You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Biden administration has been working out how to implement the CHIPS and Science Act since it was signed into law a year ago. But fully funding the legislation is up to Congress.

Saul Loeb/Contributor/AFP/Getty Images

When the CHIPS and Science Act was signed into law last August, colleges and universities saw an opportunity for the government to make a transformative investment in science and innovation. The ambitious legislation promised to bring tens of billions of dollars in new research money to American colleges and universities through federal science agencies, which fund more than half of their research and development.

“We really felt like it was an acknowledgment of what I would describe as the reinvigoration of the government-university-industry partnership, which has really driven our nation’s economy and our competitive position in the world on innovation for decades since World War II,” said Barbara Snyder, president of the Association of American Universities, which supported the legislation.

But one year later, Congress is already falling short of the ambitious funding targets called for in CHIPS. Snyder and others worry that lawmakers have focused on the investments in the semiconductor industry and forgotten about the “and science” part of the legislation, which authorized but did not fund tens of billions in new money for federal science agencies. It appears unlikely that the next federal budget will fully fund CHIPS, given Congress’s self-imposed fiscal constraints.

CHIPS authorized $200 billion in spending over 10 years for scientific research and development and commercialization, including $81 billion for the National Science Foundation, which would double the agency’s budget.

The act also outlined new investments in colleges and universities to develop the country’s workforce for science, technology, engineering and mathematics jobs. Some of the planned investments would also benefit historically Black colleges and universities, community colleges, and other types of institutions beyond the big research universities.

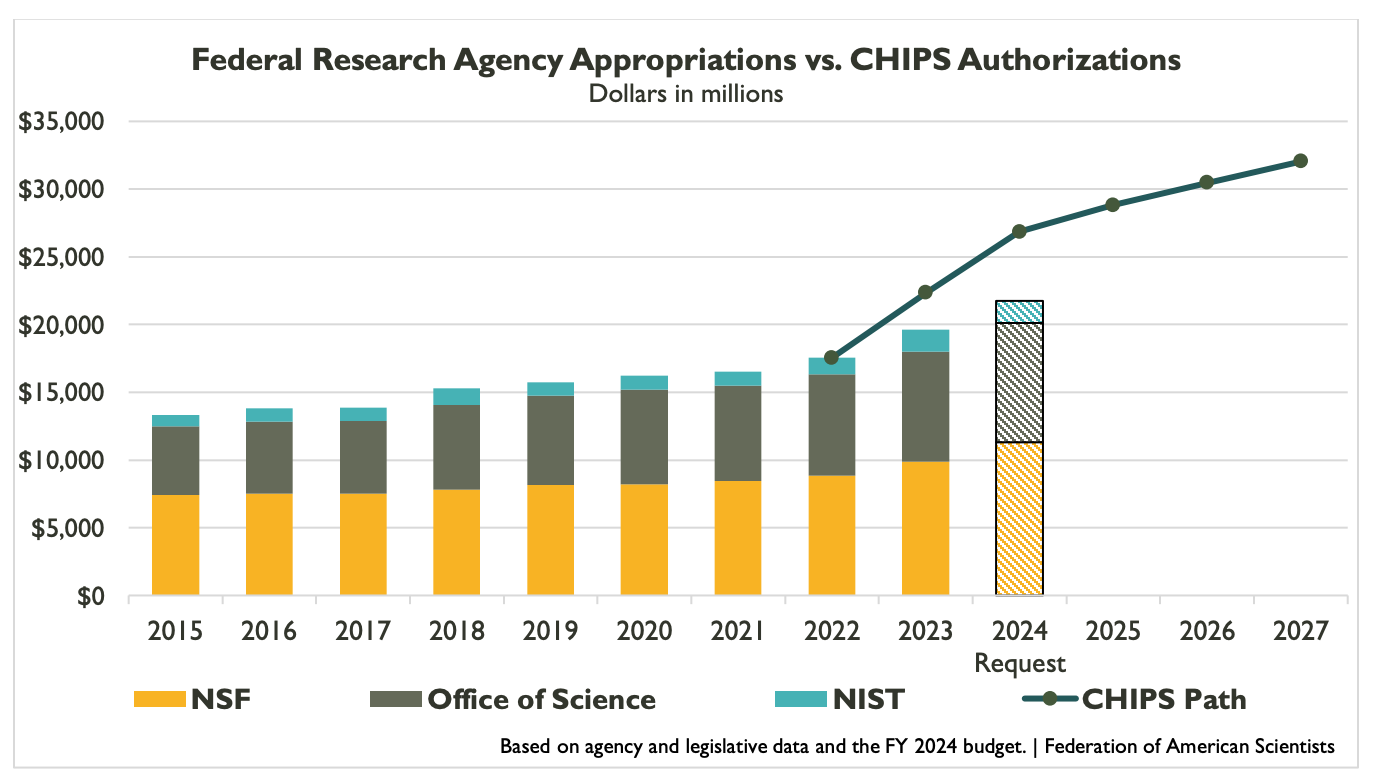

The first federal budget since the CHIPS and Science Act passed fell nearly $3 billion short of what the act called for. As Congress grapples with caps on funding and partisan divides over spending, meeting the CHIPS funding goals will be difficult.

Federation of American Scientists, May 2023

Touted as a key to maintaining a technological edge over China and other international competitors, CHIPS also put more than $50 billion into semiconductor research, development and manufacturing, some of which would flow to colleges and universities. That money was authorized and appropriated in the legislation, but the bigger potential boon for higher education institutions was expected to come from the science provisions of the bill.

Groups that backed the bipartisan legislation say that CHIPS won’t reach its full potential without full funding and are calling on Congress to stick with the legislation’s goals.

“Without funding, without support for things like graduate fellowships, that just means fewer opportunities for students, for young researchers, for postdocs,” said Matt Hourihan, an associate director at the Federation of American Scientists. “There’s a lot of tangible effects here in terms of lost opportunity. Once we start leaving these opportunities on the table, it’s hard. You can’t just go back and make up for them in the future. We seem to be digging ourselves a progressively greater hole.”

The House and Senate’s proposed science budgets would spend $7.7 billion less than what the legislation called for in fiscal year 2024. That’s on top of a roughly $3 billion shortfall in fiscal year 2023. The deal reached earlier this summer to avert a default on the federal government’s debt capped discretionary spending for the next two budgets, which will hamper efforts to meet the targets outlined in CHIPS.

Proposed 2024 budgets in the Senate and House keep funding relatively flat for the National Science Foundation, the Energy Department’s Office of Science and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the primary science agencies that were allocated new money in CHIPS. Funding from the NSF and the Energy Department made up about 15 percent of total federal support for university research and development in fiscal year 2021.

Under CHIPS, Congress was supposed to allocate $26.84 billion toward those agencies this year, but they would receive just $19.1 billion under the Senate’s plan and $19 billion under the House’s budget. The House Appropriations Committee hasn’t yet signed off on the science budget, though the Senate plan passed the committee in July with bipartisan support.

Fiscal 2023 funding for the government runs out Sept. 30. The fight over spending for fiscal year 2024 is expected to be contentious, with some House Republicans saying they’ll force a government shutdown to avert further spending increases.

Debbie Altenburg, associate vice president for research policy and government affairs at the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, said the proposed budgets do show that science funding is a priority, given that neither cuts the NSF’s previous budget significantly. Given the uncertainty around the budget process for this year, she said APLU and others will have to moderate expectations.

We’re in a critical moment here. The time really is now to get this done.

—Matt Hourihan, associate director, Federation of American Scientists

“We are likely in a situation where we are not going to see the growth path for NSF that we had hoped for with the passage of CHIPS and Science,” she said. “I think we are in a situation where we will have to work very hard to make sure that we protect the level of funding for NSF and NIST and some of these other programs in FY24.”

Progress on Chips, but What About Science?

Most of the $52 billion in the CHIPS portion of the legislation is aimed at revitalizing domestic semiconductor manufacturing. The U.S. makes about 10 percent of the world’s semiconductors, which are critical to modern electronic devices, while selling nearing half of them. The Biden administration began to roll out the CHIPS funding over the past year and carry out a number of projects outlined in the bill, such as establishing the National Semiconductor Technology Center.

CHIPS included $13.2 billion in research and development as well as workforce development, and colleges and universities are working to tap into that pot of money.

Dozens of community colleges have announced new or expanded programming related to the semiconductor industry, according to a White House news release. A coalition of university presidents and engineering school deans penned an open letter earlier this year outlining their plans to help build and diversify the semiconductor workforce. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo has said that colleges and universities need to triple the number of graduates in semiconductor-related fields, including engineering.

Altenburg said the advancements over the past year are exciting and worth reminding people about, but that the picture for fiscal year 2024 and science funding is concerning. Snyder agrees, noting that the investments in research and development are key to ensuring that the United States remains competitive globally. China and other countries have increased their investments over the past decade and could overtake the United States in funding research and development.

“We think it’s critical that Congress gets the message to fund American science to keep our economy robust, keep our national security strong and keep our nation healthy,” Snyder said. “We just think that the investment that was called for CHIPS and Science is essential even in times when budgets are tight. In some ways, that’s the time when it’s the most important, because the results that they produce multiply many times and really can make an enormous difference.”

Snyder wants Congress to adhere to the original targets in the CHIPS Act, though she acknowledged that some investment is better than none.

“It was the right thing then because, again, it’s a long-term play, and it’s still the right thing if we’re going to be competitive,” she said. “I think the American people want and expect us to be the world leader in innovation. I think they want us to lead the world in science, and I think we want to keep doing that. But that does not come without investment.”

Hourihan said the CHIPS Act was intended to address a variety of priorities, from STEM education to research infrastructure to support for emerging technology such as artificial intelligence. A lack of funding will mean thousands of fewer research awards and delays in projects to update facilities, among other consequences.

However, the act itself is bigger than one or two budget cycles, and Hourihan and others aren’t calling time of death for the science investments yet.

“Even if Congress drops the ball on investing in CHIPS and Science now, I can only expect there will continue to be a need down the road to invest,” he said. “But we’re in a critical moment here. The time really is now to get this done.”