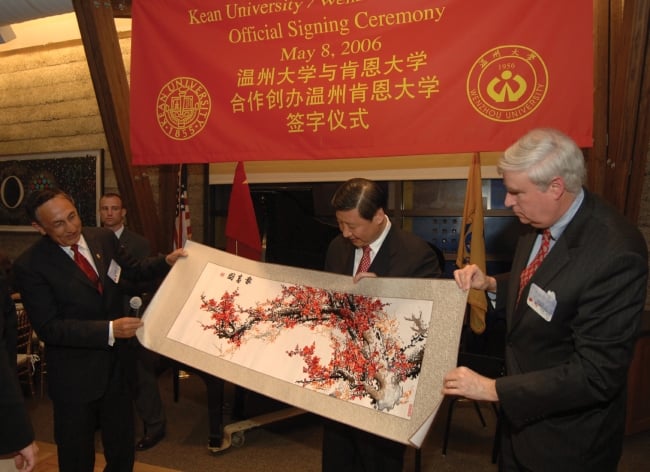

In May of 2006, Kean University in Union, N.J., had an unlikely visitor: future Chinese president Xi Jinping.

At the time he was the Communist Party secretary of Zhejiang Province, seven years away from becoming the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong. In Union, Xi signed an agreement with Dawood Farahi, Kean’s then president, who retired in 2020, to establish what would become the first Chinese branch campus for a public American institution.

Six years later, just as Xi was beginning his first term as general secretary, Wenzhou-Kean University opened in a small satellite city of Shanghai in partnership with the local Wenzhou University.

Former Kean president Dawood Farahi (far left) with Xi Jinping (center) at Kean University in 2006. During Xi’s visit, they inked an agreement to establish Wenzhou-Kean University, a branch campus in China.

Kean University

Xi was in New Jersey as part of a broad effort by the Chinese Communist Party to facilitate exchange with the U.S. and keep Sino-American relations on the up and up. Geopolitical tensions thawed considerably after President Clinton normalized trade relations with the country in 2000, and cultural and intellectual exchange was flourishing, facilitated in part by institutions of higher education. Chinese students quickly became the largest source of a growing pool of international applicants to American universities, and the burgeoning internationalization movement had many college leaders eyeing China as a logical destination for their bases abroad.

But China’s political pendulum has since swung back toward isolationism and conflict with the West, and Xi has cultivated a very different perspective on Sino-American exchange than he showed in 2006 when he visited Kean. The pace of that change has only continued to gain steam; just last month China enacted a sweeping foreign relations law aimed at curbing Western influence in the country, and the U.S. warned citizens against visiting. The deterioration of diplomatic relations, domestic American political pressures, paranoia about academic spies, tighter censorship enforcement and increasingly anti-Western messaging in China are all threats to academic partnerships between the two countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic only added to those woes. Beijing’s strict zero-COVID policy meant that any American faculty, students or administrators who stayed in the country were often subject to long periods of forced isolation and even after that had limited geographic mobility.

Beyond the logistical nightmare, Chinese authorities’ brutal treatment of Chinese student protesters during demonstrations against the lockdown policies shocked and angered many American students and faculty—and threw the ethics of doing business with those campuses into question.

“I think it probably did leave a bad taste in a lot of institutions’ mouths,” Long said. “It’s a big risk, not just PR-wise but financially, especially where real estate is involved and they can’t fill it and are just bleeding money.”

Equal Partners or Franchisees?

The first American branch campus in China since the Cultural Revolution was Johns Hopkins–Nanjing in 1986. But Long, who is also the senior director of organizational strategy and change at Northwestern University, said American institutions began exploring partnerships in China in earnest in the early 2000s, at the same time the branch-campus model took off around the world. He added that their growth is inextricably linked to the explosion in Chinese international student enrollment in the U.S.

“You can’t tell the story of the boom of American campuses in China without also recognizing that it’s occurring in lockstep with Chinese enrollments in stateside U.S. universities,” he said.

China has by far the most active American higher ed programs and institutions of any foreign country. According to the Global American Higher Education database, there are 59 American institutions operating in China; the second most active country is the United Arab Emirates, with only 12.

The vast majority of those are either jointly operated programs like Hopkins-Nanjing, which make up 23 percent of American higher ed ventures in China, or what are known as microcampuses, like Arizona State University’s partnerships in Xi’an, Zhengzhou and Qingdao, which focus on specific programs and make up nearly half of the country’s American higher ed presence.

None of these are quite branch campuses, though, according to Long, because Chinese law requires any foreign academic institution to operate in partnership with a Chinese one. Those partners—East China Normal University for NYU Shanghai, Wuhan University for Duke Kunshan, and so on—usually lay out much of the capital needed to construct a new campus and also appoint administrators, often CCP officials, to help run the institution alongside American counterparts.

Former NYU president John Sexton (left) and East China Normal University president Yu Lizhong at the opening ceremony for NYU Shanghai in 2011.

Visual China Group via Getty Images

That creates a special set of concerns around academic freedom. In 2019 NYU Shanghai came under fire for adding a “civic education” course to its curriculum at the behest of government officials, for example. A university spokesperson told Vice News that the course was a requirement for all Chinese national students and international students were not required to take it, but the concerns remain.

“There is a subterranean governing structure that operates at DKU and other branch campuses, that involves the Chinese Communist Party officials, local officials and documentation that is not shared with the foreign side,” Simon said. “Unless you really understand that communication system, you don’t really know what’s going on.”

One former lecturer at Wenzhou-Kean, who wishes to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal, said there were times when they felt intimidated by Chinese administrators for broaching taboo subjects. They said all their colleagues were given a list of topics that were off-limits in class, including many areas historically repressed by the CCP, like the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, Hong Kong’s political turbulence, the detainment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang Province, and Taiwan’s independence.

They recalled an incident when they were teaching about Taiwan, which Beijing considers part of China, and mentioned that while it was close to Wenzhou, it was not in the same category as many other parts of China that Wenzhou-Kean students came from—the instructor said they merely meant that it was an island separate from the mainland, not an independent nation. Nevertheless, they were called into the office of the vice chancellor, a CCP member, and reprimanded.

“It was intimidating. We have no academic freedom, basically, and there’s a lot of self-censorship that goes on,” they said. “It’s a very strange world, because everybody is quiet and everybody’s scared, including the teachers. Especially the teachers.”

They said they thought the high standards for academic freedom enforced by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, which accredits Kean and, by extension, Wenzhou-Kean, would protect faculty from that kind of repression. They were shocked when it didn’t appear to matter.

Another former Wenzhou-Kean professor who also requested anonymity said there was, in effect, no shared governance or accountability measures available to faculty.

“[Chinese administrators] dealt with us in a very paternalistic and condescending way, as if we were their children,” the second professor said. “That results in zero faculty government structure. That’s a huge cultural rub, because American faculty are used to having a voice in the running of their institution.”

The first Wenzhou-Kean lecturer said that while in theory the university was a partnership with Kean, the New Jersey campus didn’t have the resources or the will to run it as equal partners with the Chinese, who they said dominated the administration.

“The partnership is almost like a McDonald’s franchise or something,” they said. “The IP is American, so are the syllabi and textbooks and many of the professors. But the production is Chinese.”

Karen Smith, Kean’s vice president of university relations, said the university “maintains full academic control” of Wenzhou-Kean and is committed to ensuring its faculty’s unchallenged academic freedom.

“Academic Affairs at WKU is managed by Kean USA with the same values and commitment to academic freedom as exists on any Kean campus,” she wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “The curriculum, accreditation and academic standards continue to be based on those at Kean University.”

Altbach said that while the franchise model isn’t the rule for U.S. campuses in China, it’s much more common than it ought to be.

“The name-brand, top universities like NYU and Duke are not going to franchise away control over their educational programs or what they do overseas, because the public relations downside of that sort of thing is too high,” Altbach said. “But there are many, many, many non–brand name institutions, Western ones, that have these franchise arrangements.”

In Altbach’s perspective, the variegated landscape of higher ed partnerships in China contributes to the challenges of running them responsibly. Between the microcampuses and the joint partnerships, he said, there’s a wide array of initiatives that can veer into profit-driven, corruptible ventures, doling out American degrees without doing their due diligence in ensuring high quality or enforcing academic freedom.

“This is a huge industry. It’s varied and out of control, and I think that’s a problem, frankly,” he said. “What are these institutions doing, and why are they doing it? The reason is to make money, generally speaking.”

Approaching a Cost-Benefit Tipping Point

Altbach said he doesn’t think investing in physical initiatives in China is a wise move right now, and that whatever they’re saying publicly, U.S. institutions understand that.

“The bloom is off the rose when it comes to China,” he said.

Long said the rapid boost in the quality of Chinese institutions has also made American higher education partnerships less relevant, and Xi Jinping’s general policy of Chinese exceptionalism makes American institutions potential targets. In 2018, the Chinese ministry of education terminated hundreds of foreign academic partnerships, including degree programs at many American branch campuses, citing poor quality and administrative difficulties.

Like Altbach, Long predicts more U.S. institutions, especially for-profit ones, will shutter their ventures in China in the coming years. But he’s more bullish about the future of American higher education in China broadly and believes the institutions that are invested for reasons beyond revenue—like pursuing research relationships, recruiting talent or encouraging intellectual exchange—will weather the storm.

Despite the challenges, U.S. institutions are continuing to invest in projects in China. The most recent is Portland State University’s partnership with Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, which opened last year. The Juilliard School’s campus in Tianjin, a major undertaking and one of the few comprehensive branch campuses in the country, opened in 2020.

Juilliard’s new campus in Tianjin, China, in 2020.

VCG via Getty Images

Institutions that have already invested years of effort into their campuses aren’t cutting their losses just yet, either. Simmons said Duke was moving forward with a five-year plan to expand the campus in Kunshan. Smith said Wenzhou-Kean “continues to expand” under current university president Lamont Repollet. And despite being unfinished for the start of the spring semester, construction on NYU Shanghai’s new campus was completed in March, just in time for the celebration of the partnership’s 10th anniversary.

Long hopes the leaders who are committed to their ventures will remain so, not in spite of the widening gap between China and the U.S. but because of it.

“We should not discount the contributions of these branch campuses to public diplomacy. The more of these we have, the harder it’s going to be for America and China to have a really contentious relationship,” he said. “That doesn’t mean it’s uncomplicated. To the contrary—it’s considerably more complicated now. But to me, that’s all the more reason to do it.”

But even for those who believe in the mission of cross-cultural exchange, the difficulties of bringing an American academic experience to China can be overwhelming. The anonymous former Wenzhou-Kean lecturer who was reprimanded by the vice chancellor moved away from the country two years ago, after enduring the first year of the pandemic there, and never returned. They said many others did the same and either tried teaching remotely from more liberal countries or let their contracts lapse.

Recently, the lecturer was invited back to teach at Wenzhou-Kean. While they want to be part of the partnership’s mission of bridging cultural gaps, they said their experience made it difficult to return.

“I left because I couldn’t handle it anymore,” they said. “And I know I’m not the only one.”