You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A large majority of humanities Ph.D.s believe that their graduate programs prepared them well for their eventual jobs, academic or not, especially over time. And all those jobs appear to require many of the same kinds of skills, according to a new report from the Council of Graduate Schools.

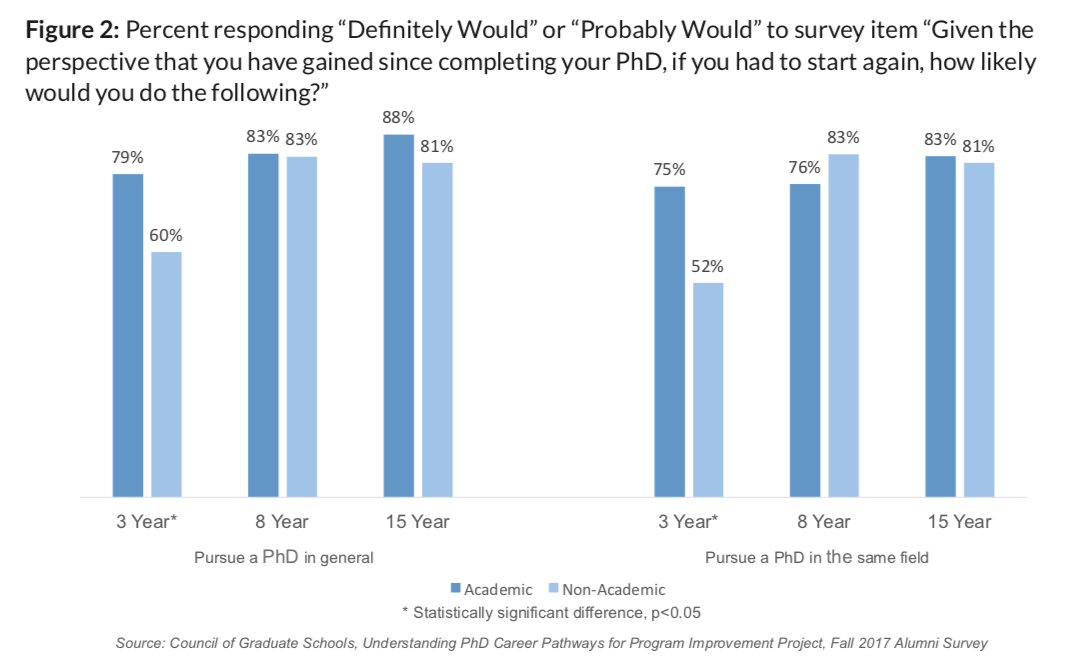

A majority of Ph.D.s surveyed as part of the council's research also said they would pursue a doctorate in the same general field if they had to do it all over again -- good news for both institutions and current students looking for light at the end of the graduate school tunnel. The findings seemingly defy the tight academic job market in many humanities fields and widespread reports that recent Ph.D.s see few tenure-track positions available.

Satisfaction with Ph.D. training was greatest among those who earned their doctorates at least 15 years ago, but majorities of those who earned Ph.D.s more recently also agreed they'd enroll in graduate school again.

“Together, these results suggest that humanities Ph.D. education offers relevant training that prepares graduates for jobs both inside and outside of the academy,” reads the council’s report, the first in a series of briefs based on its Ph.D. Careers Pathways project on graduate program outcomes. The council encourages programs and institutions to “continue to offer curricular and co-curricular experiences that integrate training and professional development opportunities toward a variety of fulfilling career paths.”

Emily Swafford, director of academic and professional affairs at the American Historical Association, said the council’s data on attitudes and skills complement the information her association already has collected via its own career-tracking efforts. The council’s work is also “exciting” in that its data show not only where humanities Ph.D. work, but what that work “looks like and how they feel about it," she said.

“It's the only project I know of that is collecting that kind of data on a large scale.”

Why We Need More Data

Paula Krebs, executive director of the Modern Language Association, which has its own Ph.D.-tracking initiative, said the council report affirms the MLA’s belief that humanities Ph.D.s give students “skills they can use in a variety of careers.”

Doctoral programs need not develop “separate paths aimed at academic and nonacademic employment,” she said. And the most successful programs “help students to understand and be articulate about the skills, values and perspectives they've gained in their doctoral work,” Krebs added. That way, students who do become professors can help their own students understand the value of the humanities relative to diverse careers, and those who work outside academe will be more successful interviewees.

Considering the investment of time and resources that graduate school is, we know surprisingly little about its returns. As Swafford pointed out, there is no comprehensive national data set on where Ph.D.s across disciplines end up working and how prepared and rewarded they feel. Individual institutions, professional associations and other organizations have attempted to fill the data gap, but the picture is still hazy -- especially for humanities Ph.D.s.

That’s starting to change, however. The Association of American Universities is pushing for institutional transparency about who gets Ph.D.s in what length of time and what they end up doing, for example.

Via its own pathways project, the council is gathering data on career tracks and professional preparation from dozens of institutions. The new report is based on a survey of Ph.D.s who were three, eight or 15 years out of their programs at 35 participating institutions. The aggregated data set includes responses from 882 Ph.D.s in the following fields: anthropology and archaeology, English, foreign languages, history, philosophy, religion and theology, and humanities/other. The analysis focused on alumni working in jobs closely or somewhat related to their academic fields, but only 60 respondents fell outside that group.

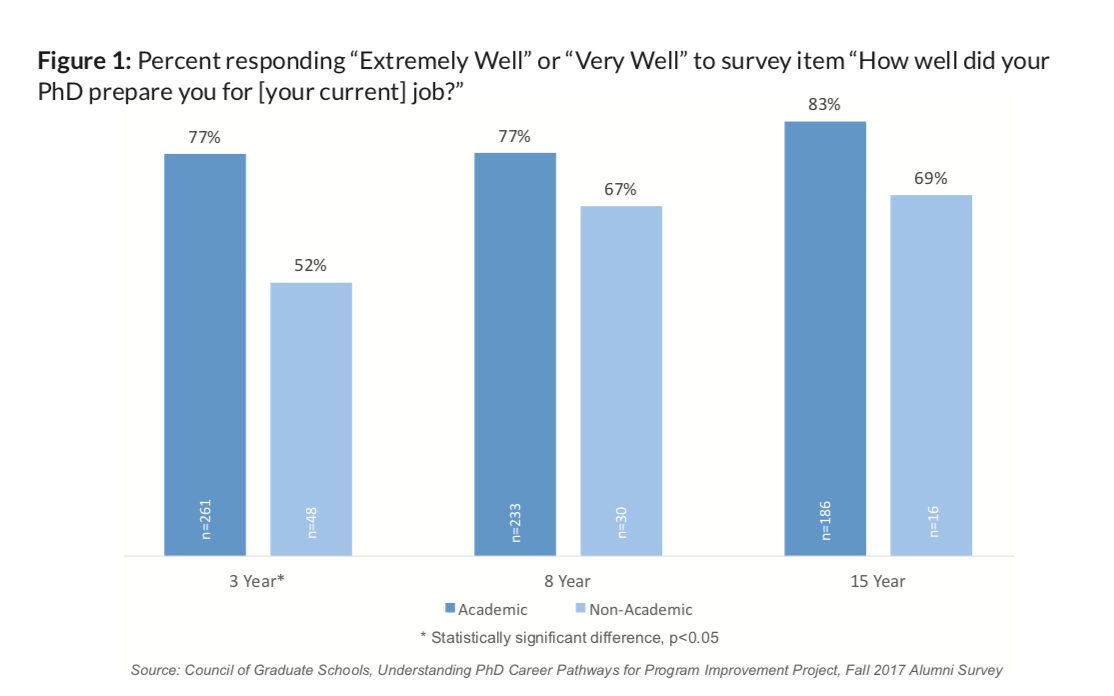

Feeling Prepared, Especially Over Time

The council found that humanities Ph.D.s employed by colleges and universities felt that their studies had better prepared them for their work than their counterparts working outside academe. More precisely, three years post-Ph.D., some 52 percent of humanists working in nonacademic jobs said their programs prepared them well for work, compared to 77 percent of those working in academe. But that difference narrowed to statistical insignificance by eight and 15 years post-Ph.D. The same went for whether Ph.D.s would pursue the same training in hindsight.

"For those employed in business, nonprofit, government and other sectors, it may take longer to recognize the value and relevance of Ph.D. training to careers,” reads the brief. “Recent graduates may also be reconciling their initial expectations for a first job and career (e.g., becoming a faculty member at a research university) with their actual employment (e.g., employed in another academic or nonacademic context). Support for transitions into first jobs may be particularly helpful for recent graduates.”

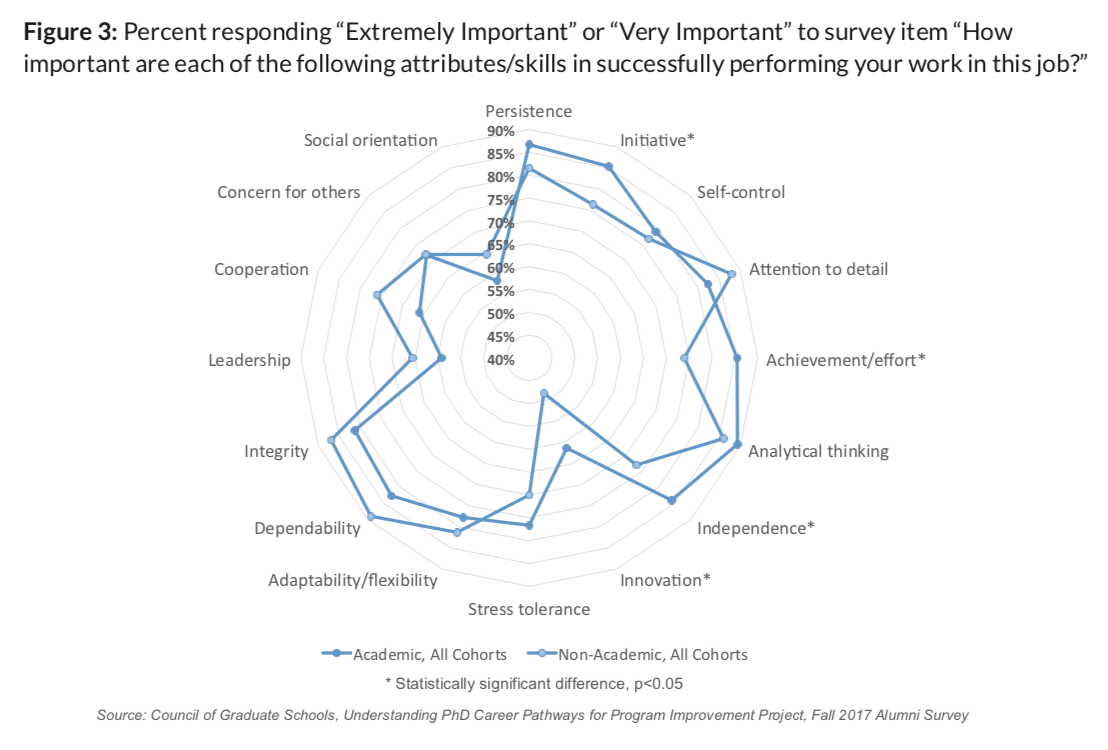

Asked whether various skills and attributes were extremely or very important to their jobs, academic and nonacademic workers responded similarly, with some significant differences. Important traits for both groups included persistence, attention to detail, analytical thinking, dependability and integrity.

Regarding employers, the report says that the “value of a humanities Ph.D.s might not be immediately tangible to employers outside of the academy,” so it’s “important for universities to engage employers as partners, helping them to understand the skills and knowledge humanities Ph.D.s offer to their sectors.”

‘The Transition Was Hard’

Swafford said the finding that most humanists eventually feel comfortable about how their Ph.D.s prepared them for work “corroborates what we've heard from historians working beyond the professoriate -- that the transition was hard, but there is something valuable enough about earning their Ph.D. that they would do it again if they had the choice.”

Robert Townsend, who has studied humanities career outcomes as director of the Washington office of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, noted that his organization’s analyses show that Ph.D.s employed outside academe were somewhat less satisfied than their academic peers. So the council’s finding that that gap narrows over time stands out to him, as well, he said -- though it remains “an open question whether Ph.D.s in nonacademic careers gain confidence in the relationship between their degree and their jobs, or they work their way into jobs that more directly relate to the degree.” Such a distinction has important implications for departments and organizations working to promote career diversity, he said.

Suzanne Ortega, council president, said in a statement that it’s not clear from the data just why the gap narrows. Whatever the reason, she said, “this is good evidence that recent Ph.D.s can use extra support in finding a job that’s right for them.”

Collecting Data to Use It

The council’s report also recommends various “conversation starters” for Ph.D. program improvement, saying that “culture change happens incrementally and requires active participation of students, faculty and employers. A good first step is understanding how your campus community communicates about career options for Ph.D.s.” Example questions for campus colleagues include, “What kind of resources and guidance does your institution offer to humanities faculty members, so that they talk to their students about the diversity of humanities Ph.D. careers?” along with “What is your institution and its humanities Ph.D. programs doing to foster partnerships with current and prospective Ph.D. employers? How effective are those strategies?”

Emily R. Miller, associate vice president for policy at AAU, said a number of institutions have responded to her own organization’s 2017 call for transparency. Echoing some of the council’s conversation starters -- and the strong implication that data collection means little if it’s not being put to use to help students -- she noted that the AAU’s Ph.D. Education Initiative is also about promoting “more student-centered doctoral education” by “making diverse Ph.D. career pathways visible, valued and viable.”

That kind of “culture shift would foster changes in institutions and departments that would make the educational environment for doctoral students more hospitable for all students, and more fruitful for their success in career pathways both within and beyond the academy,” Miller said.