You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The gathering of white supremacists, white nationalists and neo-Nazis in Charlottesville, Va., over the weekend originated -- at least on the surface -- from the groups’ opposition to the planned removal of a Confederate monument to Robert E. Lee in the college town. And although the violence in Charlottesville has subsided, Confederate monuments remain on college campuses across the South.

President Trump's criticism Tuesday of efforts to remove Confederate monuments from public spaces further inflamed tensions, and many white supremacists reported feeling emboldened afterward. Additionally, Trump spoke of a slippery slope -- that removing Confederate monuments would lead to removing monuments and statues dedicated to Thomas Jefferson or George Washington, since they owned slaves. Perhaps unknowingly, Trump in fact touched on criticisms that have been directed at the University of Virginia and the College of William and Mary, among other institutions, for their close association -- and alleged whitewashing -- of Jefferson's past.

Much of the protest movement against Confederate monuments has played out on college campuses, and it has branched out to include other historical figures who are venerated on campuses -- with building names and statues -- and in American history at large, despite their dark histories regarding race. As the coverage of Charlottesville subsides, and students across the country return to campus, those efforts can be expected to continue. In some states, however, legal roadblocks might abound, as state legislatures have taken power over public monuments and their removal, fearful that college administrations might remove them under pressure from students.

“These monuments have a gigantic bull's-eye on them,” said W. Fitzhugh Brundage, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which boasts its own controversial ties to white supremacists.

The events in Charlottesville -- and, more significantly, Brundage said, two years ago, in Charleston, S.C., where Dylann Roof killed nine people at an African-American church in hopes of starting a race war -- have also shaped the hotly debated narrative around what these monuments stand for.

“We can see these monuments are now de facto shrines for white nationalists,” Brundage said. “If you’re a white nationalist who wants to find a public space in which to profess your beliefs, what better place than a Confederate monument.”

Statues, Monuments, Buildings on Campus

Changing anything at UNC, however, remains a challenge. In 2015, a month after the Roof shooting, a law was enacted in North Carolina that vests the authority to remove public “objects of remembrance” with the state Legislature.

For UNC Chapel Hill, this includes the memorial, known as Silent Sam (below), to undergraduate students who fought for the Confederacy.

While Silent Sam might be out of UNC’s hands, the university's trustees put a self-imposed 16-year restriction on renaming buildings after a split vote changed the name of Saunders Hall to Carolina Hall. William L. Saunders, for whom the building was first named, was born in 1831 and attended UNC. He was also a prominent member and organizer of the Ku Klux Klan. Some took issue with the renaming, since other names were floated, such as Hurston Hall, which would have honored Zora Neale Hurston, a black novelist and anthropologist who audited classes at UNC from 1939 to 1940, before the university was desegregated.

The renaming freeze, which drew criticism at the time of the vote -- a month before the Roof shooting -- limits what UNC can do in light of events like Charlottesville. At the time, trustees said insulation was the point: during the freeze, UNC is working on methods to provide more historical context for Silent Sam, as well as Carolina Hall, and has launched a campaign to provide more accurate, encompassing history around the university’s ties to slavery.

Regardless, Silent Sam, as well as Aycock Residence -- named after former North Carolina governor and avowed white supremacist Charles Brantley Aycock -- will remain for the time being, to critics' dismay.

Just a few miles away, Duke University -- which, until recently, also had a building dedicated to Aycock -- is home to its own homage to the Confederacy. Among the statues adorning the entrance to the university chapel is one of Robert E. Lee.

Following the events at Charlottesville, the statue is receiving fresh scrutiny.

“As a Methodist pastor, someone who went to the school, as someone who stood in the pulpit this Sunday and took a stand against racism, it’s disheartening,” Richard Bryant, a 1999 Duke Divinity master’s program graduate, told The News & Observer in Raleigh.

How Lee got there is a mystery of sorts, and his presence has been debated since the chapel was unveiled in the 1930s, university spokesman Michael Schoenfeld told Inside Higher Ed. The chapel borrowed inspiration from the Gothic cathedrals of Europe, but, in line with Duke’s Methodist orientation, the architect swapped statues of saints for statues of figures from Protestant and Methodist traditions, as well as figures from the American South. In addition to Lee, Thomas Jefferson is also present.

“The Duke endowment board at the time … had a discussion about this,” Schoenfeld said. “And they passed a resolution that indicated that the statues ‘should be decorative, symbolic figures, and not as representing, or known as representing any specified person.’”

Although there aren’t any immediate plans to remove the statue of Lee, Schoenfeld said that the university is aware of the controversy its presence brings.

“The short answer is yes, of course, people are thinking” about Charlottesville, Schoenfeld said. “For something like this, we think it is important to study the history, and the particular context, but also to involve the university community in a thoughtful and deliberate discussion.”

“It’s not the first time that questions about, how did these statues get into the vestibule of a house of worship, in particular the chapel, and what should be done about them,” he said.

For many, removing monuments -- or renaming buildings -- is akin to erasing history, which should be remembered no matter how uncomfortable. However, at least in North Carolina, public displays of history seem to be tilted toward white supremacy.

According to a database Brundage has helped compile, there are fewer than 30 monuments dedicated to black and white North Carolinians who fought or advocated for the Union.

“It would be safe to assume there were probably somewhere in the neighborhood of 100,000 North Carolinians, who, in some way, shape or form, contributed to the Union cause in meaningful ways,” he said. “You could travel from one end of the state to the other end [today], and unless you were really looking for it, carefully … you would see nothing that acknowledges their historical contribution.”

Daina Berry, an associate professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin -- which recently removed some Confederate monuments after finding they lacked a historical connection to the university, though others remain -- also said public displays of history are imbalanced.

“What about the sons and daughters of enslaved people who survived slavery and made it out of the institution, who were on the winning side of the war?” she said. “What about monuments to honor them? What about statues and monuments to honor Native Americans … who survived the Trail of Tears?”

Thomas Jefferson

While Trump posited criticism of Jefferson as a hypothetical slippery slope, some students at UVA, which Jefferson founded, and the College of William and Mary -- where Jefferson went to college -- had already beaten him to the punch.

William and Mary was in the news in 2015 when students covered a statue of Jefferson with sticky notes, calling him a rapist and a racist. UVA has also received pushback from students for its close ties, and its president's penchant for quoting the founder.

"A university setting is the very place where civil conversations about difficult and important issues should occur. Nondestructive sticky notes are a form of expression compatible with our tradition of free expression," a William and Mary spokesman said at the time. A request for comment on the university's association with Jefferson in light of the violence at Charlottesville and Trump's most recent comments was not returned on Wednesday.

"The University of Virginia has acknowledged that controversy has been part of its history, and we continue to strive to learn from it and to improve our current environment through open and constructive dialogue," UVA spokesman Anthony P. de Bruyn said in an email. De Bruyn cited efforts such as the 2013 President's Commission on Slavery and the University, as well as the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, a proposed on-campus monument that had its design approved by UVA officials in June, as examples of addressing slavery's role and sometimes-ignored association with Jefferson and UVA.

The University of Virginia’s founder "made many contributions to the progress of the early American republic," de Bruyn said. "He served as the third president of the United States, championed religious freedom and authored the Declaration of Independence. In apparent contradiction to his persuasive arguments for liberty and human rights, however, he was also a slave owner, and he did not abolish slavery as president."

Across the Country

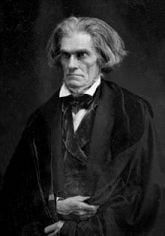

Of course, American leaders who were known racists are not just found on campuses in North Carolina, or even in the South. Yale University and Princeton University found themselves questioning their associations with the pro-slavery Senator John C. Calhoun and President Woodrow Wilson, who resegregated the federal work force, respectively.

Wilson, an alumnus of Princeton and namesake of the school of public and international affairs, has a documented history of racism, and the institution received pressure to remove his name from the school and one of its residential colleges. Addressing the issue in 2016, Princeton didn’t remove its association with Wilson but pledged to provide more context for Wilson’s history of racism in order to paint a more accurate, if uncomfortable, picture of him.

Earlier this year, Yale removed Calhoun’s name from one of its residential colleges. Calhoun, a Yale alumnus, will remain associated with other parts of the university, however.

“Unlike other namesakes on our campus, he distinguished himself not in spite of these views but because of them,” Yale president Peter Salovey said at the time. “In making this change, we must be vigilant not to erase the past. To that end, we will not remove symbols of Calhoun from elsewhere on our campus, and we will develop a plan to memorialize the fact that Calhoun was a residential college name for 86 years.”

Both Yale and Princeton have gone on to establish systems for addressing name changes, hoping to add a sense of due process and equality for all considerations going forward.

Calhoun’s name remains associated with multiple colleges in the U.S., including Clemson University in South Carolina and Calhoun Community College in Alabama.

Statues Coming Down at Bronx Community College

On Wednesday, Bronx Community College of the City University of New York announced that it would be removing two busts from the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, an outdoor monument on the college's campus. Currently there are 102 people honored there, 98 of them with busts.

A statement from Thomas A. Isekenegbe, president of the college, said that the college has always embraced "values of diversity and inclusiveness" and "creating space where all people feel respected." Consistent with those values, he said, the college will remove from the Hall of Fame the busts of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

In South Carolina, Honors for a Man Who Boasted of Killing Black People

At Clemson, the honors college remains named for Calhoun, and a spokesman said that renaming the college has not been brought up since the events at Charlottesville. Clemson and other South Carolina public colleges, like universities in North Carolina, are blocked by state law from changing the names of physical buildings, including one named after Benjamin Tillman. Tillman led a white supremacist paramilitary organization in the 1870s and boasted of personally killing African-Americans. Representing South Carolina in the governor's mansion and the U.S. Senate, he is also credited with disenfranchising African-Americans through the South Carolina Constitution of 1895.

Despite having an objectively despicable role in history, his legacy at Clemson is protected.

"Regarding Tillman Hall itself, any possible action related to the name of the building is beyond the university’s control," spokesman Mark Land said in an email. "The building is covered by the South Carolina Heritage Act, which says that no historical structures on public property can be altered or moved without a two-thirds vote in both chambers of the General Assembly."

Clemson has attempted to correct the record on Tillman -- who also has a hall named after him at Winthrop University -- in recent years, Land said.

"Regarding the legacy of Benjamin Tillman, the university has done a lot of work over the past two years, at the direction of our Board of Trustees, to tell the complete, nonromanticized and authentic history of Clemson, including stories that are hard to hear and tell. Tillman and his legacy are part of that effort."

A history task force has been created, biographies of influential South Carolinians connected to the college are "updated, detailed and frank," and plaques mark what used to be slave quarters that housed the men and women who built the university, Land said. While Tillman Hall's name won't change, the roadway in front of it has been named after Harvey Gantt, the first African-American to enroll at Clemson.

Off Campus

Though the movement against certain monuments has significant ties to campus activism, the activism has also been apparent off campus. Following the white supremacist violence in Charlottesville, the city of Baltimore took down four Confederate statues.

Among those praising the decision to remove the statues was the president of Johns Hopkins University, who noted that two were in sight of campus.

"I commend Mayor Catherine Pugh and the city council for their decision to remove Confederate monuments. We all witnessed the events in Charlottesville, Va., over the weekend, where such statues continue to be rallying points for white supremacists’ racism, and, ultimately, violence,” Ronald J. Daniels, president of Johns Hopkins University, said in a statement. “We share the belief that the statues and what they represent have no place in our city and applaud this action as a way to affirm the values of diversity, equity and inclusion that strengthen our university, our city and our nation.”

In Durham, N.C., citizens toppled a statue memorializing Confederate soldiers Monday, and earlier this year New Orleans removed the final Confederate statue in that city.

“What happened in Durham, what happened in New Orleans, what happened in Baltimore is in some ways even more significant,” Brundage said. “We had debates prior to New Orleans … but now we have communities, or people in communities, making a decision, [saying] ‘Enough of the conversation.’”

Those actions, as well as the memories of Charlottesville, will likely invigorate more campus activism -- and, potentially, conflict -- around monuments and statues, Berry said.

“The events of this weekend confirm to me that a monument does not equate to historical understanding, or even the desire to know the historical context behind the individuals that are being displayed,” she said. “I have great concern, because states like Texas have open carry, and certain campuses, like UTA, have concealed carry.”