You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

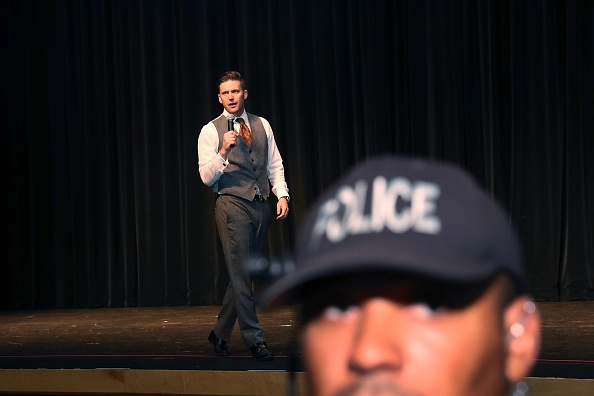

Richard Spencer speaks at Florida, with police officers monitoring the scene.

Photo by Joe Raedle / Getty Images

In August, white supremacists marched on the University of Virginia, winding around campus wielding torches and chanting Nazi refrains. The next day, a woman would die as protests in the city of Charlottesville, Va., turned violent.

University of Florida President Kent Fuchs feared a repeat of the bloodshed in Charlottesville when Richard Spencer, a figure in the right-wing fringe movement that calls itself the alt-right appeared on the campus last week.

Spencer framed the event, his first campus appearance since Charlottesville, as the free speech moment of the students’ lifetime, something that would shake the establishment and its indelible grasp on academe. He predicted a wave of at least 1,000 “antifascists,” what he called the liberal counterpart to the alt-right, who would cause campus mayhem.

But largely, because of the university’s careful planning, such a scenario was avoided, aside from a few scuffles. Two arrests were made for more minor incidents, one because a man hired by a media outlet as security brought a gun onto campus; the second was a man who resisted police orders. Three other men were arrested after Spencer had already left the campus -- they pulled up in a Jeep to a group of protesters near a bus stop and heckled them with Nazi slogans. One then fired a gunshot into the small crowd, and the Jeep sped off. All three were charged with attempted murder.

Compared to scenes in Charlottesville, this was relatively mild, to the relief of the university. And unlike many of the other events featuring controversial speakers, Spencer was able to appear -- and couldn't make himself out to be a free speech martyr.

Spencer likely won’t be halting his tour of college campuses. Colleges will need to brace for him, and other controversial conservative speakers, such as the inflammatory former Breitbart editor Milo Yiannopoulos. What can academe learn from the University of Florida?

Be prepared.

Earlier in the year, it was clear that colleges weren’t equipped or were drastically underprepared for the vehement backlash and demonstrations that some speakers would generate. The University of Virginia was operating as it would for the typical types of protests it had encountered, and after the events of Aug. 11 and 12, it outlined in a detailed report how it fell short in responding to the atypical situation. The University of California, Berkeley, also couldn’t stop the destruction of its campus in February following a planned talk by Yiannopoulos -- fires were lit, stones were thrown, Molotov cocktails hurled. (Berkeley has had more success with recent events, spending heavily on security.)

In addition to behind-the-scenes planning, the University of Florida clearly communicated everything to the public, creating a question-and-answer webpage that meticulously addressed every aspect of the event -- who Richard Spencer was and why he would be allowed to speak, the university’s views on his message and everything else down to road and bus stop closures.

In part, UF found some success because it started planning weeks ahead of the event, and it bought a little time because it denied Spencer's first request after the events of Charlottesville, citing safety concerns. But that wasn’t permanent, because …

Public higher ed institutions (almost always) can’t legally stop Spencer from speaking.

Public institutions covered by the First Amendment must accommodate speakers. They can regulate them, to a degree, and they don’t have to adhere to every request about time or date, but they must host speakers like Spencer -- the exception being if the university has in place some sort of content-neutral policy that limits who can speak on campus (more on that in a minute).

Spencer threatened to sue Florida in the weeks after it initially rejected him -- again, because it was so soon after Charlottesville. Lawyers said at the time this was likely a credible and legally sound reason to block Spencer, but only for a time.

But the institution didn’t attempt a court battle with Spencer later when he again asked to appear.

Auburn University in Alabama told Spencer no last spring, also citing safety considerations, but it was sued by a student on Spencer’s behalf -- and the student won. The judge issuing the order clearing the way for Spencer’s speech then couldn’t find any examples of concrete threats that would justify Auburn’s cancellation.

Certain policies restricting speech can pass legal muster if they’re content neutral -- such as one that requires speakers be invited by either a student group or faculty member. Texas A&M University imposed such a policy after Spencer’s visit to the campus last year. (While most public institutions appear to feel that they must let Spencer appear, Ohio State University is trying to prevent him from appearing, and a lawsuit by Spencer is expected there.)

Check your rules.

Just as Texas A&M changed its rules shortly after Spencer, some other colleges’ guidelines on outside speakers may not be designed for the likes of Richard Spencer. Such open-door policies haven’t proven problematic in recent years, but they are vulnerable now.

At the University of Florida, the amount of power given to Spencer and his crew puzzled some reporters and the public. Spencer’s group handled ticketing and approved the journalists who were allowed to cover the event -- a Florida spokeswoman said that this was consistent with leasing rules at the university, and told a Guardian reporter, "It’s their event, so they’re the ones that are allowing media in … that’s why they can have whomever they want to."

University representatives didn’t respond to a request for comment about if UF would now be reconsidering some of its polices.

You can try to convince students to stay away, but not all of them will listen.

UF President Fuchs urged students to avoid the area of the speech and the protest sites, both for their safety and because the white nationalists crave the attention.

University of Virginia President Teresa A. Sullivan did the same -- she said that it would only play into the white nationalists’ desires, and likely lead to the students being provoked into a spectacle.

Neither leaders’ pleas fully worked. Students say that standing on the sidelines doesn’t feel sufficient, and that they must confront those whose views they find abhorrent.

Simply because of the hype and potential danger, though, many Florida students who weren’t protesting stayed far away from the campus. (Thousands of protesters, some of them external to the college, did gather.)

Listen and involve your students. And let them know you care.

Though not every student was pleased with the university allowing Spencer onto campus, or the administration’s response generally, it was clear that president and the upper echelon were talking to students in the buildup to Spencer's visit and on the day he appeared.

Fuchs and the university widely promoted a student-created digital campaign under the hashtag #TogetherUF. It's a series of videos and statements on race relations on campus.

The Black Student Union released a statement plugging #TogetherUF as well, and instead of criticizing the administration directed anger toward Spencer, which has not been the case at many other institutions, where equal ire was levied toward administrators.

"Your safety and physical well-being takes precedence over the ignorance that will be spewed from the termites in the foundation of togetherness that embodies the Gator Nation," the statement reads.

Numerous gestures made clear to students that the university understood how hateful Spencer's message is, especially to members of minority groups. As Spencer arrived on campus, a professor played the civil rights anthem "Lift Every Voice and Sing" from the university's bell tower.

Separation of opposing forces is key to crowd control.

Going in, it was the university’s strategy to separate Spencer’s supporters from the protesters with physical barriers and police.

Fuchs said in an interview that most of the violence colleges have seen started not immediately before or after an event, but as the attendees headed back to their cars -- when it appears everyone has dispersed, and they’re not under the supervision of law enforcement.

The strategy of physical separation appeared to be quite successful at Florida, and seemed to minimize violence.

Proving what a powder keg campuses have become in these situations, though, when Spencer was at Auburn just a few months ago, police there were able to defuse tensions by allowing both sides to intermingle and scream at each other a bit. But that probably wouldn’t work anymore.

Now, a huge showing of law enforcement appears to be required to keep peace.

It’s expensive to pull this off successfully (for now).

And such a police presence doesn’t come cheap. As of now, the university is estimating at least $600,000 spent on security. Berkeley dropped upwards of $800,000 on security for a recent appearance by Yiannopoulos.

No college administrator knows quite how to address this problem yet. Certainly after every visit, colleges tend to re-evaluate and try to trim back costs, but no one has found a silver bullet for addressing the broader problem of stress on institutions’ bank accounts.

Kevin Kruger, president of NASPA: Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education, said institutions face a new budgetary question. How do they pay for both their core educational mission and the new expense of these costly outsiders? “It’s an expensive proposition, and there’s no easy answer.”

University administrators need to say they don’t want this. And repeat it. (Even if they're legally obligated to play host.)

Easier though, is university leadership taking a visible stand against the message of white supremacists. Fuchs did so quite successfully. When a reporter quoted Spencer saying that Fuchs “stood behind” him, Fuchs tweeted, “I don’t stand behind racist Richard Spencer. I stand with those who reject and condemn Spencer’s vile and despicable message.”

While college presidents do have a First Amendment obligation to host these speakers, their constitutional rights don’t vanish. They can say exactly how they feel, which can in a sense, reassure the campus.

Conversely, when Sullivan at the University of Virginia was first discussing Spencer and his followers’ arrival on campus, she didn’t name his group or refer to him as a white nationalist -- she was criticized then for a “raceless” response.

Controversial speakers want a riled-up crowd.

Spencer and the right-wing fringe have been quite clear -- college campuses are targets. During Spencer’s speech, a majority of the audience attending tried to drown him out with jeers and boos of “Go home.”

To Spencer, that simply played into the narrative he’s promoting -- that many college students are trying to squash freedom of expression on campus if it doesn’t align with a left-leaning point of view.

White nationalists in some cases play victim -- they’re simply trying to exercise a fundamental right, they say, and it’s the other side spurring violence and hatred. They are not the cause.

One of Spencer’s representatives took the microphone during the speech and actually thanked the crowd members, even while insinuating they had been “brainwashed” by anti-white propaganda from professors and the media.

“This right here, what you’re doing, is the best recruiting tool that you could possibly ever give us,” he said.