You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

A major 2013 report from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences warned that at “the very moment when China and some European nations are seeking to replicate our model of broad education,” including the humanities, the U.S. was instead “narrowing” its focus and abandoning its “sense of what education has been and should continue to be.”

The paper caught the attention of policy makers, including members of Congress. Four Republicans and four Democrats asked the academy to dig deeper into the state of language education in the U.S. They wanted to know what the U.S. could do to ensure excellence in language education, especially how it might more efficiently use existing resources. They also asked how language learning influences economic growth, cultural diplomacy, productivity for future generations and a sense of personal fulfillment.

Political winds now seem even more foul to the humanities (and more inward-blowing) than they were in 2013. And many foreign language departments at all kinds of colleges and universities have found their budgets threatened and, in some cases, eliminated. But those involved in the resulting report are hopeful their findings in support of language education opportunities for all students will gain traction.

“America’s Languages: Investing in Language Education for the 21st Century,” released today, doesn’t call for “massive increases in funding at the local, state or federal levels,” said Paul LeClerc, director of Columbia University’s Global Center in Paris and chair of the academy’s Commission on Language Learning. “For the most part, we ask for sustained funding and encourage creative partnerships to increase teaching capacity, not massive government spending programs.”

The commission acknowledges its greatest challenge in making foreign language learning accessible to all students is teaching capacity, and it recommends upping the number of teachers in pre- and K-12 schools. But it hopes such instruction will be supplemented with partnerships among schools, governments, businesses and nonprofits. The Chicago Public Schools system, for example, offers an Arabic language program that's guided by Chicago's Center for Arabic Language and Culture, and supported by local Arabic speakers, local and international businesses, and the Qatar Foundation International.

The report also calls for more teaching of heritage languages spoken by immigrants to the U.S. and their families, in part to help those skills persist from one generation to the next. It urges additional, targeted support for the many Native American languages.

The commission calls, too, for more opportunities for students to learn languages -- and, with them, cultures -- abroad. One specific recommendation is to restructure federal financial aid to help students from low-income backgrounds study abroad during the summer, as well as the academic year.

As for what’s at stake in such efforts, LeClerc said having more Americans with competency in languages other than English “is essential from virtually any point of view you can think of” -- from economic growth and competitiveness to national defense to increased academic achievement and what he called “successful functioning in a global economy.”

Rosemary Feal, fellow commissioner and executive director of the Modern Language Association, was more pointed. “The greatest risk for failing to implement the key recommendations in this report is to further aggravate national isolationism,” which is not only detrimental for business purposes, she said, “but downright dangerous in an era in which immigration bans and a physical barrier with Mexico are being instituted or threatened.”

In the current political climate, Feal added, “the recommendations of the report are even more relevant than when it was commissioned.” She said language learning is one of the best ways to cultivate empathy, and the earlier in children's education the process starts, “the more likely they are to become well-functioning global citizens.”

Making the Case

The report notes that national law enforcement offices and the State and Defense Departments all have increased their foreign language capacities in recent years, citing national security. “The message in each case was clear: effective communication is the basis of international cooperation, and a strong national defense depends on our ability to understand our adversaries as well as our friends,” it says.

Regarding business, nearly 30 percent of executives say they’ve missed out on opportunities over a lack of on-staff language skills, according to a 2014 NAFSA: Association of International Educators study quoted in the report. Some 40 percent said they’d failed to reach their international potential due to language barriers.

“America’s Languages” includes profiles of professionals who’ve thrived due to their language skills -- whether they originally understood their value or not. “When I was in high school, I thought learning a foreign language was a complete waste of time and effort,” said James Tobyne, who works in strategic partnerships and business development at alibaba.com, which is often referred to as China’s Amazon.com. Yet now, he told the commission, “as an employee of one of the world’s largest internet companies, my language skills -- including proficiency in Mandarin Chinese -- are an essential component of my job.”

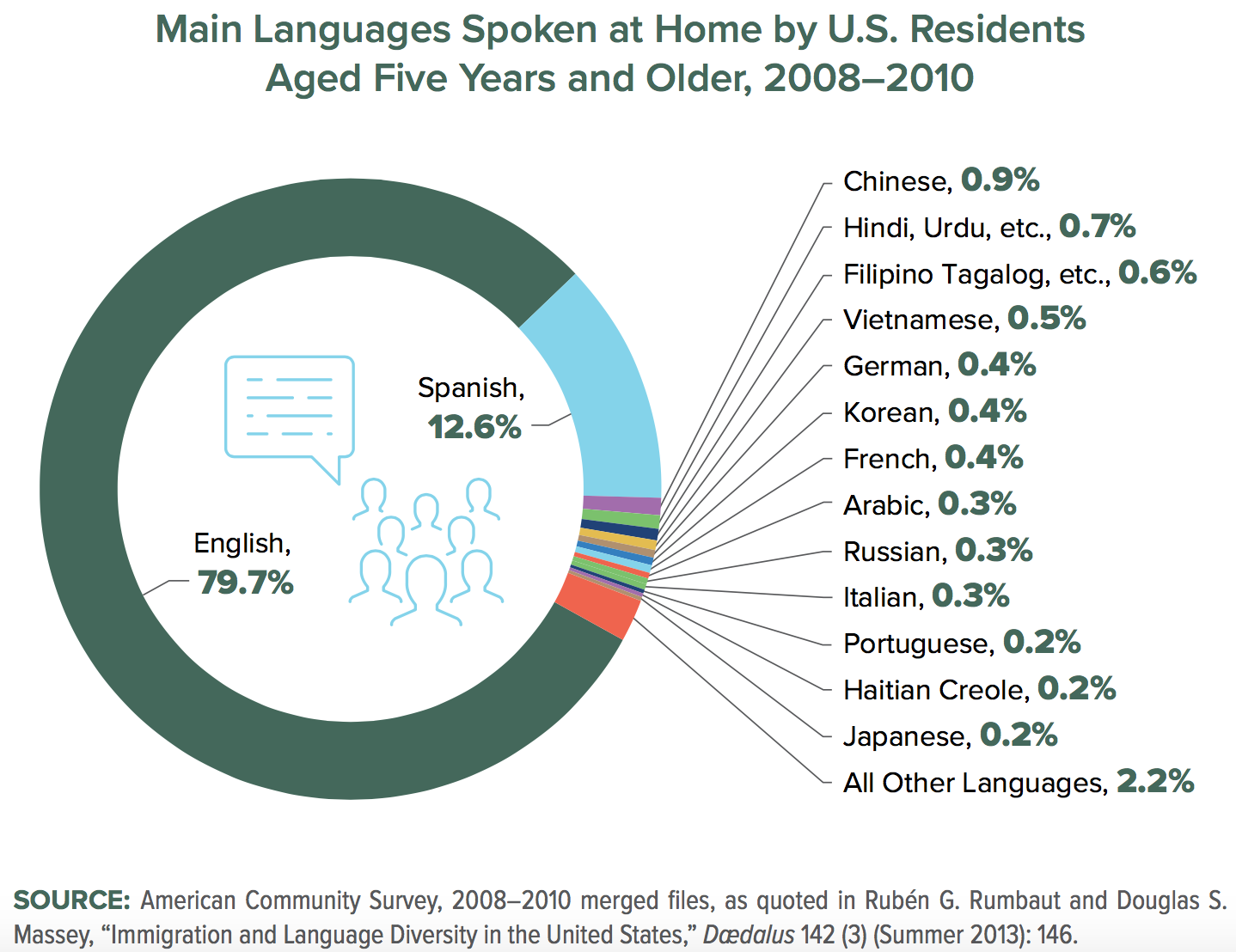

Globally, the commission says, some 300 to 400 million Chinese students are studying English, and about two-thirds of all European adults know more than one language. That’s compared to some 200,000 U.S. students studying Chinese in K-12, according to government estimates, and the approximately one-fifth of Americans who know a language other than English.

The report also calls for an expanded capacity in world languages “a social imperative,” with the provision of language access to social services mandated under Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Affordable Care Act.

“Growing numbers of American citizens speak languages other than English, and in some major urban areas, as many as half of all residents speak a non-English language at home,” it says. “But all too often, their access to vital services, including health care, and even their ability to exercise simple rights are limited not only by their inability to communicate in English,” but also by service providers’ inability to speak or secure the help of those who speak other languages.

The commission also cites additional research suggesting that foreign language study has numerous cognitive benefits for children and adults, and has been linked to higher academic achievement in other disciplines.

The academy hinted at these findings in December with a data-based national “snapshot” of U.S. language capacity, and the picture wasn’t pretty: language education is dwindling at every level, from K-12 to postsecondary, and a diminishing share of U.S. residents speak languages other than English. That’s despite an “emerging consensus among leaders in business and politics, teachers, scientists, and community members that proficiency in English is not sufficient to meet the nation’s needs,” the paper read.

According to U.S. Census Bureau data included in that report and again in “America’s Languages,” more than 60 million residents over age 5 -- or about 20 percent of the population -- speak a language other than English at home. But other research suggests that just 10 percent of the population speaks a second language proficiently, and most are "heritage speakers,” meaning they speak it for family or cultural reasons. Of those who speak a language other than English at home, 57 percent were foreign born.

Public elementary and middle school language education options have decreased within the last decade, and only a small minority of high school students are taking intermediate or advanced language courses. The number of college students enrolled in the most commonly studied languages -- with the exception of American Sign Language -- also has fallen in recent years.

Building Language Learning Capacity

Like Feal, the commission as a whole believes that instructional opportunities in other languages should be offered as early in life as possible. Its primary goal is that every school in the U.S. offer meaningful instruction of languages other than English as part of their standard curricula. The commission encourages colleges and universities to offer beginning and advanced language instruction to all students, and to reverse recent programmatic cuts "wherever possible." It also applauds recent efforts to expand undergraduate language requirements.

Some 44 states and Washington, D.C., report that they can’t find enough qualified K-12 teachers to meet current needs, but all districts respond to shortages in different ways, the commission says. It encourages further study and better data of the scope of the problem.

As for creatively increasing capacity, the commission calls for federal loan forgiveness plans to attract qualified teachers. While the federal Perkins Loan program will forgive up to 100 percent of a need-based loan for students training to become language teachers, the report says, the Education Department offers no such forgiveness for Direct Loans, offered irrespective of need.

The report also advises coordination of state credentialing systems so that qualified teachers can more easily find work in areas that need them. It imagines that technology will play a role in expanding capacity, including in offering blended-learning models in understaffed areas.

Within college and universities -- for students who wish to become language teachers and those who don’t -- the commission calls for a “recommitment” to language instruction.

While language programs were particularly vulnerable to cuts during the Great Recession, the report says, two- and four-year colleges and universities should now find new ways to provide opportunities for advanced study in languages, including through blended-learning programs and the development of new regional consortia that allow colleges and universities to pool resources. A number of such collaborations exist, including the Big Ten Academic Alliance. Fourteen member universities use a distance-learning program to offer online classes in some 65 less commonly taught languages, including Uzbek and Dutch.

Such efforts will be particularly important “as we increase the number of learning opportunities in less commonly taught languages like Arabic, Persian and Korean,” the commission wrote. “Only by maintaining such offerings in higher education can we ensure that we will have the teachers and linguistic and cultural experts we need for life and work in the 21st century.”

The report praises institutions that have instituted mandatory language study even for those undergraduates who took Advanced Placement courses in high school. Such institutions recognize that this kind of course work is “a qualification for higher-level language courses, rather than an exemption from language requirements,” the report says. “Not every college or university has the resources to institute such a policy immediately, but it is a laudable goal and worthy of serious consideration.”

The commission also encourages college and university curricula designed for Native American and heritage language speakers, and supports offering course credit for proficiency in these languages. The Spanish Heritage Language Program at the University of Houston, for example, offers specific courses for heritage Spanish speakers. Students who have successfully completed the intermediate level fulfill the university’s foreign language requirement but are encouraged to enroll in more advanced classes.

Feal said that the report strongly emphasizes a “K-16” approach, with schools working with colleges and universities to promote language learning. It also promotes as “glocal” (local-to-global) approach. Still, she said, as far as funding and other resources are concerned, the new report “outlines a clear and compelling case for the value of language learning in the postsecondary system, where language study at the most advanced levels takes place."

The report ends by saying that in the past, the U.S. has only focused on language education "in times of great need, such as encouraging Russian studies during the Cold War or instruction in certain Middle Eastern languages after the terrorist attacks of 2001." At such moments, it says, "enrollments increase dramatically, but students require years of training before they can achieve a useful level of proficiency, often long after the immediate crisis has faded and national priorities have changed."

A wiser, more forward-thinking strategy, then, "would be to steadily improve access to as many languages as possible for people of every age, ethnicity and socioeconomic background -- to treat language education as a persistent national need like competency in math or English, and to ensure that a useful level of proficiency is within every student’s reach."