You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Research has shown that the more college credits students take per term, the more likely they are to graduate -- and on time.

Many colleges and states have responded to those findings and implemented new programs, offered incentives and enacted policy that encourage students to pursue at least 12 college credits per semester to graduate on time within two or four years. But every student can't attend college full-time.

That recognition led Bunker Hill Community College to refocus how instructors and advisers engage part-time students. The college started requiring the students to take learning community seminars and then adapted the seminars to fit the needs of students.

A report from the Center for American Progress found that the seminars specifically increased retention and persistence among part-time students. Marcella Bombardieri, a senior analyst at CAP who authored the report, said Bunker Hill could be a model for other colleges across the country looking to improve part-time student performance.

Although offering learning communities and accommodating students' schedules isn't new or unique, especially in a community college setting, what Bunker Hill is doing is different.

"The biggest thing that is different is that part-time students are targeted," said Bombardieri, who has been approached by several organizations interested in Bunker Hill's model since the report was released. "That's who they're paying attention to and that's what distinguishes them from a lot of the conversation about increasing completion."

There have been a few initiatives around the country directed at helping part-time students, but they've mostly focused on increasing the number of credits students earn and encouraging them to attend college full-time, she said. Bombardieri cited the City University of New York's well-regarded Accelerated Study in Associate Programs as one example.

Evelyn Waiwaiole, executive director of the Center for Community College Student Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin, also considers CUNY's program beneficial. But when it comes to helping part-time students who plan to continue attending only part-time, she said the typical approaches she hears from colleges are that they stay open later and provide services that accommodate students' schedules.

"When students are connected, they are engaged," she said in an email. "If students are in learning communities, they are connected to their peers. It's no surprise the outcomes are changing."

There are other colleges that have restructured how they offer classes in order to help part-time students. Trident Technical College in South Carolina, for instance, altered courses by dividing semesters into seven-week periods. Furthermore, if students at Trident Tech choose to withdraw after seven weeks, they don't lose the credits they accumulated.

Odessa College in Texas uses eight weeks of accelerated learning instead of the traditional 16 weeks to increase academic outcomes for part-time students, said Karen Stout, president and chief executive officer of Achieving the Dream, a completion-focused nonprofit group, of which Bunker Hill is a member institution.

"What's interesting about Bunker Hill's work is that it's inside the classroom," she said. "It's the designing and linkage of courses that's exciting."

Stout has been critical of initiatives that solely work to encourage part-time students to take on more credits than they can handle.

"This data from Bunker Hill is promising and presents a lot of questions," she said. "Can we go further with the intentional design of the part-time student experience that borrows from the best high-impact practices that work for full-time students in the learning community design?"

At Bunker Hill, students attend the seminars, for which they can earn college credit, for a few hours each week to study a single topic or theme that is relevant to their major or life experiences. The seminar topics may range from Becoming a Teacher to Parents as First Teachers, Sports Psychology: Success in Sports & Life, or Latinas: A Culture of Empowerment.

The seminars are culturally relevant, rigorous and tied into student supports, said Lori Catallozzi, dean of humanities and learning communities at Bunker Hill.

“They give part-time students more of an advantage because they won’t get that anywhere else from the college.”

While these seminars have long shown academic benefits for full-time students, in 2013 Bunker Hill began requiring first-year students with at least a nine-credit course load to also attend the seminars after administrators saw higher rates of students re-enrolling.

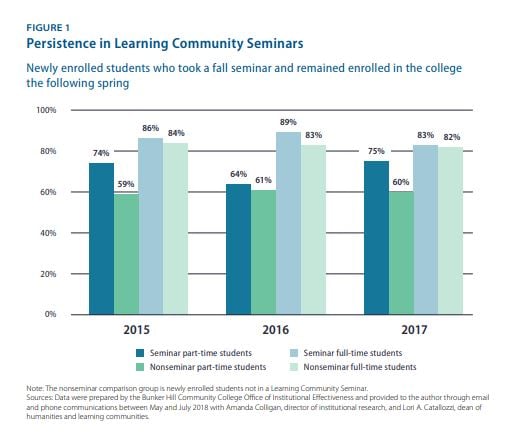

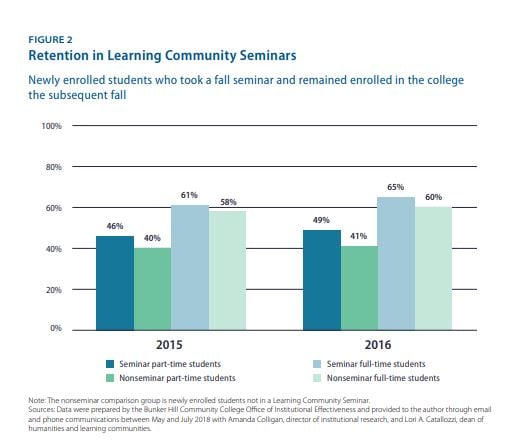

For instance, in 2017, 75 percent of part-time students who attended a fall seminar remained enrolled in the college the following spring, compared to 60 percent of part-time students that did not attend a seminar. In 2016, 49 percent of part-time students who enrolled in a seminar re-enrolled in the college the next year compared to 41 percent of part-time students that did not attend a seminar, according to data from the college.

About 4,700 of Bunker Hill’s nearly 14,000 students enrolled in a learning community seminar last year. More than 2,100 students were part-time for at least one of the semesters during which they took a seminar. About 65 percent of the college’s overall enrollment is part-time.

In Bunker Hill’s learning community seminars, student mentors participate in every class and help their peers with issues that arise outside the classroom, such as problems with off-campus housing. Success coaches are also on hand to help students develop their career skills or map academic plans.

“When I think about the life of a part-time student here, they’re more likely to come for a couple of classes and then they’re leaving for family reasons … leaving for full-time jobs,” Catallozzi said. “Their lives are more complex and fuller than full-time students'. If they’re going to benefit from support services or a sense of integration with the college, or relationships with faculty or peers, it’ll happen in the classroom.”

Some part-time students who come to the Boston campus in the evenings and on weekends may find student advising or support offices understaffed or closed. But success coaches or academic advisers are always present and available to students in the seminars, said Arlene Vallie, director of learning communities at Bunker Hill.

“Those are the things that make a difference,” she said.

Bunker Hill offers three types of seminars in the evenings and on weekends to accommodate the schedules of part-time students.

One seminar focuses on a topic that may be of interest to students and includes a peer mentor and success coach who works alongside the instructor. Another learning community is taught as a "cluster" seminar where a group of students takes two courses together in the same semester and the professors coordinate and plan their instruction around common themes. The college recently introduced the success coaches and peer mentors to the cluster seminars. The third seminar is a professional studies community, which is available for students majoring in fields such as information technology or nursing. These students are required to take the professional seminar as part of their degree plan, and they are also paired with coaches and mentors.

Bombardieri said that while increasing enrollment and getting students to take more classes is a worthy goal, she and her colleagues are concerned that the push to increase the number of full-time students excludes those students for whom attending part-time is the only option.

A report last year from CAP indicated that part-time students are often overlooked by colleges and policy makers. The report showed that about one-quarter of exclusively part-time students graduate and slightly more than half of the students who attend part-time during their college career earn a degree. Meanwhile, 80 percent of exclusively full-time students attain a degree.

“When I talk to people in the community college, they generally say, ‘Most of our students are part-time and everything we do is for part-time [students],’” Bombardieri said. “I know they mean that, but at the same time they aren’t necessarily looking specifically at that population and how their needs might be different.”

The challenge for Bunker Hill administrators is taking what they know works and expanding it to more students, Bombardieri said. She said it would also be interesting to look at the effect of learning communities on part-time graduation and transfer rates.

Although Bunker Hill is still analyzing the data in the CAP report, Catallozzi said discussions are underway about expanding the learning community requirement to students who are enrolled in classes totaling at least six credits, and adding internships and apprenticeships as components.