You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Ithaca College Open the Books

Ithaca College previously announced plans to cut more than 100 full-time faculty positions. Now that those cuts are actually happening -- that numbers have become the names and faces of valued colleagues -- campus opposition is ramping up. Faculty, student and alumni groups are highlighting what the college stands to lose in terms of academics and soul. They’re also accusing Ithaca of failing to make a compelling case for its drastic action.

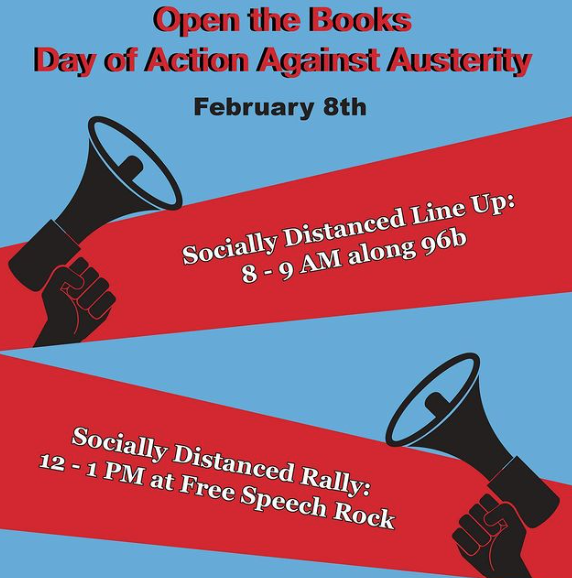

A virtual alumni town hall about the cuts last week saw 150 attendees, and the IC Alumni Against Austerity Facebook page has 1,100 members. Ithaca’s politics department has said that the termination of two longtime colleagues is a “mistake that will have a large negative logistical and curricular impact on our department and on the college.” And today the Ithaca College Open the Books Coalition -- including students and the college’s part-time faculty union -- plans a socially distanced on-campus demonstration.

Cutting the Most Vulnerable

Key to understanding this backlash is Ithaca’s somewhat unusual faculty structure, and where the cuts are concentrated. No tenure-track or tenured faculty jobs are at stake, but many departments’ non-tenure-track ranks are being wiped out.

Ithaca has part-time adjuncts, many of whom are losing their one- or two-class-per-term assignments. Ithaca also has a core teaching staff of ranked, non-tenure-track professors working on multiyear contracts. Many of these professors were recruited through national searches and -- under the premise of steady employment -- became deeply involved in curriculum design, shared governance, service work and student activities. So with many of these professors losing their jobs, as well, there’s a pervasive feeling that Ithaca is gutting its academics and its campus culture.

Sara-Maria Sorentino, an Ithaca alum who is now an assistant professor of gender and race studies at the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa, said her own faculty experience makes her all the more “shocked” that some of her former professors in politics are being laid off.

“I don’t see how Ithaca can survive this, at least not in the spirit and substance that has preserved alumni memory,” she said. The “excision of central people and programs,” among other administrative actions, “will be a wound for Ithaca for a long time to come.”

Sorentino added, “I cannot imagine many alumni wanting to donate to, or otherwise publicly support, the school under this new vision.”

In October, Ithaca said that it planned to cut its full-time faculty ranks by 130, in a COVID-19-related acceleration of a five-year plan and an attempt to bring the student-faculty ratio to 12 to one from 10 to one.

“There is no joy in this,” La Jerne T. Cornish, provost, said at the time. “It is painful and it is necessary. If Ithaca is going to thrive and continue to serve generations of students, we’ve got to address our issues right now, without delay.”

In the interim, Ithaca underwent an academic prioritization plan. Faculty members were asked to contribute to the process by providing program enrollment and other data, but the primary prioritization committee included no faculty members.

Last month, that committee recommended cutting 116 full-time positions instead of 130. Those include 86 full-time reductions, half of which are in the arts and sciences, and an additional 30 to come from decreases in faculty release time and 24 positions vacated through attrition over the next three years.

Bigger Impact

Though smaller than originally announced, the 116 number is significant, given that Ithaca’s total full-time faculty count is 547. The total number of professors immediately affected will be more than 87, as well, given that many are adjuncts who don’t teach full-time.

Some 37 professors have already self-identified as having been laid off. They include colloquium coordinators, those serving on diversity, equity and inclusion and strategic planning committees, a Model United Nations adviser, Faculty Council representatives, one involved in Jewish student life and anti-anti-Semitism initiatives, an adviser to Students for Justice in Palestine who led antiracism initiatives, and the director of nature and recreation programs.

“It’s very odd, what’s happened, and its feels like a series of missteps,” said Fae Dremock, a full-time, non-tenure-track assistant professor of environmental studies and science who was told last month that her job is disappearing. Of the college’s relatively new upper-level administrators, Dremock said, “I think they didn't realize the values and strengths and structure of the college. And I do think they’re using COVID to create change that isn’t necessarily in response to COVID, which is also a problem that many faculty are reacting to.”

Patricia Rodriquez, chair of politics, said she's seen no "justification given to substantiate these cuts to our department, in terms of program needs and demand." The prioritization committee gave faculty members "no evidence that they engaged with the data that we were asked to look at in our own analysis," she continued. Politics will be forced to suspend its popular Model UN and Model European Union programs, as well as plans for a new policy minor.

"The loss of our colleagues will affect faculty morale in the department and chip away at trust in the college administration," Rodriguez said. "The choices being made for short-term budgetary purposes will generate a spiraling long-term disaster from which the department is unlikely to recover."

Like so many other professors who have been cut or faced with reimagining program curricula in their colleagues’ absence, Dremock wondered which of her courses and initiatives will “vanish” when she’s gone. She teaches an introductory environmental humanities course required of all department majors, for instance, and another that teaches future environmental scientists how to communicate with the public online about their work, as a team of entrepreneurs.

Dremock was specifically recruited to Ithaca seven years ago for her humanities expertise, and now it’s apparently put a target on her back. That, in turn, changes the culture of the department.

“We have a lot of students who transfer in from other departments, as we’ve had a reputation for being quirky, innovative and interesting. We also really build community.”

Instead of a top-down plan that hollows out programs, Dremock said Ithaca is full of “brilliant people who really like and care about the school and its students,” who would have come together to find alternative means of saving money.

Thomas Pfaff, a tenured professor of mathematics whose own job is not in jeopardy but who is concerned about the direction of the college, linked the faculty cuts to Ithaca’s previously stated desire to shrink its target student enrollment from 6,000 to 5,000. Yet there’s been no faculty input regarding that target, he said, “nor, in my mind, has the administration justified this decision in any way.”

While higher education certainly has its “challenges,” Pfaff said, it’s “hard to understand why we need to shrink 20 percent. This is not just a lack of shared governance but a complete lack of transparency and interest in collaboration on the part of administration.” Pfaff added, “From my perspective, I’m having a hard time figuring out how given our infrastructure that the reduced student size makes sense. The generally across-the-board cuts also creates a lot of weakness in many programs across campus.”

Outstanding Questions -- Namely, ‘Why?’

Previously, Ithaca said its 2020 fall enrollment was down 15 percent, due to COVID-19.

In any case Pfaff said, the faculty layoffs “are not even close to cutting costs enough to match our reduced revenue stream” resulting from 1,000 fewer students. Ithaca has said that academic prioritization will eventually save the college up to $8 million annually, Pfaff noted, whereas tuition revenue will decrease by a “ballpark” $20 million each year, even when considering an average discount rate of 55 percent.

Ithaca says it’s currently gathering feedback on the recommendations, with a plan to submit final recommendations to the provost and president by March 1. Clashing with faculty accounts of what’s happened over the last six months, Ithaca says it’s been transparent with the campus, citing public guiding principles for the academic prioritization process and an FAQ page.

Shirley M. Collado, Ithaca’s president, said in a statement that the prioritization committee’s “deep commitment to an inclusive and holistic process resulted in a slate of draft recommendations that centers our students, demonstrates a heartfelt compassion for our faculty and staff, affirms our institutional commitment to the liberal arts and professional education, and honors and supports the important role that tenure plays in maintaining faculty excellence.”

The next step, she said, “is to hear from our faculty and campus community, and I look forward to these honest, constructive, and critical conversations about the committee's recommendations.”

Alumna Sarah Grunberg, who is now an instructional designer at Cornell University’s eCornell, said that from her perspective, Ithaca’s senior leadership team “has been rather unclear and reluctant to clarify the reasoning behind the cuts. Of course cutting folks at an institution will save the institution money, but why this many cuts at once? Why during a pandemic?” Grunberg also said it’s suspect that the cuts target contingent faculty members, who represent the only unionized faculty group at the college.

Grunberg continued, “There seems to be messaging stating that the college is both in great financial standing, and also that the college must pursue these cuts immediately.”

Without clear, convincing answers, she said, various groups are “coming together to resist this unethical firing of our friends, mentors and colleagues.”

James Miranda, a lecturer in writing and chair of Ithaca’s Service Employees International Union-affiliated part-time faculty union, said that he and his cut part-time colleagues are “pretty much done after this semester.” Many of their departments, meanwhile, “have no idea how they’re going to staff their courses in the fall.”

Echoing others on campus, Miranda said it’s unclear why these reductions aren’t furloughs instead of layoffs.

“When we say, ‘Why does this all have to be done fast?’ the answer is, ‘COVID accelerated things.’ When we ask about the budget, then, we hear that it’s not really a budget issue, but rather, ‘something we were always going to do.’ So it’s this circular logic-type argument that still ends with over 150 people losing their jobs in the midst of a pandemic.”