You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In the face of a national teacher shortage, colleges and universities are working to reverse a years-long enrollment decline at education programs.

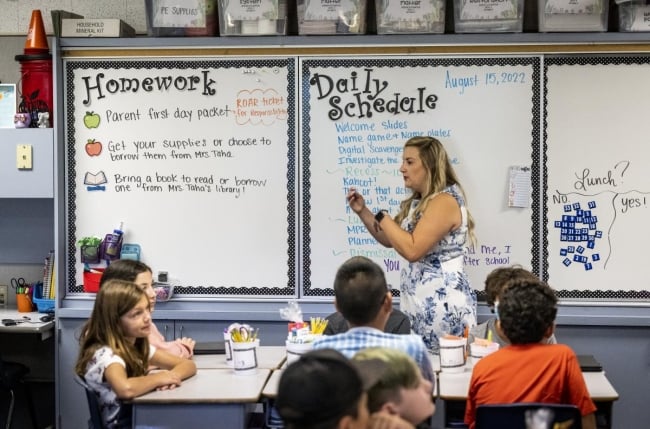

Paul Bersebach/Orange County Register/Getty Images

As the school year gets underway, a national teacher shortage has K-12 districts scrambling and job boards lengthening. The president of the National Education Association called the lack of classroom teachers a “five-alarm crisis.” Some students are returning to full-time in-person learning only to find their instructors teaching through screens, often from hundreds of miles away. Many teachers are overburdened by large classes, and in some cases, they are teaching without a degree. Some districts will start the school year with a four-day week to accommodate a lack of staff.

The flow of new teachers through the pipeline has slowed to a trickle, in part due to years of declining enrollment in education programs. Now higher education institutions are looking for ways to reverse what has become an alarming national trend.

Between 2008 and 2019, the number of students completing traditional teacher education programs in the U.S. dropped by more than a third, according to a 2022 report by the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education. The report found that the steepest declines were in degree programs in areas with the greatest need for instructors, such as bilingual education, science, math and special education.

Jacqueline King, an AACTE research, policy and advocacy consultant and co-author of the report, said teacher shortages and enrollment declines at teaching programs are “certainly correlated.” Both are closely linked to the devaluation of teaching as a profession, she added, epitomized by decades of stagnant pay, onerous workloads and political demonization.

“The wages of teachers have been absolutely flat, and the gap between them and other college-educated workers has grown,” she said. “That has contributed, over a long period of time, to declining interest in teaching as a field, both in entering degree programs and in employment.”

In some states, the enrollment drop-off for traditional teacher programs has been far steeper than the national average of 35 percent. A 2019 report by the left-leaning think tank the Center for American Progress found that from 2010 to 2018, enrollment in education programs fell by 60 percent in Illinois, nearly 70 percent in Michigan and 80 percent in Oklahoma.

Bryan Duke, interim dean of the College of Education and Professional Studies at the University of Central Oklahoma, said that while he believes the CAP report is exaggerated, institutions across his state have seen a significant enrollment dip, which he acknowledges has contributed to the current teacher shortage. Over 3,500 teacher positions in the state were unfilled as of June, according to the Oklahoma Education Association. In January, Oklahoma City University phased out its early childhood and elementary education programs due to low enrollment.

“When people consider what they study, they have that end goal in mind of what the workforce will look like, and the conditions of our schools have become unattractive to most young students,” Duke said. “When I started my career 32 years ago, we had 50, 60, 100 applications for every position at schools in the metro area. What we see now is schools will post positions and not have even one application.”

More Incentives, Fewer Barriers

To address the problem, education and teacher preparation programs at colleges and universities are experimenting with a smorgasbord of initiatives, often at the same time.

Programs are investing in expedited degree pathways for paraprofessionals already working in schools, scholarships and stipends to bolster compensation for student teachers, and enhanced partnerships with school districts and community colleges to drive up interest among potential teaching candidates.

The University of Central Oklahoma’s college of education is trying all those measures and more to attract students. Duke said that by increasing outreach to nontraditional students and offering more scholarships, the state is slowly building interest among prospective teachers. Still, the road to recovering pre-recession numbers is long.

“We are seeing results,” he said. “But—and this is really sad—we have to measure our success right now not on turning the corner on growth, but on mitigating the decline.”

State policy makers are also exploring ways to lower the barriers for students looking to enter education programs, or to qualify for a license after graduating. In May, Oklahoma axed a general competency exam for teacher candidates holding a bachelor’s degree in any subject. Iowa governor Kim Reynolds signed a law in June eliminating the requirement that teaching candidates pass the Praxis, a pre-professional skills test that was previously mandated for licensure. A similar bill passed the state Legislature in New Jersey this summer and is awaiting the governor’s signature.

Proponents of these measures say that standardized exams like the Praxis, which tests for competency in a range of subjects including math and English, are unnecessarily challenging barriers to entry to education programs and to teaching licensure.

The exams can pose an especially high hurdle for candidates of color. A 2019 report from the National Council on Teacher Quality found that 43 percent of candidates of color passed the exam on their first try, compared with 58 percent of white candidates, and that 30 percent of candidates of color didn’t retake the exam after failing the first time.

Mark McDermott, associate dean of teacher education and student services at the University of Iowa’s College of Education, said he’s looking to make degrees more accessible for students while ensuring that graduates are prepared to enter the classroom.

“It’s important to recognize barriers and to minimize those to the extent possible. But we feel teaching is really important, and it’s not an easy thing to learn to do,” he said. “We’re not just preparing teachers to be licensed; we’re preparing them to be retained and stick with teaching longer term.”

King said that while exit exams might be overly burdensome on candidates, some kind of licensure test should be required to ensure candidates are ready to enter the classroom. But, she added, the case for entrance exams to win admission to education programs is less clear.

“Given that we have this shortage, why would you set up an additional hurdle for students to get into the teacher preparation program?” she said.

‘Filling a Leaky Bucket’

Education program leaders are even more concerned by other solutions being pursued outside higher education, particularly by state officials desperate to fill teaching vacancies. Last week Florida governor Ron DeSantis announced plans to allow military veterans without college degrees to teach in public schools while they work toward earning certification. And a new Arizona law makes current undergraduate students eligible to be primary classroom teachers.

Christopher Koch, president and CEO of the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation, said that shortage or no, these measures are indicative of a broader disrespect for teaching.

“I don’t know why we’re willing to do that for teacher shortages and not for shortages in the medical professions or other professions,” he said. “It sends the wrong message about a profession where, on the one hand, we say it’s one of the most important there is, and on the other hand we say anything goes.”

Henry Tran, co-author of How Did We Get Here? The Decay of the Teaching Profession (Information Age Publishing, 2022), said that disregard for the difficulty and importance of teaching is what’s truly at the heart of the current shortage—a problem that runs deeper than higher education solutions can reach.

“There has been an overarching feeling of disrespect for the profession, both at a macro and a micro level, that leads people to leave the profession and is a barrier for entry,” said Tran, who is also a professor of educational leadership and policies at the University of South Carolina.

That feeling of disrespect has material roots. There has long been a “pay penalty” associated with teaching, compared to professions that require similar levels of education. Adjusted for inflation, teachers’ average weekly pay has increased by just $29 since 1996, according to a new report from the Economic Policy Institute; by comparison, other college graduates have seen an average increase of $445 per week over the same period. Low wages and high stress have led to a resurgence of labor organizing and militancy among teachers, including upcoming strikes planned in large districts like Columbus, Ohio, and Philadelphia.

Tran said he’s concerned that many of the proposed higher education solutions to the teacher shortages—especially lowering thresholds for licensure, like Iowa has—are “Band-Aid fixes” that won’t produce a teaching workforce with staying power.

“Ninety percent of the teacher shortage demand comes from turnover. So when you have all these solutions that are lowering standards or aiming at bringing new people in, my question is, what’s going to keep them from leaving just like the last batch?” he said. “You essentially have a leaky bucket that you’re constantly trying to fill. At some point, you’re running out of water to fill the bucket.”

King agreed that retention is a major cause of the teacher shortage. She said that whatever success teacher education programs have in increasing enrollment will be insufficient unless pay and working conditions improve.

“We’re not just going to recruit our way out of this problem,” she said. “It’s got to be a two-pronged approach.”