You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

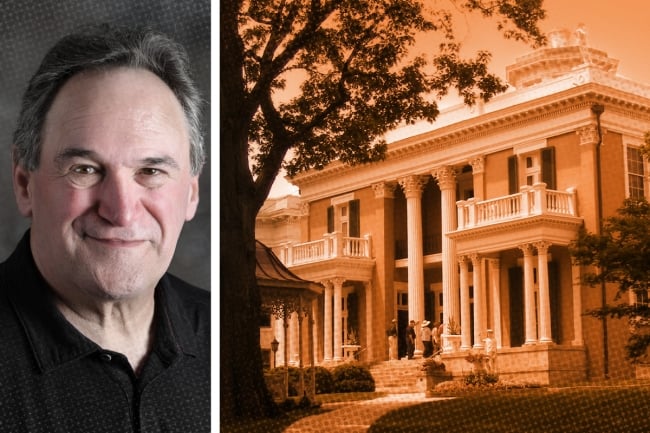

Rabbi Mark Schiftan will be Belmont University’s first Jewish student faith adviser.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Belmont University | EVula/Wikimedia Commons

Belmont University in Tennessee, which proudly describes itself as a “Christ-centered” institution, has diligently been building bridges with Nashville’s small Jewish community. In a further attempt to strengthen those ties, the university just hired a rabbi.

“We’ve had a longtime relationship with Rabbi Schiftan through our Jewish-Christian initiatives,” Greg Jones, president of Belmont, said of the new campus rabbi, Mark Schiftan. “This seemed like a really good development for our Jewish students and for the larger context of our relations with the Jewish community in Nashville.”

Schiftan, rabbi emeritus at a local Reform synagogue, was tapped for the inaugural role of the Nashville institution’s Jewish student faith adviser, according to an announcement earlier this month. He’s responsible for holding office hours and twice-monthly meetings with the university’s small Jewish student population and helping to run monthly Shabbat gatherings, holiday prayer services and other learning and social events with Belmont’s Jewish student organization.

“My goals are, first and foremost, that the Jewish students have a place that they can turn to, a person that they can turn to, that can hear their struggles and their questioning about their own faith and about being part of a wider Christian university,” Schiftan said.

Jewish students only make up 1 percent of the nearly 9,000 students at Belmont. (More than half are Protestant, 15 percent are Catholic, 1 percent are Muslim and 8 percent identify as having no faith at all.) But the university has been pouring resources into Jewish-Christian relations and making policy changes to accommodate its still sparse but growing community of Jewish students.

Notably, the university announced plans last year to break with a long-standing tradition of hiring only Christian faculty members and opened up positions in its law school, pharmacy school and new medical school to Jewish applicants. Meanwhile, Jon Roebuck, who directs Belmont’s Reverend Charlie Curb Center for Faith Leadership, and Schiftan have been co-leading a weekly online interfaith dialogue group for Christian and Jewish clergy and lay leaders for almost four years. The university also launched the Belmont Initiative for Jewish Engagement in 2021, a slew of programming and events focused on the two groups. Jewish students at Belmont held their first services for the High Holy Days last fall.

“They’re our closest siblings religiously,” said Jones. “Christians can learn better how to live as Christians by deepening understanding of how Jews live as Jews.” He added that it’s “urgently important” for Christians to “resist antisemitism” after a “sad history” of having done otherwise in the centuries leading up to the Holocaust.

Schiftan believes his role, and the university’s new openness to Jewish faculty members, could be an “enormous draw” to Jewish prospective students. Data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation showed high numbers of antisemitic hate crimes in the U.S. in the decade before the Israel-Hamas war, but the turmoil has spurred a further “rise in threats to Jewish students” at campuses across the country, including at “so-called elite universities,” he said. (Muslim and Arab students have also reported hateful incidents.)

“A Christian university, ironically, might be the place where a Jewish student feels the most welcome,” he said. “In light of the events in Israel after Oct. 7 and this dramatic rise of antisemitic sentiments and threats on these major college campuses, I definitely think that there will be many more Jewish parents who feel that they want their children to go to a place that is actually very protective of … who their children are and very sensitive to the needs of those students.”

Schiftan said Belmont recently gave students of all faiths excused absences for non-Christian religious holidays and introduced High Holy Day and monthly Shabbat services and social gatherings for Jewish students. None of these supports existed a few years ago.

“It might not sound like many [programs], but we’ve come a long way,” he said.

Jones said there are no plans to hire chaplains or advisers for other minority faith groups at this time, though “we’re looking for ways to provide services for them as well.”

An Outlier or a Trend?

Belmont isn’t the only Christian university that sees itself as a potential destination for Jewish students.

Franciscan University of Steubenville in Ohio, a Catholic institution, began offering an expedited transfer process to Jewish students in October in response to rising tensions on campuses over the Israel-Hamas war. Walsh University, also a Catholic university in Ohio, made the same offer.

Greg Weiner, the Jewish president of Assumption University, a Catholic institution in Massachusetts, argued in The Wall Street Journal that Jews should consider Catholic universities because “they avoid the heat of contemporary events and instead fix their attention on enduring questions.”

The interest in Christian-Jewish engagement also seems to go both ways. Yeshiva University, a Modern Orthodox Jewish institution in New York City, launched a new program aimed at Christian students last fall in which they earn a master’s degree in Jewish studies from the university and a certificate in Hebraic studies from the Philos Project, an organization that advocates for Christians in the Middle East and encourages Christians to connect with their “Hebraic tradition.”

More broadly, some Christian institutions have adjusted their policies to open their doors to a wider range of students. For example, Multnomah University, a nondenominational Christian institution in Oregon, last fall dropped its requirement that all incoming students sign a faith statement.

Amanda Staggenborg, chief communications officer at the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU), said in an email that the organization’s member institutions “are good places for all students serious about faith and frequently enroll Muslim students” as well as international students who “may bring non-Christian faith traditions.” (Belmont is not a CCCU member institution.)

“Respect for faith differences is very present with the hope that the compelling story of the Christian faith is attractive to all students,” she said.

Yet, in spite of these efforts, few Christian institutions have made sizable investments in Jewish student life, said Jonathan S. Coley, associate professor of sociology at Oklahoma State University.

Coley, who’s conducted research on students from minority faiths, noted that only a quarter of colleges and universities nationwide have Jewish student groups, according to 2020 data. Meanwhile, secular higher ed institutions were “much more likely” than their religious counterparts to have these groups, 34 percent and 12 percent, respectively.

Belmont’s supports for Jewish students are even more of a rarity among Christian universities of its kind. The institution was formerly affiliated with the Southern Baptists, a prominent evangelical Protestant group, but it became nondenominational after it broke ties with the Tennessee Baptist Convention in 2007. (The relationship ended because the university wanted to be able to choose its own trustees.)

Coley found that “nearly all” of the religiously affiliated colleges and universities with Jewish student groups were Catholic or mainline Protestant, institutions that “by and large have no expectation” that students or employees have to be Christian. (Some Catholic institutions were also founded amid Jewish and Catholic immigration waves and enrolled Jewish students at times when other universities had quotas limiting the number of them admitted.)

In contrast, Coley found “very, very few” nondenominational Christian colleges or evangelical colleges with these student clubs. He noted that evangelical institutions in particular “historically expected their faculty and staff to be Christian and largely expect their students will be Christian” or at least uphold “Christian moral standards” while on campus.

“Belmont University is quite unusual in having … really any kind of support as far as I can tell for Jewish student groups,” let alone a dedicated adviser for them, Coley said.

But he wouldn’t be surprised if more Christian colleges followed suit in future years, as many higher ed institutions face enrollment declines and an impending demographic cliff.

Belmont’s enrollment has largely held steady: total student head count only dropped 0.4 percent between 2022 and 2023, from 8,910 students to 8,872, according to university data. Otherwise, enrollment has been increasing over the last decade, aside from a dip in 2020.

But not all Christian universities have fared as well. Data from CCCU show average enrollment began dropping for higher ed institutions over all in 2011 and for CCCU member colleges in 2015. Enrollment at CCCU institutions fell by almost 9 percent from 2015 to 2021.

Higher ed will “be facing even steeper declines in enrollments in the coming years as the college-age student population drops,” Coley said. “I think more and more Christian colleges and universities in the United States will face pressures to become more open to a wider variety of students.”

Eboo Patel, founder and president of Interfaith America, an organization focused on fostering interfaith ties, said there is a “pragmatism” to Christian colleges engaging in interfaith work in “the most religiously diverse nation in human history,” especially as Muslim and Hindu populations grow in the U.S. But he more so believes that leaders of these institutions genuinely view interfaith work as a part of their own religious values, and he sees them doing more of it in recent years.

Patel has been invited to speak about religious pluralism at CCCU conferences and about a dozen Christian college campuses. And his organization also developed an interfaith engagement curriculum for Christian college students in partnership with some of these institutions, among other programming.

He noted that some institutions, like Belmont, have started their interfaith work with a focus on Jewish students, in part because historically large percentages of American Jews attend college. But he believes similar initiatives with other minority faith groups will follow.

“I think it will happen soon,” he said. “Once you take a step along faith as a bridge, you soon find that you meet all different kinds of people that you like and that you want to spend time with and want to learn with.”