You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

gopixa/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Over the past two years, legislation that would ban so-called divisive concepts concerning race, gender, sexuality and U.S. history in classrooms and class assignments has spread rapidly across the nation. Legislators have introduced nearly 200 such “educational gag order” bills in 42 states. In 18 states, with a population of 118 million—about a third of all Americans—one or more such provisions are now in force. This radical legislation denies divisions that undeniably exist in U.S. society and presumes that if we sugarcoat or hide from young people the challenges we continue to confront, such divisions will miraculously disappear.

We have news for these legislators. Everything has a history, including racism, gender and sexuality. If our students do not understand these histories, they will not understand the complex world in which they live. Educators prohibited from teaching history with professional integrity cannot provide students the resources they need to become responsible citizens in a democratic society.

Most of these straitjackets are tailored for educators in elementary and secondary schools. In seven states, however, divisive concepts bans also explicitly apply to colleges and universities: Idaho, Iowa, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee and Florida, where the higher education portion of the Stop WOKE Act has been stayed temporarily by a federal judge. But even the more common strategy of focusing on supposedly impressionable younger students, often with references to “indoctrination” and age-appropriate boundaries (which are not in and of themselves illegitimate), does not spare higher education from the bludgeon.

As the Florida Department of Education’s decision to ban a new Advanced Placement course on African American studies from the state’s high schools makes clear, laws and policies that censor high school classrooms affect colleges too, albeit often indirectly. Consider concurrent-enrollment courses. In the 2010–11 school year, U.S. high schools reported about 1.4 million enrollments in courses offering dual high school and college credit in academic subjects including literature and history. Concurrent-enrollment courses are typically delivered in a high school by an instructor who is credentialed and monitored by a local college and who in many cases holds an appointment as a college faculty member.

Procedures vary widely by state and institution, but in every case these are college courses, taught by college-certified instructors, that are restricted by applicable K-12 divisive concepts laws because they are also offered for high school credit. In Texas, for instance, it’s illegal for concurrent-enrollment instructors whose courses are part of the required curriculum to “require an understanding” of The New York Times Magazine’s “1619 Project” in a U.S. History course—even if a teacher is merely asking students to compare the material with readings offering different perspectives.

In Kentucky, dual-credit U.S. history instructors are required to teach their students “that defining racial disparities solely on the legacy of [slavery] is destructive to the unification of our nation.” Defining the scope of the “legacy of slavery” is challenging indeed, but one wonders what else the legislators have in mind as foundations of racial inequality in a state whose history reflects not only the importance of slavery as an institution, but also its legacies: white supremacist terrorism, segregation and unequal distribution of public resources.

K-12 teacher training programs in colleges of education are another area where supposedly K-12–focused divisive concepts provisions can reach into the college setting. It is not always clear whether a law with a K-12 scope would extend to direct censorship of the professional preparation of teachers in college classrooms.

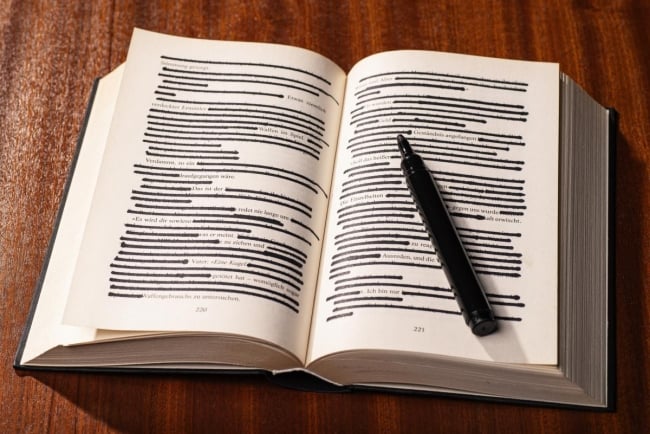

In South Dakota, however, the enforcers of divisive concepts policies are taking no chances: Executive Order 2022-02, issued by Governor Kristi Noem in April 2022, implemented a ban on divisive concepts in K-12 schools and directed the state Department of Education to review its policies and content standards. That review, in turn, led to changes in teacher preparation at the college level. In its June report, the DOE deleted from the curriculum of an Indian Studies course—a three-credit class required by law of all preservice teachers—a directive that the course “establish a fundamental awareness” of “race and gender bias, stereotyping, assumptions, etc.” To remove all doubt regarding their intentions, the report authors actually crossed out the requirement with a pen.

The next step for the DOE, according to the report, is to “engage the Board of Regents, private colleges, and tribal colleges, encouraging them to undertake a similar review [of teacher preparation programs] to ensure alignment with the EO.”

Yes, you read that right: the South Dakota Department of Education wants tribal colleges to remove information about “bias, stereotyping, assumptions, etc.” from their Indian Studies curricula for future educators. And they want public and even private colleges and universities to do the same—all because of an executive order that supposedly applies this absurd prohibition only to K-12 classrooms. No teacher with any professional historical expertise or integrity can even imply to students that American history is not rife with “bias, stereotyping, [and] assumptions” in the treatment of Native Americans.

Perhaps South Dakota represents an extreme case of how radical activists are trying to twist American education into a reactionary and procrustean version of patriotism. But it is only a short step from laws that censor teachers in K-12 schools to those that censor them in colleges and universities. Lawmakers sometimes copy legislative text from one context to the other, as they did last year in Tennessee, borrowing almost the entire text from 2021’s K-12 ban for 2022’s successful higher education legislation. And perhaps the greatest long-term consequence of K-12 censorship legislation is just beginning to reach higher education. As students leave high school classes restricted by divisive concepts laws and enter college, they are likely to be less acquainted with accurate histories of their nation and communities.

If higher education leaders and faculty hope to maintain the independence and educational quality of their institutions and to protect the democracy such institutions serve, they cannot afford to keep silent about legislation that censors their colleagues in K-12. Many have increasingly spoken out against divisive concepts legislation, even when it seems focused on the K-12 space—but more solidarity is needed. The independence and educational excellence of all American education is at stake.

And with that, the quality of democracy itself. Thomas Jefferson had it right when he insisted that public education should enable every citizen “to read, to judge and to vote understandingly on what is passing.” Laws that restrict public education about American history are laws that should not be passing at all.