You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The most recent proposal is the final piece of the Biden administration’s second attempt to provide debt relief to millions of Americans.

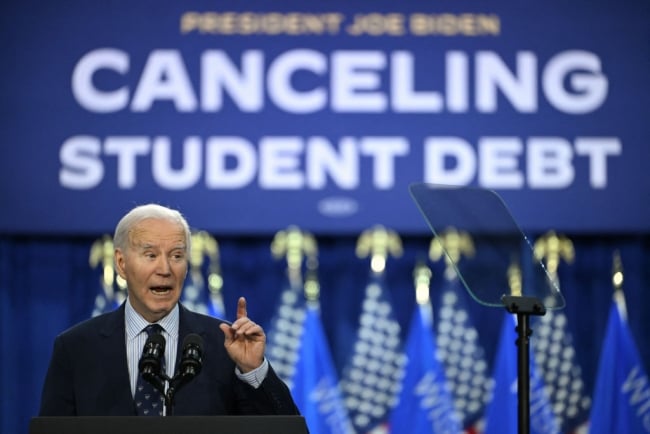

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images

President Joe Biden’s latest debt-relief plan would benefit eight million people, if enacted, but the plan will likely face legal challenges and might never see the light of day.

The long-awaited proposal, released Friday and geared toward helping borrowers experiencing financial hardship, is the final piece of the Biden administration’s second attempt to provide student debt relief to millions of Americans. The first effort, which would have benefited 43 million borrowers, was struck down by the Supreme Court in June 2023, prompting the president to go back to the drawing board.

The newest plan builds on the administration’s proposal released earlier this year that provides a pathway to relief for borrowers who owe more they initially borrowed or who have spent more than 20 years paying back their loans, among other groups. Under that plan, which is not yet final and on hold in the courts, the department would forgive all or some of nearly 28 million Americans’ student loans.

But debt-relief advocates have repeatedly argued that the plan was incomplete without a catchall measure to help borrowers who are experiencing financial hardship. Department officials said the plan is crucial, as no one should worry so much about student debt that they forgo pursuing a college degree entirely.

“The whole point of taking out a student loan in the first place is to invest in the future, to invest in skills and education in order to expand opportunity and to get ahead, not to fall into a debt trap when hardship strikes,” national economic adviser Lael Brainard said in a press call Thursday. “When hardship strikes, student debt relief is unequivocally good for borrowers [and] good for economic opportunity.”

As with previous iterations of debt-relief plans, criticism of the proposal was swift and forceful, with conservative advocacy groups and congressional Republicans decrying it as nothing more than a third attempt to shift repayment responsibility. Supporters of the proposal applauded the Biden administration for providing new routes for forgiveness and standing up to Republicans.

The department is planning to publish the proposed regulations in the Federal Register “in the upcoming weeks,” according to a department release, and will then take public comments for the 30 days. After that, department staff must review and respond to every comment before issuing a final rule.

Officials didn’t say last week when they hope to release the final rule, but the clock is ticking. The department has until late January to finish its work before a new administration takes over following next week’s election. Any rules issued in the final days of the Biden administration could be rolled back by former president Trump, if he wins, or Republicans if they control Congress, depending on when the regulations take effect.

“This president has been clear that within the scope of the department’s legal authority, his directive to his administration is to deliver as much as possible to as many people as quickly as possible,” a senior administration official said when asked about a finalization date.

How the Plan Works

The hardship proposal would grant the department the ability to waive up to the entire outstanding balance of a student loan when a borrower experiences an unanticipated expense—such as medical bills, high childcare costs, caring for loved ones with chronic illnesses, or natural disaster—that could impair their ability to fully repay the loan.

“Just over the past month, we’ve seen the devastation people can face when disasters like Hurricane Helene and Milton strike,” Brainard said. “Families are losing their homes, their belongings are ruined, small businesses are shuttering, there are thousands with new medical bills. The repayment of student debt just shouldn’t be an additional burden.”

Borrowers would be able to access relief under two pathways, as outlined in the draft regulations.

The first would allow the department to grant one-time automatic relief to borrowers who have an 80 percent chance of defaulting on their loans in the next two years. The department would take into account 17 factors to make that determination, which include a borrower’s outstanding balance as well as whether they completed college or receive means-tested public benefits, among others. Borrowers who qualify could see all of their loans wiped out, or the department could opt to only discharge some of the outstanding balance.

Two-thirds of borrowers eligible for relief under the first pathway received the Pell Grant, according to the release.

The second pathway is less formulaic and requires borrowers to apply for relief. Under this path, the department will conduct a holistic assessment to determine whether a borrower is likely to default or “experience similarly severe negative and persistent circumstances,” according to the release.

“If no other payment relief option exists to sufficiently address the borrower’s persistent hardship, the secretary could waive the loan,” officials wrote.

With both pathways combined, the latest relief plan is estimated to cost taxpayers $112 billion over 10 years, according to the proposed regulations. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget has estimated the plan will cost about $600 billion. Department officials argued that there is money to be saved if the agency stops trying to collect loans that are unlikely to be repaid in full.

“A big reason why we’re fighting for student debt relief is to address the more than one million defaults we see annually in the student loan system,” Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona said on the press call Thursday. “Remember, servicing and collection of defaulted loans is not free. It costs taxpayers and can harm borrowers. And there’s a point when the cost of trying to collect on a defaulted loan just is not worth it.”

Divided Reactions

Kyra Taylor, a staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center who was part of the negotiating committee, echoed Cardona’s comment in a statement, saying that the current student loan system is broken and debt relief will allow the federal government to be better stewards moving forward.

“The student loan system is bloated with debts that will never be repaid, and the ongoing efforts to collect these bad debts endanger the Department of Education’s ability to adequately service the rest of the student loan portfolio,” she said. “This proposal creates a pathway to ensure that student loan borrowers won’t languish under the weight of their student loan debt going forward.”

Other supporters including the Student Debt Crisis Center and Young Invincibles, an advocacy group focused on amplifying the voices of young adults, said higher education should be a bridge to equitable opportunity and cost should not be a barrier before or after graduation.

“The new rules recognize that student debt isn’t just about past borrowers—it’s about protecting future generations, too,” Kristin McGuire, executive director of Young Invincibles, said in a statement.

But others, including conservative think tanks and congressional Republicans, argue the restrictions on what constitutes a hardship are vague and the latest plan simply shifts repayment responsibilities.

“Where is the forgiveness for the guy who didn’t go to college but is working to pay off the loan on the truck he takes to work? What about the woman who paid off her student loans, but is now struggling to afford her mortgage?” asked Dr. Bill Cassidy, a Louisiana Republican and ranking member of the Senate education committee. “Is the administration providing them relief? Of course not.”

The Cato Institute Center for Educational Freedom, part of a libertarian think tank, noted that past debt relief plans have run into “enormous” constitutional and legal challenges, and this plan is likely to as well.

“The most notable feature of this plan involves the Department of Education proactively forgiving debt for borrowers that it predicts will default on their student loans. But that just raises the question, if the Department can predict which loans will default, why are they making those loans in the first place?” said Neal McCluskey and Andrew Gillen, center director and fellow, respectively. “In any other context, making loans that have a high probability of never being repaid is called predatory lending.”