You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A computer science lecture at Harvard University, part of the program that topped the College Scorecard in median earnings. STEM graduates earned far more than others on average.

Maxim Aleksa/CS50 at Harvard University

New data from the Department of Education’s College Scorecard show that tech and STEM majors still vastly outpace liberal arts and humanities majors in terms of future earnings.

The data, released April 27, compare the relative earnings of graduates of more than 36,000 different programs across institutional sectors, from community colleges to for-profit institutions. Computer science programs made up 16 of the top 20 slots on the list, and all but five of the top 100 programs were in STEM fields; the others were in finance or economics, with the exception of Carnegie Mellon University’s Design and Applied Arts program, which came in at 96.

Computer science programs at elite universities like Harvard University and the California Institute of Technology earned the top five spots for four-year degrees, with graduates earning average salaries of over $240,000 four years after receiving their diplomas. The five lowest-earning bachelor’s programs included health-care programs at universities in the Caribbean and Puerto Rico, a music degree from Brigham Young University, and the Fine and Studio Arts program at the California Institute of the Arts, whose graduates make a median of $13,336 a year.

Many associate degrees in STEM fields such as nuclear engineering—as well as credentials in high-paying vocations like nursing—led to significantly higher median earnings for graduates than over half of the four-year degrees included in the study. The median income for those who earned an associate degree in nuclear engineering from Bismarck State College, for instance, was $140,386—almost three times as high as the median salary for a journalism major from the University of Arkansas.

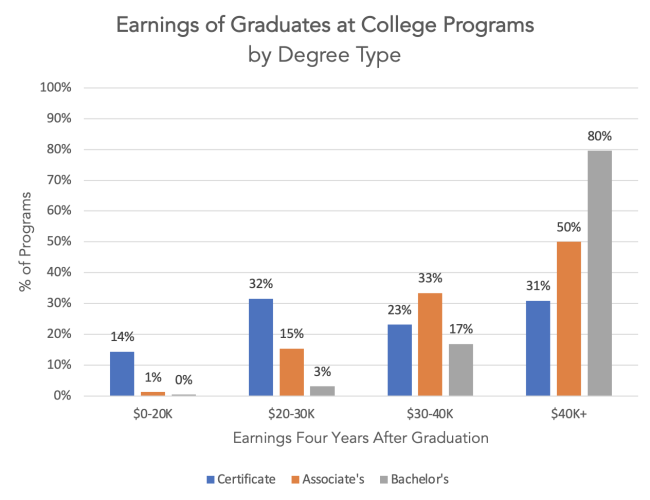

A graph comparing median earnings of certificate, associates and bachelors degree earners across degree fields. The Scorecard data showed many two-year or certificate programs in STEM fields led to higher earnings than four-year humanities degrees.

Michael Itzkowitz/HEA

Michael Itzkowitz, founder and president of the higher education consulting group HEA, has pored over each batch of Scorecard data for years and said he wasn’t surprised by the results.

“Earnings from STEM degrees have been historically and consistently much higher,” he said. “That’s just kind of always been the case.”

The new data come at a time when Americans are increasingly doubtful that a college degree is worth the average price of admission, and as institutions and policy makers look to trim fat and prioritize high-return programs in the face of looming enrollment declines and rising costs. The future viability of humanities programs is also raising alarm.

The Education Department pulls the data from IRS filings and uses federal financial aid records to tie graduates back to their institutions and degree programs, which means it only accounts for program graduates currently in the workforce who qualified for federal aid.

This is the fourth year that the department has collected data on specific degree programs, and thus the first time outcomes can be viewed four years after graduation. Itzkowitz said that makes them the most accurate and telling data to date on programs’ economic returns.

But not everyone is sold on the data’s importance. Patricia McGuire, the president of Trinity Washington University, said she doesn’t think tying earnings to specific degree programs is as relevant to employers or students as some researchers and policy makers suggest.

“It is certainly true that many vocations or industrial jobs require specific skill sets, and that’s what’s going to get those students the best careers,” she said. “But most corporate employers want graduates who can read and write and think. You can train someone to build software after you hire them. It’s much harder to give someone critical thinking skills and a wide base of knowledge, and that’s where liberal arts comes in.”

Practical Applications

Itzkowitz’s HEA released an analysis of the Scorecard data Tuesday, along with a spreadsheet organizing them into different categories. His main takeaways are that often the program a student chooses can matter more than the institution, and that institutions struggling to recruit students should focus on programs that differentiate them and lead to the highest return on investment.

“It provides a flag to areas where those presidents can at least begin to dig deeper to understand what’s not working in specific programs,” he said. “And there’s a role for federal and state policy makers here to play as well in terms of the most effective use of taxpayer dollars per student.”

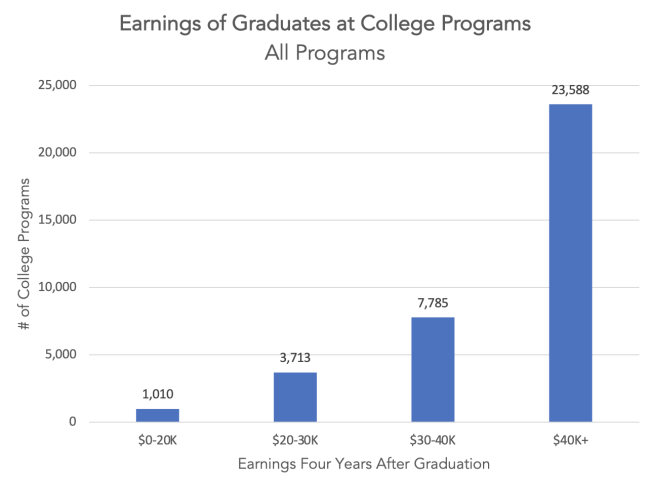

A visualization of the College Scorecard data showing that the majority of higher ed programs produced graduates earning $40K a year or more. Those earning above $80K tended to have STEM degrees.

Michael Itzkowitz/HEA

Martin van der Werf, director of editorial and educational policy at Georgetown University’s Center for Education and the Workforce, said data like the Scorecard’s are “going to be increasingly important” in this regard.

“Data on earnings is just one metric, but for a lot of students it’s a really important one,” he said. “So from both an institutional and public policy standpoint, these are going to be increasingly important data points to address increasingly important questions.”

McGuire said what makes research like the Scorecard data so dangerous is the way they are wielded. Emphasizing economic returns, she said, is part of a destructive agenda driven by those who want to defund and marginalize higher education in American society.

“Part of the problem is that this research and reporting in the public sphere ends up becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy,” McGuire said. “This obsession with exactly what kind of job you have and how exactly that’s tied to your major is really new, and it’s very political. It is absolutely driven by a political system that is attacking higher ed all over.”

‘Stripping Away Passion’

The Scorecard’s focus on financial returns has its detractors in higher ed, who say it ignores students’ many noneconomic reasons for pursuing a particular field of study.

McGuire said Trinity, a historically women’s college in D.C., collects its own alumnae data on employment and degree returns but focuses on factors besides ROI, such as personal fulfillment and community service.

“There are reasons students pick certain careers that have nothing to do with earnings. It’s about service and passion,” she said. “This whole discussion around earnings strips that idea of passion out of the equation and reduces the decision-making matrix to dollars and cents, which I think is frankly unethical.”

McGuire also said focusing on earnings can obscure realistic outcomes for groups vulnerable to pay disparities, like Black graduates and women. She added that Trinity’s student body, which is 95 percent students of color—65 percent of them Black—and nearly all female-identifying, is particularly misrepresented by the Scorecard data.

“Earnings data is inherently skewed against graduates who are Black, Hispanic or women,” she said. “To understand the data as it relates to a student body, an observer would have to go probing and actually know about wage discrimination, race and gender discrimination and so forth, and factor that into the calculations.”

Van der Werf said that while earnings alone are “probably not the first thing students think about” when deciding where to apply to college, it can be particularly helpful for those comparing several similar programs at different institutions, and it is clearly an “increasingly important metric” for leaders making tough decisions regarding institutional finance or lawmakers allocating public funds.

“Colleges have mushroomed in recent years, just grown so much, and many aren’t differentiating themselves,” he said. “So what I think we’ll see, especially at public systems with multiple campuses, is programs being consolidated, offered at one or two institutions instead of all of them.”

At the same time, van der Werf added, good gainful employment for students and productive workforce development outcomes for regional and state economies are often completely unrelated—or even at odds.

“We can’t all be engineers. The world needs more social workers, more teachers, and those tend to be degrees with a lot less return on investment,” he said. “So you wouldn’t want lawmakers or institutional leaders to only use the earnings data to make decisions about program cuts, for instance. It’s just one factor.”

“But,” he added, “it is becoming a more and more important factor.”