You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

When the American Bar Association posted a letter on its website in November saying Western Michigan University's Thomas M. Cooley Law School was not in compliance with a standard about admissions, the school slapped its accreditor with a lawsuit.

Cooley argued the ABA had acted illegally in publishing the letter, which said the law school was not in compliance with accreditation standard 501(b). That standard says law schools should only admit students who appear capable of completing legal education programs and passing the bar.

The letter to Cooley was one of more than a dozen the ABA posted about different law schools in the last 18 months, almost all citing the issue of admitting students who were not likely to succeed. Some of the other law schools promised to address the ABA’s concerns while still pointing out that their accreditation remained intact. Cooley proved more bellicose, asking a federal judge to force the accreditor to pull the letter in question from its website and withdraw copies sent to the U.S. secretary of education, the Higher Learning Commission and state regulators in Michigan and in Florida, where Cooley also has a campus.

Cooley was clearly harmed, it argued in filings made in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan. The ABA harmed Cooley's finances and reputation, the law school said.

Most sharply, though, the law school seemed to fear the reaction of students.

“WMU-Cooley also will face a loss of applications and matriculations, which are almost incalculable and certainly irreparable,” it said in court filings.

Cooley Law School’s case stands as a microcosm of developments that have been battering nonelite legal education for years. After enjoying an enrollment surge in the first decade of the new century, many law schools have more recently struggled mightily amid a dearth of jobs for young lawyers, dwindling student interest, worries schools were encouraging students to take on high debts they would struggle to repay, and intense criticism that many schools had been admitting students who never had the academic chops necessary to become practicing lawyers. At the same time, the accreditation world has been grinding toward greater transparency, placing some institutions under an unwelcome harsh light.

Resulting developments epitomize the fallout from an admissions bubble. Some schools have resisted changes in the legal education market and regulatory world. Others have moved to shrink in size or exit the market entirely. Observers worry that the most vulnerable students and minority students, who have been taken advantage of in the past, are now being shut out of law schools as the market contracts.

It all comes together in a pressure cooker, because success in legal education and the legal field is so closely tied to students passing the bar examination.

“You start with an exam that I would say is flawed,” said Deborah Jones Merritt, a professor at Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law. “And then, does it make sense any sense to tie accreditation to that exam? As much as I don’t like the exam, I think it does, because most people who go to law school want to become lawyers.”

A Contracting Market

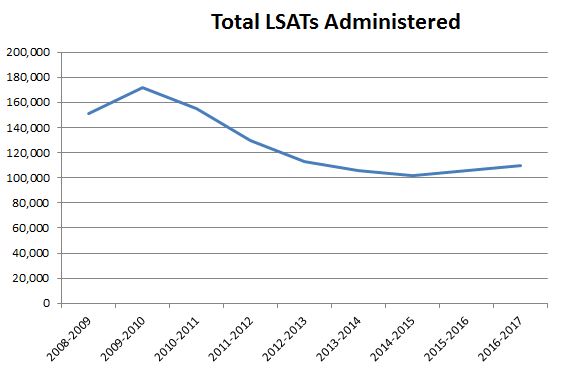

The friction is spilling out into the public eye at a particularly ironic time -- student interest in attending law schools has started rising in recent years after half a decade of brutal declines, according to Law School Admission Test data. But far fewer students take LSATs today than did several years ago. In 2016-17, a total of 109,354 LSATs were administered. In 2009-10, the number was 171,514.

Recently, several institutions have moved to get out of the law school business. Whittier College announced in April that it would close its law school. Valparaiso University said in November that its law school would stop admitting new students as it seeks to merge or move. The for-profit Charlotte School of Law shut down last year after it was placed on probation by the ABA, lost access to federal Title IV funding and lost its license to operate in North Carolina.

The ABA has approved new law schools as recently as 2017, but signs point to future contraction driven by market forces. Experts predict the contraction will come not among the largest, most prestigious institutions, but among small, private law schools that are already struggling to enroll enough students who can pass the bar.

To understand why, start with the fact that the legal education market is driven in many ways by prestige and competition. Admitted students’ scores on the LSAT are considered extremely important, in part because of a fixation on rankings and in part because LSAT advocates consider scores on the test to be the best indicator of whether students can pass the bar after graduation.

Add in a heightened focus on student outcomes -- which in the law field largely hinge on whether schools’ graduates pass the bar. Add in also changes in the types of jobs available for lawyers as technology and other developments change the labor market so that more legal work can be completed by nonlawyers. Then remember the drop in the number of students taking the LSAT.

It all boils down to a smaller applicant pool and a market in which top law schools suck up a greater share of the best students.

“There are no surprises here,” said Robert Zemsky, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the founder of its Institute for Research on Higher Education.

“The rich schools are spending all the money on student aid,” Zemsky said. “The very top of the market just said, ‘We are going to preserve the status quo, and if it costs us money, so be it.’”

Such a development can have significant impacts farther down in the market. Small, less prestigious law schools have complained that their best students transfer out after a year, chasing a diploma emblazoned with a more prestigious school’s name. Some schools find themselves facing the unsavory choice of admitting more students who might not be able to pass the bar or not admitting enough tuition-paying students to keep the doors open.

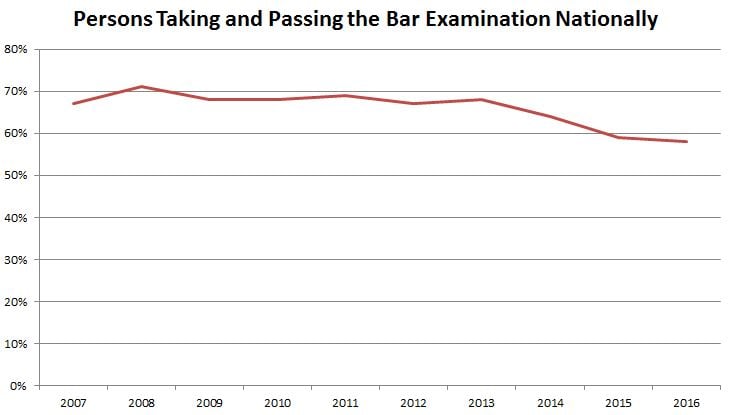

For those who believe in a direct correlation between the LSAT and bar passage rates, the decline in LSAT takers seems to have translated into a higher number of students attending law school who were subsequently unable to pass the bar. A greater portion of students started struggling to pass the bar a few years ago.

Nationwide, between 67 percent and 71 percent of individuals taking the bar each year used to pass, according to data from the National Conference of Bar Examiners. Pass rates started slipping several years ago, though -- right around the time when students admitted in years with sharply fewer LSAT takers would have been graduating and passing the bar. In 2014, 64 percent of those taking the bar passed. In 2015, only 59 percent passed. In 2016, just 58 percent did.

Schools Slimming Down

A group of law schools run by the for-profit InfiLaw System received perhaps the most negative press of any institutions for admitting too many students who arguably hadn’t demonstrated the academic ability to graduate and pass the bar -- and then hiring those same students, allegedly to prop up postgraduation employment statistics. Putting aside the issue of past behavior, the actions of those schools more recently provides insight into the law school market’s reaction to past difficulties.

In 2011, the Florida Coastal School of Law, an InfiLaw institution, offered admission to 3,493 students, or 66 percent of its applicants, according to the ABA. Of those admitted, 671 matriculated. Their median LSAT score was 147. By almost any measure, this was a low score. Approximately two-thirds of those taking the LSAT in recent years have scored higher than 147. Only seven ABA-accredited law schools enrolled classes with lower median LSAT scores that year. Students enrolling in elite law schools post much higher scores -- Yale Law School's median LSAT score was 173 in 2011. Nonelite public law schools also tended to enroll classes with median LSAT scores above 150 -- the University of North Dakota's was 151, and the University of Pittsburgh's was 159.

Six years later, Florida Coastal was receiving about a quarter of the applicants as it had in 2011. But it was admitting a smaller portion -- 46 percent. Only 97 enrolled. The median LSAT score, which had dropped below 2011 levels in recent years, rebounded to 148 in 2017.

The school has been focused on increasing the enrollment credentials of its incoming classes, according to its dean, Scott DeVito. He has argued that the college raised its bottom-quartile LSAT score from 141 in 2016 to 145 in 2017, pushing the indicator above scores posted by 22 other law schools in 2016. He also said he believes Florida Coastal is fully compliant with ABA standards.

“Our approach has been to single-mindedly focus on increasing incoming credentials, recognizing that it will decrease our overall enrollment,” he wrote in an email. “This has been extremely painful for faculty and staff who have been asked to leave the school, and, because they have always put the students first, those faculty and staff have been extraordinarily professional and supportive of the changes despite the impact it has had on their professional lives.”

Florida Coastal shares the strategy with its sister InfiLaw institution, Arizona Summit Law School. In 2011, Arizona Summit -- which was then called Phoenix School of Law -- offered admission to 1,677 students, or 73 percent of its applicants. A total of 450 matriculated. Its median LSAT score was 148.

In 2017, Arizona Summit received just 24 percent of the applications it had six years before. It admitted fewer, 47 percent. Just 49 enrolled, although their median LSAT score matched that of 2011 at 148.

Arizona Summit has become more risk averse when admitting students, said Donald Lively, president of the law school. Certain bar outcomes are largely preordained for students at some LSAT scores, he said. So when a law school becomes risk averse, it stops admitting students on the fringes academically.

“You have to modulate your efforts to bring in people who, if you give them the support, the program, the attention they need, you know they can be successful,” he said.

To some of InfiLaw’s most outspoken critics, these might sound like necessary changes after the schools allegedly spent years collecting tuition from students who had little chance of passing the bar. Still, incoming classes’ undergraduate grade point averages have eroded, even as LSAT scores have recovered. Arizona Summit’s first-year class posted a median undergraduate GPA of 2.81 in 2017, down from 3.05 in 2011. Florida Coastal’s was 2.83 in 2017, down from 3.08. These are relatively low GPAs for incoming classes at law schools -- only a dozen ABA-accredited law schools that enrolled new classes in 2017 reported classes with a median undergraduate GPA below 3.0.

At some points in the past, Arizona Summit made decisions that weren’t geared toward helping its enrolled students pass the bar, Lively said. Several years ago, it decided to make upper-division bar test courses nonmandatory so that students would have the opportunity to take more courses intended to develop practical skills. It wasn’t that the law school had bad intentions, Lively said. It wanted its students to be practice ready as soon as possible.

“There were times when, to be candid, our academic support systems were not functional at the level they needed to be to enable people to achieve the level of success they were capable of,” he said.

The InfiLaw System isn’t just a leading example of law schools shrinking. It’s an example of them closing, attempting to merge, and being hit with accreditation decisions.

Arizona Summit announced plans earlier this year to affiliate with Bethune-Cookman University. That idea has since been scrapped, but the law school's leaders have signed a memorandum of understanding for a deal that would have Arizona Summit becoming a part of another yet-to-be-disclosed nonprofit institution, Lively said. Florida Coastal, meanwhile, has been exploring affiliations with nonprofit universities or a change to nonprofit status for at least three years, according to its dean, DeVito.

The third InfiLaw school is the Charlotte School of Law, which shut down earlier this year. The immediate chain of events that led to its closure started when the ABA placed the school on probation in 2016, citing standards on preparing students for admission to the bar and participation in the legal field, sound admissions policies, and admitting only applicants who appeared able to pass the bar.

Arizona Summit was placed on probation earlier this year because of some of the same standards on academic rigor and admissions, along with standards relating to academics and support. In December the ABA also found it out of compliance with a standard about adequate finances. Florida Coastal has been notified that it was not in compliance with standards on rigor, academic support and admissions as well, but it was not placed on probation. The ABA posted letters on its website about all three.

An Active ABA

The InfiLaw schools are not alone in being publicly scrutinized by the ABA. Between June 2016 and December 2017, the accreditor notified 11 law schools that they had been censured, placed on probation, found to be out of compliance with standards or that they needed to take remedial action. Since then, it has notified one more. It has publicly posted letters about the findings starting in August 2016.

The schools are Ave Maria School of Law, Valparaiso University School of Law, Appalachian School of Law, the State University of New York University at Buffalo School of Law, Thomas Jefferson School of Law, Texas Southern University Thurgood Marshall School of Law, Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School, Cooley School of Law, North Carolina Central University School of Law and the InfiLaw schools. Standards involving admissions were invoked in nearly every case, although some schools were also cited for standards relating to academic rigor, finances, furnishing information and, in the case of Texas Southern, fostering opportunity without discrimination. The ABA did not point to admissions standards in a letter to SUNY Buffalo, instead citing standards related to financial resources and record keeping.

With only a few exceptions, the law schools are still accredited and should have the chance to bring themselves into compliance. Now-closed Charlotte is one exception. Another is Valparaiso, but not because it still faces accreditation issues. The ABA found Valparaiso in compliance with standards this year after censuring it for admissions practices in 2016.

In many cases, institutions the ABA has named in accreditation activity have sent letters to students or responded publicly that they expect to remain open and show that they fully comply with standards.

For instance, Thomas Jefferson School of Law put out a statement from Dean Joan Bullock saying the law school had been accused of no misconduct and that it would remain accredited. The ABA posted notice in November that Thomas Jefferson was being placed on probation over standards related to finances, academics and admissions.

“While we are disappointed with the council’s decision, we are addressing the ABA’s concerns,” Bullock’s letter said. “Thomas Jefferson School of Law will continue its unwavering commitment to providing our students with the knowledge and skills to excel as law students, pass the bar, and succeed in their professional careers. As it has over the past few years, we will continue to steadily improve our financial stability to best serve our students.”

The ABA hasn’t necessarily been enforcing accreditation standards more stringently in the last 18 months. Data maintained by the Department of Education on accreditation suggest that the ABA had previously placed law schools on show-cause status without publicly posting the decisions on its website. The department listed several institutions as being placed on or removed from show-cause status in 2016 and early 2017, but the webpages where the ABA has been posting letters recently did not reference those cases.

Now, the ABA is publicly posting about its actions in cases where it may not have in the past.

“The public postings are, basically, what follows under our rules when schools get to a certain step in the enforcement process,” said Barry Currier, managing director of the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, in an email.

“The public postings are, basically, what follows under our rules when schools get to a certain step in the enforcement process,” said Barry Currier, managing director of the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, in an email.

“The U.S. Department of Education has also modified its directives about what needs to be publicly reported, and at what point in the process that needs to happen,” he said. “We are following its requirements, as we must.”

Yet a significant number of the 205 ABA-approved law schools have been found out of compliance with standards, censured or placed on probation in the last 18 months. Asked to interpret that fact, Currier pointed to a market that has challenged law schools even as they attempt to adapt and create new programming. The council and accreditation committee are simply doing their jobs and enforcing current standards, he said.

This is where Cooley Law School’s court case was important. After Cooley argued that the ABA harmed it by publicly posting letters about accreditation noncompliance, the ABA replied, in part, that it had no choice but to do so under Department of Education guidance. In court filings, it cited a November 2016 letter from then Under Secretary of Education Ted Mitchell.

That letter spelled out the cases in which accreditors are expected to notify the Department of Education, state licensing agencies and the public of actions they take.

Last month, Senior U.S. District Judge Arthur J. Tarnow denied the law school’s request for an injunction that would have forced the ABA to take down the letter. Cooley can continue to litigate its claim, he ruled. But the law school failed to meet the burden needed to win an injunction, which would harm the ABA’s accreditation process and hurt students.

“An order requiring the ABA to retract truthful information from the public will harm prospective law students who are in the midst of the application process,” Tarnow wrote. “Withdrawing the letter may also mislead prospective students into believing that the ABA has found Cooley in compliance with all of its Standards.”

Tarnow also wrote that Cooley’s decision to bring the lawsuit -- which was covered extensively in the legal press -- was the primary cause of any harm to its reputation. Students had already drawn conclusions about the law school because of the suit, Tarnow added.

An ABA spokesman said the accreditor is pleased with the decision but declined further comment. Cooley’s general counsel and associate dean of external affairs, James D. Robb, noted that the court said the law school is able to continue pursuing the litigation. It intends to do so.

Robb had spoken to Inside Higher Ed before the judge’s decision, speaking at length about changes in the market for legal education and the tensions they expose.

Extinguishing Dreams?

Cooley counts its mission as providing access to and opportunity for legal education. It’s similar to the ideals many small and independent law schools espouse: they may enroll students who don’t get top marks on the LSAT, but in doing so, they give students from groups who traditionally have not attended law school a chance to become lawyers.

“I think a lot of schools say they want diverse student bodies, and that’s wonderful, but I’m not sure they’re admitting a diverse student body,” Robb said. “We take a lot of criticism for who we admit. We don’t take a lot of criticism for what we do with the students once they get here.”

Cooley, remember, was cited for ABA standard 501(b) -- that law schools should only admit applicants who appear capable of satisfactorily completing legal education programs and passing the bar.

The law school’s first-year classes have generally posted a median LSAT score in the mid- to low 140s in recent years, according to ABA reports. Their median undergraduate GPA has been about 3.0.

Statistics on the Michigan Bar Examination show a smaller percentage of Cooley students pass than the state average. But Cooley’s first-time test takers tend to come close to the state average pass rate on bar exams administered in February.

In the February 2017 Michigan Bar Examination, 65 percent of Cooley’s first-time test takers passed, compared to 67 percent of all first-time applicants statewide. Just 39 percent of all Cooley test takers passed, compared to 49 percent of everyone in the state. In July 2017, 53 percent of Cooley’s first-time test takers passed, compared to 78 percent of all first-time test takers in Michigan. Only 50 percent of all of Cooley test takers passed, versus 73 percent of total applicants.

“Should we adopt the paternalistic approach to protect these students from themselves, denying them the opportunity to prove themselves?” he wrote. “Should we allow the results of one brief test to determine a student’s destiny? Should we extinguish a dream based on a single factor, like an LSAT score?”

Regardless of lofty goals, ABA statistics make it clear that Cooley has diminished in size in recent years. In 2011, it offered admission to 80 percent of 4,032 applicants, with 1,161 matriculating. In 2017 it offered admission to 86 percent of 1,295 applicants. Only 424 enrolled.

Critics still argue there are too many law schools struggling financially that have made a practice of admitting students who appear unable to pass the bar. An important question is whether it’s reasonable to expect schools to shrink, close or take other drastic action instead of following ethically gray admissions practices. Another is whether accreditors should do more to prevent schools from utilizing those questionable practices -- or should have done more in the past.

And would the benefits to students outweigh the expected negative effects on access?

“Policy making is about trade-offs,” said Kyle McEntee, co-founder and executive director of the nonprofit group Law School Transparency. “The question is not, ‘Does the school do any good?’ Because it does. All schools do some good. The question is whether they do more good than harm.”

McEntee also suggested another solution to the access problem. High-end law schools -- those with the most resources that could theoretically best support students on the edge -- could take on more risk. They could admit more first-generation students, minority students, nontraditional students and students with marginal test scores.

Of course, legal education doesn’t only serve students. It also serves employers who need lawyers and people who need to access legal services. So the equation about how many lawyers schools should turn out, whom they should admit and how they should train them is complex. So is the way it is distilled at the accreditor level.

“Is this system set up in a way that does the most for justice and access for the profession?” McEntee said. “I just don’t think it is, and that’s why we’re willing to break it up a little bit at the bottom rungs, to say we can do better than this.”

Some would say the system is working.

“The accreditation committee and the council have taken appropriate steps to require schools that have been operating out of compliance with the standards to come into compliance, or to face sanctions if they do not,” wrote Currier, of the ABA. “The council is considering changes to allow the accreditation process to move with more dispatch. But, in general, the first step the council has taken when it has concerns about a school is providing the school with an opportunity to bring itself back into compliance. That seems an appropriate step to take.”