You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

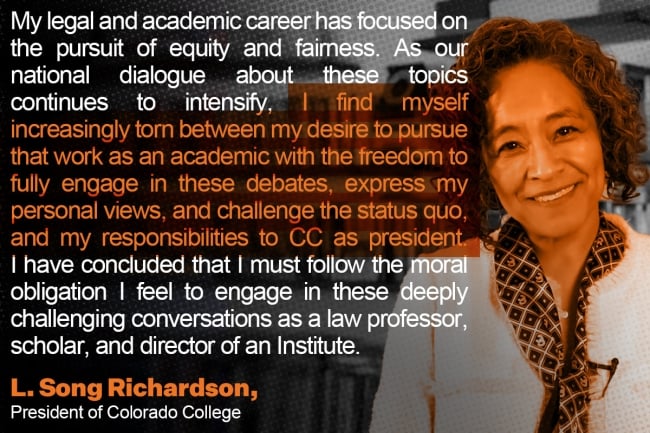

L. Song Richardson is resigning as president of Colorado College.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Colorado College

After three years as president of Colorado College, L. Song Richardson is stepping down to focus on scholarly work. She noted in her resignation announcement last week that she feels constrained by the position and wants to fully engage in robust debate about hot-button national social issues.

The move comes at a tumultuous time for higher education. Institutions across the country have been caught in the political crosshairs over diversity, equity and inclusion efforts and student protests over the Israel-Hamas war, with presidents often bearing the brunt of such attacks. At the same time, public confidence in the sector has declined sharply over concerns about cost and student outcomes.

Richardson, a celebrated legal scholar—whom The Washington Post once projected as a long-shot Supreme Court nominee—plans to return to the University of California, Irvine, where she previously served as dean of the School of Law, to launch a new institute focused on equity, opportunity and leadership, according to her resignation announcement. An expert on race and politics, Richardson, who is Black and Korean, is seeking to fully engage on these issues at a time when discussions about DEI have taken center stage in American politics amid the recent fall of affirmative action in admissions.

To Speak or Not to Speak?

Praise poured in when Richardson was hired as president of Colorado College in late 2020. Supporters pointed to her legal acumen, scholarship, charisma and dedication to students.

Now she’s leaving at the end of June.

In her announcement, Richardson wrote that as the national dialogue around “equity and fairness” has intensified, she has felt “increasingly torn between my desire to pursue that work as an academic with the freedom to fully engage in these debates, express my personal views, and challenge the status quo” and her responsibilities as president of the college.

In an interview with Inside Higher Ed, she acknowledged that she felt constrained by the presidency, even at a progressive private institution with a supportive governing board and community.

“I do think it is challenging to speak in one’s personal voice, when, from my own perspective, the role of the president is to speak on behalf of the institution,” Richardson said.

Richardson pointed to the end of affirmative action as an example of a topic she isn’t able to engage publicly on, though she did release a statement following the Supreme Court’s ruling banning the practice last June, emphasizing Colorado College’s commitment to diversity.

“There are many things that I can talk about in my role as president that are consistent with the things that we are trying to do as we move forward in this higher ed space. And then there are things that if I were an academic, as a law professor and scholar, I could speak more robustly about,” Richardson said. “For instance, I’m a scholar of race, equity and inclusion. I have a lot of deep knowledge, based on my own scholarship, about the issues that are being debated today. And because of my role as president, I won’t speak as I would if I were an academic.”

Richardson also said she doesn’t want her own views to drive the conversation on campus.

As president, she’s been more focused on creating “spaces for people to engage in those debates,” she said. She’s worried that if “I come down on one side, personally, based on my own research and scholarship and feelings about the affirmative action decision, it might stifle the type of conversation I want our community and students and staff and faculty to have.”

The demands of the presidency also prevent her from digging into the issues as deeply as she could if she were solely a faculty member, she said.

Pressures of the Presidency

Richardson’s resignation comes at a time when the role of the college president has grown increasingly fraught with business challenges—as many colleges struggle to generate revenue—as well as political land mines.

Presidents are being asked to guide their institutions through the choppy waters of sluggish enrollment and demographic shifts, even as they deal with increased operating costs and wage pressures. At the same time, culture war proxy battles seem to be intensifying on campuses in the wake of Hamas’s Oct. 7 terrorist attack on Israel, which triggered a bloody war in Gaza that has left tens of thousands of civilians dead and destroyed scant resources.

Student responses, particularly those calling for just treatment of the Palestinian people or criticizing Israel for its use of deadly force, have galvanized alumni, donors and politicians, prompting the deployment of so-called doxing trucks against students and faculty who support the Palestinian cause and numerous investigations into alleged antisemitism.

It’s impossible for presidents to please all their constituents, and sometimes they wind up satisfying none. When college leaders released a flurry of statements after the Hamas attack in October, they sparked furious blowback on some campuses. Critics accused them of failing to adequately acknowledge one side of the conflict or the other, and of going too far—or not far enough—in issuing remarks.

Amid sweeping charges of antisemitism on U.S. campuses, the presidents of Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology appeared before Congress in a disastrous December hearing that featured multiple missteps, including all three equivocating on questions about hypothetical calls for genocide. Two of the leaders—Claudine Gay of Harvard and Liz Magill of Penn—resigned shortly thereafter. (Plagiarism allegations exacerbated the pressure on Gay to resign.)

In the wake of the congressional hearing, some have called on college presidents to stay silent on political issues. Last year Utah governor Spencer Cox, a Republican, cautioned presidents at the state’s public institutions to avoid taking positions on political topics.

“I do not care what your position is on Israel and Palestine. I don’t,” Cox told college leaders at a December news conference, according to the local Salt Lake Tribune. “I don’t care what your position is on Roe v. Wade. We don’t need our institutions to take a position on those things.”

And last week the Academic Freedom Alliance, Heterodox Academy and the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression shared an open letter to university trustees and regents that raised concerns about institutional political statements, freedom of speech and open inquiry.

“In recent years, colleges and universities have increasingly weighed in on social and political issues. This has led our institutions of higher education to become politicized and has created an untenable situation whereby they are expected to weigh in on all social and political issues,” read the letter, which ends in a call for governing boards to establish institutional neutrality policies.

Presidents as Moral Leaders

In some ways, such calls reflect the changing nature of the presidency today. Given the business challenges of higher education and declining public confidence in the sector, presidents are increasingly expected to be crisis managers and fundraisers, with the historical role of college presidents as moral leaders seemingly on the decline.

But some still believe there’s a place—and a need—for college presidents to model values as part of their leadership approach.

Michael Roth, president of Wesleyan University, argued in an op-ed published after the congressional hearing in December that his counterparts “failed the test of good sense and decency.” In Roth’s view, presidents must “speak up on the issues of the day when they are relevant to the core mission of our institutions” and defend academic freedom when attacked.

Pat McGuire, the long-serving and notoriously outspoken president of Trinity Washington University, recalled a number of “intellectual giants”—such as Father Theodore Hesburgh at the University of Notre Dame; Clark Kerr at the University of California, Berkeley; and Hanna Holborn Gray of the University of Chicago—as “presidential exemplars.”

“But heading toward the middle of the 21st Century, we are hard-pressed to find presidents of such moral and intellectual stature; instead, we have many perfectly competent managers, some remarkable rainmakers for their institutions, and a few notable innovators—but no real national exemplars of a college president as a leader in society. We are expected to keep our businesses afloat, improve our competitive posture within the peer group, and otherwise stay out of trouble both institutionally and personally,” she said by email. “Headlines are verboten!”

McGuire also believes governing boards, broadly speaking, are looking to fill presidential posts not with principled role models but with business leaders who can manage complex institutions and woo donors. In “these fraught political times,” boards are intent on not generating controversy, she added.

The Reverend Robert M. Franklin Jr., a former president of Morehouse College and current professor of moral leadership at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology, said by email that “moral leaders help others to become better versions of themselves”—which is also “the purpose of education.” That gives presidents “a unique opportunity for providing a quality of leadership that is sorely needed in our democracy,” he added.

But Franklin noted that certain conditions—such as alignment between the governing board and the president, and the trust of the community—must exist for presidents to be successful moral leaders. He believes the recent congressional antisemitism hearing “may mark a turning point in public trust and support for the moral leadership of university presidents,” calling the present moment a “toxic season of mistrust and conflict” that he hopes will soon pass.

Colleges could also do a better job of developing moral leaders for the future, he said.

“Schools of education and management should devote more attention to educating college presidents to be wise and capable of providing moral leadership on campus and beyond,” Franklin said. “Currently, we devote far more attention to training [in] effective management than to leadership that inspires and invites others to become better versions of themselves.”