Free Download

Employee engagement: it’s an important metric that can gauge how loyal and intrinsically interested people are in their work. So how engaged are faculty members, and how do they compare to other kinds of workers? A new Inside Higher Ed survey, conducted by Gallup, suggests that while faculty members over all aren’t actively engaged in their work, those at smaller, private institutions tend to be the most emotionally and intellectually connected to what they do. Tenure-track faculty members are also relatively engaged, possibly from the coaching and mentoring they receive, as compared to tenured and non-tenure-track professors. The survey also reveals that many faculty members -- especially those off the tenure track -- have major concerns about academic freedom, job security, compensation and other measures of job satisfaction.

Loving What They Do? Not So Much …

Some 34 percent of faculty members surveyed are engaged in their jobs, meaning that they are more involved in and enthusiastic about their work, and -- as a result -- more loyal and productive, according to the 2015 Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Faculty Workplace Engagement. Some 52 percent of faculty members were not engaged, according to Gallup’s metrics -- 12 questions that assess workers’ sense of belonging and purpose and degree of mentorship, among other things. Statements with which respondents agree or disagree include:

More About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2015 Survey of College and University Faculty Workplace Engagement was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

On Thursday, Nov. 19, Inside Higher Ed's Scott Jaschik and Doug Lederman conducted a webinar analyzing the survey's findings and answering readers' questions. To view the webinar, please click here.

The survey was made possible in part by financial support from TIAA-CREF.

- At work, my opinions seem to count.

- There is someone at work who encourages my development.

- In the last six months, someone at work has talked to me about my progress.

- The mission or purpose of my institution makes me feel my job is important.

- At work, I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day.

Not engaged isn’t as bad as it sounds, since those who aren’t engaged still may be productive and satisfied with their jobs. But they’re not intellectually or emotionally connected to their workplace, according to the Gallup metric. Actively disengaged faculty members -- some 14 percent -- are physically present at work but emotionally disconnected.

Brandon Busteed, executive director of education and workforce development at Gallup, said engagement matters because studies show that engaged employees are more productive, less likely to be absent or have sick days and have lower health care costs. And in business, he said, they drive more revenue and profit. Not engaged doesn’t mean someone isn’t a good worker, he said, but he or she “may be doing their basic job functions and performing based on minimum expectations, but they do not necessarily bring new ideas and energy to their work.”

And those who are actively disengaged? They’re not “just miserable,” he said. Rather, they’re “vocal about that misery and work to spread it to others.” It’s a quality that might be particularly destructive in higher education, where faculty members who land tenured positions tend to stay in the same place -- on the same teams -- for a long time.

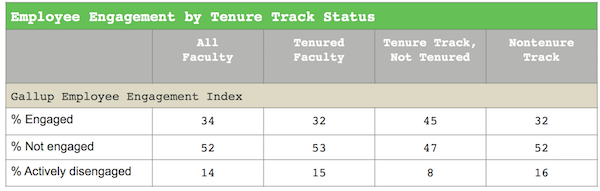

Consistent with Gallup’s expectations, full-time faculty members were more likely to be engaged in their work than part-time faculty members, at 34 percent and 30 percent engaged respectively. Also unsurprisingly, respondents’ tenure status corresponded with their levels of engagement. But the details are interesting: while 45 percent of tenure-track faculty members are engaged, there’s no significant difference in engagement levels among tenured and non-tenure-track faculty members. About 32 percent of both latter groups are engaged.

Besides the obvious fact that tenure-track professors are working against a high-stakes deadline -- their tenure review -- a few factors separate tenure-track faculty members from their peers, according to the survey. That’s having someone at work who encourages their development and having had a conversation about their progress within the last six months. Slightly more than half of tenure-track instructors strongly agree with those statements, compared to much lower proportion of their colleagues. Over all, just four in 10 professors strongly agree they’ve been talked to about their progress in the last six months, for example.

Tenure-track faculty members are also much more likely than their peers to strongly agree that someone at work cares about them as a person and that they have opportunities at work to learn and grow.

The data indicate that faculty members and administrators may not see that kind of checking in or mentoring necessary for professors who already have earned tenure or for those not eligible for tenure, according to the survey prepared by Gallup. “Given those differences, it may be the case that once professors are tenured, their employee engagement is at serious risk of falling if their colleagues no longer view development of their jobs and career as an area needing attention,” it says.

Busteed said this was the most telling set of questions in the entire survey.

“Tenure-track faculty are twice as likely to strongly agree they have someone who encourages their development and that someone has talked to them about their progress, compared to tenured and non-tenure track,” he said. “From these data it appears that higher ed’s ‘stars’ -- tenured faculty -- aren’t being supported and encouraged relative to when they were on the tenure path, and that seems like an opportunity for improvement.”

Busteed cautioned, however, that more qualitative study is needed to determine tenured faculty members’ needs and desires in terms of support, since they may be different from those of tenure-track faculty members.

Engagement by Institution Type

Faculty members working at private institutions are more likely to be engaged than their public institution peers, at 36 percent and 31 percent engaged, respectively. Professors at private baccalaureate institutions drove up the private figure, since they were the most engaged group: 39 percent over all. They were especially more likely than their peers to say they know what’s expected of them at work, that their opinions count and that they have opportunities to learn and grow.

Engagement levels are about the same -- roughly 30 percent -- among faculty members teaching at private or public doctoral- or master’s degree-granting institutions, public baccalaureate institutions and public associate degree-granting colleges.

Engagement seems to correlate with lower enrollment numbers. Thirty-seven percent of faculty members teaching at institutions with fewer than 5,000 students are engaged, versus 32 percent engaged at institutions with 5,000 to 10,000 students. The faculty engagement rate was 29 percent for those teaching at institutions with an enrollment of 10,000 or greater.

The Gallup report speculates that could be because faculty members at small institutions have a greater opportunity for student interaction with smaller class sizes, and might be able to focus more on teaching than faculty members at larger, research-oriented universities. Professors at small institutions may also feel that they have a greater say in university affairs.

Faculty members teaching in professional schools tend to have higher engagement rates than their peers, at 36 percent. That’s compared to 33 percent in the natural sciences, 32 percent in the social sciences and 31 percent in the humanities.

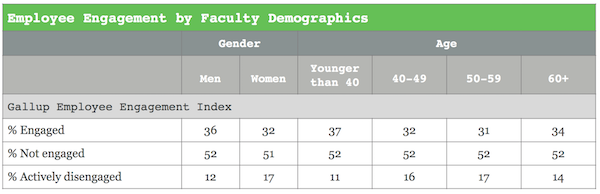

Engagement differs with age, with faculty members under 40 most likely to be engaged, at 37 percent, compared to 32 percent for faculty members in their 40s, 31 percent for those in their 50s, and 34 percent among those 60 or older.

Faculty engagement also varies somewhat by gender, with 36 percent of men being engaged versus 32 percent of women. That’s in contrast with the U.S. workforce over all, according to a 2013 Gallup study that found women were slightly more engaged than men.

Comparative Engagement

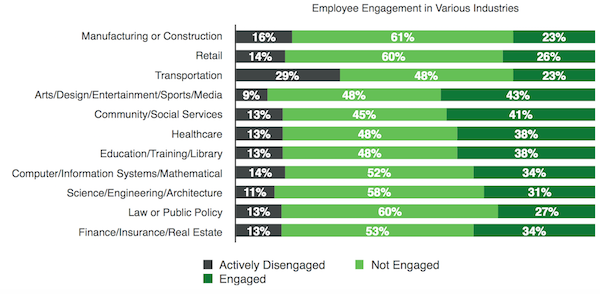

The overall faculty engagement rate is on par with the U.S. workforce as a whole, however. And faculty members are more engaged than other kinds of employees, including those in law or public policy (27 percent) or those in the science, engineering and architecture industries (31 percent). Faculty members are about as engaged as those working in the computer, information systems and math industries, but they’re less satisfied than those working in arts, design, entertainment, sports and media (43 percent), community service (41 percent), and health care (38 percent).

Regarding specific items on Gallup’s general engagement survey, faculty members are more likely than most other kinds of employees to feel that their colleagues are committed to doing quality work and that they have opportunities to learn and grow. They’re also slightly more likely to say that they believe the mission of their institutions makes them feel their job is important, that they have someone at work who cares about them as a person, and to have a best friend at work.

Faculty members receive less recognition and praise for doing work, however: just two in 10 respondents strongly agreed that they’d been commended in the last seven days. Professors are less likely than most other U.S. employees to strongly agree there’s someone at work who encourages their development. Just four in 10 professors over all said that someone’s talked to them about their progress in the last six months, for example -- a lower rate than in most other industries.

Can’t Get No Satisfaction?

Besides the standard measures Gallup uses for engagement, Inside Higher Ed added questions about job satisfaction and related issues, such as academic freedom, perceived level of respect, whether one’s opinions count, job security, dynamics with administrators and pay. Like the other metrics, faculty members rated these items on a scale of one to five, based on their level of agreement.

Faculty members were most likely to strongly agree that they have academic freedom (42 percent), feel respected for their career in and around their campus (41 percent), and believe that their opinions count in their department (40 percent).

Respondents were less likely to agree strongly that at least one administrator at their institution cares about them as a person, at 36 percent. Some 35 percent of those surveyed strongly agreed that they feel more uncertain about the future of academe than they used to and, separately, that they have job security. However, just 8 percent of faculty members strongly agreed with the idea that uncertainty about the future of higher education affects the quality of their work.

Twenty-nine percent of faculty members strongly agree that they were well trained for their position, and 25 percent strongly agree that administrators at their institution are committed to doing quality work.

Faculty members were least likely to strongly agree that their opinions seemed to count at their college or university, at 17 percent -- a sharp contrast to the level of voice they reporting having at the department level. “Faculty members appear to believe that they have more influence over what happens in their smaller, more immediate work environments than in the larger work community of which they are a part,” Gallup notes.

Respondents also were unlikely to agree strongly with the idea that they’re compensated appropriately for their work, at just 14 percent. The level of strong agreement for part-time faculty was just 10 percent.

Tenure-Track vs. Non-Tenure-Track Satisfaction

Unsurprisingly, full-time faculty members (with or without tenure) were more likely than part-timers to strongly agree that they have job security: 42 percent versus 12 percent, respectively. Differences between part- and full-time faculty responses also emerged regarding academic freedom and feeling like one’s opinion counts in the department. Some 35 percent of part-timers strongly agreed they had academic freedom compared to 43 percent of full-timers. And just 25 percent of part-timers said their opinions count, compared to 45 percent of full-timers.

The differences in strong agreement levels were even more stark based on tenure status.

Perhaps most obviously, 64 percent of tenured faculty members say they have job security, compared to 10 percent of tenure-track but not tenured and 8 percent of non-tenure-track professors. In fact, 35 percent of non-tenure-track professors strongly disagree that they have job security.

Regarding academic freedom, 53 percent of tenured faculty say they have it, while 31 percent of both tenure-track and non-tenure-track faculty members say they enjoy free inquiry.

Tenure-track and tenured faculty members both said they have a strong voice in their departments, with 44 percent and 48 percent, respectively, saying their opinions seem to count. But just 29 percent of non-tenure-track faculty members strongly agree.

Private Baccalaureate Institutions Again Fare Best

Faculty members at private nonprofit institutions are more likely than their peers at public institutions to strongly agree they have job security, at 41 percent and 29 percent, respectively.

Regarding academic freedom, professors at private institutions also are more likely to strongly agree they have it (46 percent) versus their public colleagues (37 percent). That’s perhaps unsurprising, given recent state legislative inquiries into public professors’ speech.

Private institution faculty members also say they feel respected in and around their campus at a higher rate than their peers at publics (45 percent versus 36 percent).

Continuing a trend of the most positive responses coming from faculty members at private baccalaureate institutions, Gallup notes that the private-public differences in perceived academic freedom and feeling like their opinions count are driven largely by professors at baccalaureate institutions, who strongly agree with those items at especially high rates.

The public-private differences in perceived job security, meanwhile, are related to strong agreement among private baccalaureate faculty (48 percent) and very low agreement among faculty at public associate degree-granting institutions, according to Gallup.

Hans Joerg Tiede, a professor of computer science at Illinois Wesleyan University, sits on the American Associations of University Professors’ Committee A on Academic Freedom and Tenure and recently wrote a book on the association’s history. He said the most interesting finding was the continually high response rates for engagement and satisfaction among private baccalaureate faculty compared their peers on other kinds of campuses, including both public and private doctoral- and master’s degree-granting institutions.

“One possible answer here is that private liberal arts colleges have often still a tenured majority and tend to use faculty on contingent appointments much less frequently,” he said, guessing that respondents’ tenure status was having an outsize impact on institutional results.

Delving Deeper

Tiede also said he wanted to know more about what makes faculty members think that they don’t have academic freedom.

Busteed, at Gallup, also said there’s room for further study as to why faculty members don’t report higher levels of engagement and satisfaction.

“Institutions of higher education are organizations that embrace a culture of academic freedom and shared governance -- more so than any other kind of organization,” he said. “Given that, it’s intriguing that faculty are not significantly more engaged than the average U.S. worker.”

But, he noted, “this doesn’t really tell the whole story, because we see big differences in faculty engagement across tenured, tenure-track and non-tenure-track faculty.”

Audrey J. Jaeger, professor and Alumni Distinguished Graduate Professor of education and executive director of the National Initiative for Leadership and Institutional Effectiveness at the North Carolina State University, co-wrote a recent study suggesting that part-time faculty members want respect as much as they do more material kinds of institutional supports. She said engagement and satisfaction are popular terms for students and faculty members alike, but that context matters when talking about part-time faculty members, since they’re a very diverse group.

“How I talk about engagement may resonate for an involuntary part-time faculty member at a four-year institution in the social sciences,” she said, noting that future study should include more context from which to glean important insights about the attitudes of part-time faculty members. “That same definition may not resonate with a voluntary, part-time faculty member in nursing at a community college.”

Gallup collected 2,175 web-based surveys from faculty members, for a response rate of about 10 percent (some 21,000 surveys were sent out to faculty members drawn proportionately across public and private institutions with more than 500 students). Roughly half (984) of the respondents were tenured, and half were not (1,011). The nontenured group includes 230 members on the tenure track and 781 non-tenure-track faculty members. Some 66 percent of respondents said they worked at a liberal arts institution.

Kiernan Mathews, director and principal investigator at the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education at Harvard University, pointed to the survey’s relatively low response rate, saying its effects were exacerbated by the fact that the survey itself was about engagement. He also highlighted the relatively high proportion of respondents coming from liberal arts institutions for its potential to skew some of the data.

That said, Mathews said he found it interesting that roughly equal numbers (36 percent) of full- and part-time faculty members strongly agreed with the idea that at least one administrator at their institution seemed to care. “One might expect part-time faculty to agree less often with this statement,” he said, noting that COACHE has worked particularly hard to draw administrative attention to pretenure faculty -- the group most strongly in agreement that an administrator seems to care (40 percent).

Mathews noted that tenured, pretenure and non-tenure-track faculty also tended to agree to some level that they were well trained for their duties -- good news. He also highlighted the fact that tenured faculty were the group most like to report feeling compensated at an appropriate level (with 17 percent strongly agreeing), saying it “runs contrary to some assumptions that salary compression has led to tenured faculty being underpaid and newly minted faculty pulling labor-market rates.”

Still, he said, there’s a difference between surveying attitudes about salary versus actual salaries, and COACHE has found that attitudes are influenced by campus-level equitability. In other words, he said, “Am I being compensated fairly relative to my colleagues at this institution?”