You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

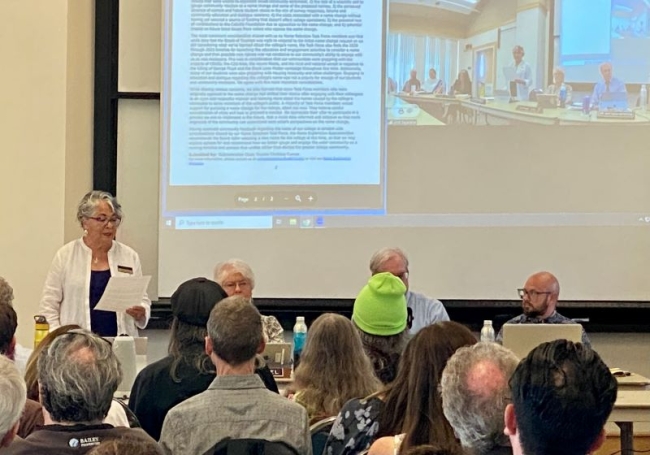

Christina Cuevas, Governing Board member and chair of the Name Exploration Subcommittee, speaks to the board and attendees at a meeting earlier this month.

Cabrillo College

The Cabrillo College Governing Board recently voted to delay a long-awaited name change for the campus after a more than two-hour public discussion. The heated board meeting earlier this month is the latest episode in a series of informational events and public forums held by the college regarding the name change. Board members voted 6-1 to pause the name selection expected to take place that day.

Proponents of an immediate name change say the move is long overdue given the history of the college’s namesake, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, a 16th-century Spanish explorer known for his violence toward Native Americans. Opponents say the branding change is costly and unnecessary and risks alienating donors, alumni and locals. College leaders and board members who favor postponing the process hope an extended timeline and more discussions between proponents and opponents will alleviate concerns.

Matthew Wetstein, president of the college, said the community needs more time to weigh in on the process and that the college needs to do more work to educate the community about the decision.

“The college needs time to be able to make the case better if we’re going to make a name change, and that kind of understanding has to be developed over time. We’re at this pause in time to say, ‘Okay, how do we get to a point and maybe develop a plan that allows for some of that to happen.’”

Steve Trujillo, the board member who voted in favor of an immediate name selection, believes the college has waited long enough. He noted that Cabrillo was founded in 1959 “so this conversation that we’re having is 65 years overdue.”

College employees and students called on campus leaders to replace the name in a 2020 petition during the national racial reckoning that followed the police killing of George Floyd. That summer, the board established a Name Exploration Subcommittee of three board members and an advisory task force made up of student, college foundation, faculty and staff representatives to consider a process for renaming the college and involving various stakeholders on campus. The subcommittee recommended in a report last November that the college go through with the name change, and the board voted in favor of starting that process.

A name selection task force then settled on five names to consider, winnowed down from about 350 suggestions, and the college held a series of community forums this summer to discuss them. Aptos College proved to be the most popular choice in surveys. The name, which refers to the town in which the campus is located, is also the name of a Native American tribe and an Oholone word for “the people.”

The subcommittee ultimately recommended delaying choosing a new name. Christina Cuevas, a board member and chair of the subcommittee, cited a number of reasons for doing so, including concerns among task force members about “strong opposition” to the name change process and the name suggestions. She said task force members also worried about the lack of a “scientific poll to gauge the community’s reaction,” “limited representation of current and future student voices” in surveys and forums, insufficient funding to cover costs associated with the name change, and fears that upset donors might pull back their gifts.

Cuevas told Inside Higher Ed that when she met with task force members in July, including some initial name change opponents, most agreed “the decision to change the name was the right decision, albeit not right now.”

The board vote this month postpones a final decision until at least November. The subcommittee will update the board on plans for next steps and outreach with name change opponents. There’s no set timeline for finalizing a name, subcommittee members said.

Prior to the vote, public comment stretched on for more than two hours. Speakers, including local residents, employees and students, passionately advocated for and against the name change.

Dana Frank, a research professor and professor emerita of history at the University of California Santa Cruz, spoke out in support of the change.

“The core question is what do we want to teach?” she said. “In keeping the name, we would be teaching day in and day out that it’s good to celebrate those who invaded other people’s ancestral homelands, killed and in many cases enslaved them.”

Paul Meltzer, an alumni and former member of the college’s foundation board, said the cost of changing Cabrillo’s name and branding has been estimated at up to $600,000. He believes that’s too steep a price for a symbolic gesture and would be better spent on student scholarships or accessibility improvements for disabled people.

“I love Cabrillo College, and I don’t love Juan Cabrillo,” he said. “But of the 99 problems facing Cabrillo College, a name change doesn’t even make the list …” he said. “Much has been said here about a name change without any discussion of the cost.” Cabrillo’s legacy is “irrelevant and doesn’t matter.”

A National Conversation

Higher ed institutions across the country have undertaken similar efforts to rename academic buildings and campuses in recent years in response to demands by students and employees to remove statues of racist figures, and take their names off campus buildings. Princeton University removed the name of former president Woodrow Wilson from its public policy school in 2020 because of his support for segregationist policies. The University of California Berkeley renamed its law school that same year, which had previously been named after John Henry Boalt, who advocated for the banning of Chinese immigrants from the United States in the late-19th century. The Virginia State Board of Community Colleges pressed several colleges to change their names because their original namesakes were public figures who owned slaves or promoted racist policies. The moves sparked controversy among alumni and other stakeholders, much like at Cabrillo.

“Certainly, the Black Lives Matter movement brought to the fore a lot of issues people have been asking to have changed or addressed for a long time, but that just hadn’t received that national level of attention,” said Heather O’Connell, associate professor of sociology at Louisiana State University.

She said resistance to name changes is often about nostalgia, fear of change and “control over public spaces.”

“… That symbolic control is valued,” she said. “It’s a commodity. The naming of buildings, places, campuses are part of that value. And so changing that is sort of a changing who has control over that space.”

Adam Spickler, chair of the Governing Board and a member of the subcommittee, noted that despite being under consideration for three years, the public reaction to the name change became more vocal as the pandemic and area wildfires waned.

He said the subcommittee also wants time to engage newly enrolled students in conversations about the name change, which has divided alumni and current students and employees and further complicated the debate.

Alumni feel a “nostalgia” for the “brand name,” while people currently working or studying on campus are “much more likely to say, ‘Yeah, but the brand is damaged by having the name association,’” he said.

Trujillo, the board member who voted for the immediate name selection, said he understands that nostalgia but Cabrillo’s name has got to go.

“People are automatically attached to the name because they had wonderful years at our school either as an employee or student or both, and I get that,” he said. He recognizes that “cognitive dissonance” but “our motto is diversity, equity and inclusion … He's the opposite of everything we profess to believe.”

Trujillo researched Cabrillo when he was a high school teacher developing a Mexican American history class and was “shocked” by stories about his treatment of indigenous people.

“It’s very disconcerting to find out this man was a bastard,” he said. “He was a terrible, evil man, and we should thank God he never stepped foot in our county.”

Trujillo said he’s been reaching out to potential donors in hopes of securing the funds needed to replace signage and to pay for other expenses related to the name change. While he’s against the recent delay, he praised the subcommittee for its commitment to robust, public discourse on the issue.

Wetstein said many of the previous public forums about the name change were held on Zoom and community members have expressed strong opinions on social media or in emails to college officials.

He hopes that the pause allows for more in-person dialogue.

“You get so much more benefit if you do it in person and have to sit and listen and interact with each other in a room together,” he said. “We need more of that, not less.”

O’Connell said opponents of name changes sometimes argue names are insignificant but there’s a reason they stoke so much debate.

“From my perspective, our names and our public symbols, they’re not nothing,” she said. “Otherwise we wouldn’t care about them. The fact that people are so concerned about what the name is and whether something gets changed says to me that this is worth fighting for, this is worth having a conversation about,” she said. “Because it … shapes how we think about and interact with these spaces.”