You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Ketut Subiyanto/Pexels.com

Numerous recent studies highlight the coronavirus pandemic's disproportionate blow to female academics’ productivity. Other studies highlight the pandemic’s toll on academics who are caregivers.

A new study of thousands of professors from Ithaka S&R, out today, highlights the particular struggles of female caregivers working in academe -- and what institutions can do to help them.

Lasting Impacts

First, a question: Why does another study on this topic matter, especially now that people are getting vaccinated and colleges are planning for a return to something like normal come fall?

The answer? Experts say that given the time-consuming nature of academic research and the relatively prolonged academic publishing cycle, female academic caregivers are likely to be feeling the professional effects of the last 12 months for a long time. And while more data are almost always better data, as far as academics are concerned, each new paper hopefully encourages institutions to develop and honor meaningful policy changes.

“Delays to planned research will inevitably delay research publications, which in turn will impact tenure and promotion prospects,” said study co-author Christine Wolff-Eisenberg, manager of research and surveys at Ithaka. So while instruction and student learning “might look relatively more normal in the fall, trends related to research productivity and employment are likely to impact women and caregiver academics for years to come.”

That’s not even counting the many women who have been laid off or left the workforce in the last year, across the economy, Wolff-Eisenberg pointed out.

As for this new study, co-author Makala Skinner, a senior analyst at Ithaka, said what sets it apart is that “we looked not just at gender or caregiver status, but at the intersectionality of the two. It’s not only that faculty who care for others have lost time and productivity, but very specifically that even when we account for caregiving status, women carry a larger burden and are impacted more substantially than men."

Wolff-Eisenberg said these disaggregated data “really add greater nuance to the national discussion.”

Jessica Calarco, an associate professor of sociology at Indiana University who is not affiliated with the Ithaka paper but has been studying the pandemic’s effects on working mothers, including some academics, said the new report “reveals that pandemic-related gender inequalities in academia aren't just a function of women's greater likelihood of having caregiving responsibilities.” Rather, she said, “these are gendered caregiving inequalities that impact women caregivers more than men caregivers.”

This means that while college policies targeted at supporting caregivers will help women, she said, “they won't necessarily be enough to address the gender inequalities created by the pandemic.” Instead, colleges and universities “will likely need to take steps to address the pandemic's disproportionate impact on women caregivers.”

On the why-does-this-matter question, Calarco weighed in, too. “This study and others like it are critical for reminding universities of the damage done by the pandemic,” she said, “and the steps that will be necessary to avoid exacerbating long-standing inequalities between men and women and especially between men and women caregivers in academia.”

The Scope of the Study

The Ithaka report is based on a survey that Wolff-Eisenberg and her co-authors fielded in the fall at a large, unnamed urban university system with two- and four-year institutions. The survey yielded 3,210 responses, for a response rate of 21 percent.

About half the sample were women, and about half the sample were caregivers of some kind. Twenty-two percent were female caregivers, and 16 percent were male caregivers.

Both women and caregiver faculty participants were much more likely to experience a variety of difficulties in their personal and professional lives during COVID-19, the study found. More women than men said it was difficult to manage their time (53 percent of women compared to 39 percent of men); to balance family, household and work responsibilities (56 percent versus 44 percent); and to manage childcare or homeschooling children (65 percent versus 55 percent).

These gender gaps tended to be smaller among faculty members in the arts and humanities than in the physical and social sciences. The gender gap for balancing family, household and work responsibilities was only four percentage points for professors in the arts and humanities, for instance, but 12 percentage points in the physical sciences and 17 percentage points in the social sciences.

This was also the case for caregivers, male and female, who were significantly more likely than noncaregivers to find difficulty with each of these activities, the study says. About half of caregivers said finding a quiet place to finish work was difficult, compared to 17 percent of noncaregivers.

Where Gender and Caregiving Intersect

Getting to the crux of the analysis, the study says that more differences emerge at the “intersection of gender and caregiving.” Female caregivers experienced difficulties with time management (63 percent) and balancing family, household and work responsibilities (75 percent) more than male caregivers did (48 percent and 61 percent, respectively). Women caregivers were also more likely than men to find remote work difficult (41 percent versus 31 percent.)

All of this “signals that there is an imbalance in the amount of labor that caregivers are engaged in by gender,” wrote Wolff-Eisenberg, Skinner and co-author Nicole Betancourt, also of Ithaka.

Perhaps surprisingly, given the rapid jump to remote instruction, 86 percent of all respondents reported being at least somewhat prepared to teach remotely last semester, with no significant difference among subgroups. They felt even more confident about being prepared to teach remotely in the future.

“This outcome is one that we have seen consistently over the last several months, with faculty generally indicating that they feel more and more prepared to teach remotely,” the authors noted.

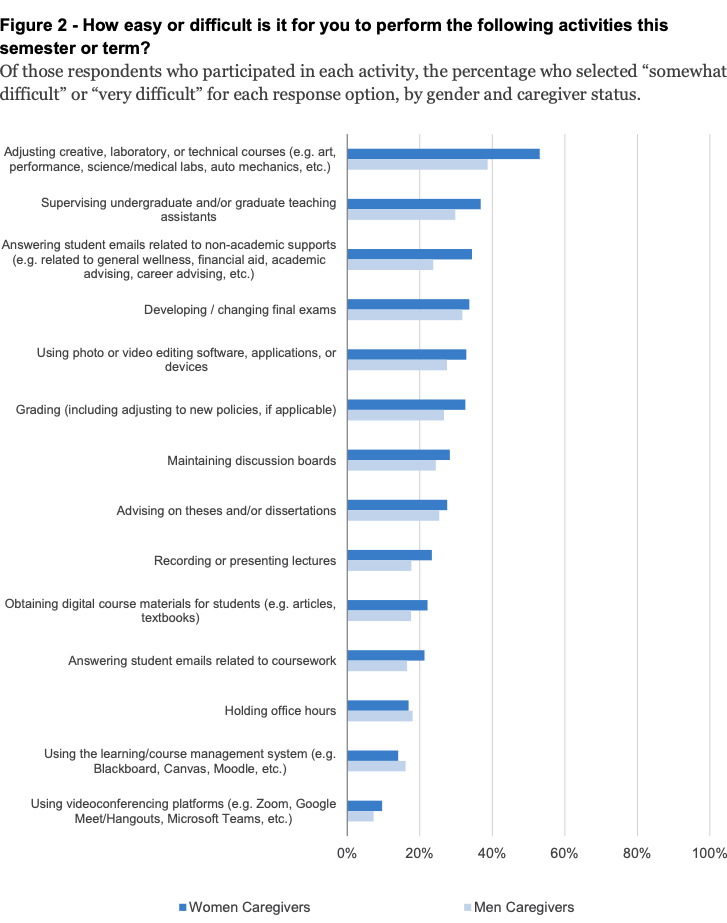

Both women and caregivers did experience more difficulty related to teaching than men and noncaregivers, however. Women and caregivers found it harder to respond to student emails that weren’t specifically about academics, for instance. This was true across fields. Caregivers also said it was harder to respond to student emails even about coursework.

“This further strengthens the argument that women and caregivers are facing an imbalance in the amount of labor that they are engaged in within their personal and professional lives, which could be contributing to the difficulties that they experienced with performing various activities related to teaching during the fall 2020 semester,” the report says.

On research, 57 percent of respondents said they worked much less on research than planned during the fall semester. Breaking that down by gender, however, a big gap emerged: 50 percent of men compared to 62 percent of women. This was consistent across disciplines.

“Even when taking into account whether faculty have substantial care-giving responsibilities for other people in their household, a gender gap remained, with 66 percent of women caregivers reporting that they conducted research much less than planned compared with 56 percent of men caregivers,” the report says.

Research Woes

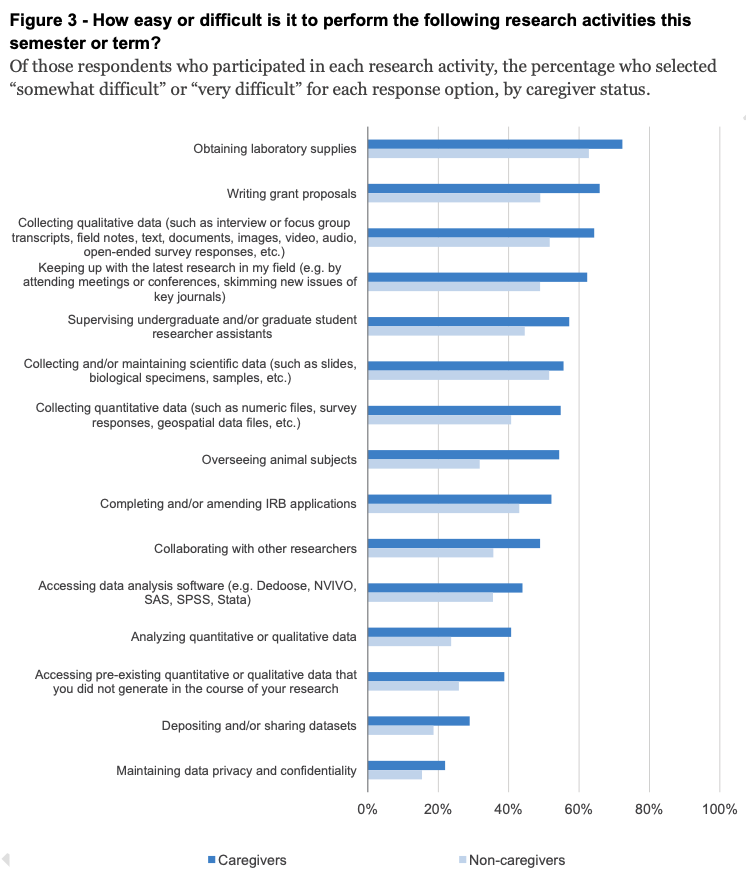

As for which research tasks were most challenging, 24 percent of faculty members without caregiving responsibilities found it difficult to analyze quantitative or qualitative data, compared to 41 percent of caregivers. Writing grant proposals was a particular challenge for caregivers, as well. This was across disciplines.

Between men and women, women were more likely to say it was hard to focus on writing grant proposals. This, the authors say, “is particularly alarming given the long-term impact this may have for career advancement in the future.”

Perhaps surprisingly, given that much physical science research can only be done in a lab, the largest gaps between men and women with respect to research were in the arts and humanities. There was a 19-percentage-point gap among humanists for writing grant proposals, for instance. The social sciences had the smallest average gap in research difficulty: on collaborating with other researchers, arts and humanities professors had a 13-percentage-point gender gap compared with only a three-percentage-point gender gap in the social sciences.

Gender differences emerged among caregivers here, too, with 70 percent of female caregivers finding it difficult to keep up with the latest research in their field compared to 54 percent of male caregivers.

“We also saw a decrease in publications and other research outputs among caregivers” as well as women, the study says, addressing research productivity. Interestingly, regarding writing papers and draft manuscripts, the largest gap between women and men -- 14 percentage points -- was among social scientists. Among physical scientists, the gap was six percentage points. It was three percentage points among arts and humanities professors. Trends among caregivers and noncaregivers regarding producing data, images and media were similar.

In all, the paper says, “Women faculty with caregiving responsibilities bore the brunt of this lost research output.”

Implications, Solutions

Skinner this week said that the significance of this lost time for female caregivers can’t be overstated, as it will “follow faculty for several years, and for some, will even change the trajectory of their career rather than delay it.”

While solutions aren’t the focus of the paper, and “there are no easy answers,” Wolff-Eisenberg and her colleagues included some ways that institutions have begun to mitigate these gender gaps in research and better support professors with caregiving responsibilities.

These include temporarily reducing or suspending research publication requirements in the short term. Other ideas are prioritizing, simplifying and reducing faculty tasks, along with providing faculty members flexibility where possible. Recalling the University of Massachusetts at Amherst’s decision to automatically delay tenure review for everyone by one year, the report says this “does not require faculty to request the deferment, an important detail that removed the burden of opting-in or applying.” Those who wanted to be reviewed on schedule could opt in.

“Most importantly,” the authors wrote, “it is crucial that institutions listen to the women and caregivers they employ. Needs may vary from school to school and from person to person; by listening carefully to what faculty members share, institutions may avoid well-intentioned supports that in reality exacerbate rather than alleviate disparities.”

Non-tenure-track faculty members have some different needs than tenure-track and tenured faculty members, the report says, and this in turn has implications for diversity and equity, and Black, Native American and Latinx women are most concentrated off the tenure track.

It’s “also important to bear in mind that while the pandemic highlighted and deepened disparities between faculty, it did not create them,” the report says. “Schools will need to reflect on long-standing institutional practices related to hiring and promotion in order to adequately address issues of equity.”

Parallel Insights

To this point, Stanford University’s Faculty Women’s Forum recently shared findings from a COVID-19-era faculty satisfaction survey. The pandemic caused “a lot more stress” for 57 percent of all respondents, according to university report, more so for women, tenure-track professors, those at the lower end of the salary scale and those caring for children. Thirty-six percent of all respondents said they were dissatisfied with Stanford’s pandemic response, with tenure-track professors the most dissatisfied of all. This has implications for retention: 27 percent of respondents making between $100,000 and $150,000 annually said they are more likely to leave Stanford post-COVID.

Forty-five percent of the Stanford respondents said they were spending at least four more hours per day as a primary caregiver now compared to before the pandemic. Here, like in the Ithaka survey, gender differences emerged: whereas 50 percent of women said they were spending at least four more hours on caregiving now, 33 percent of men said the same. Women also reported spending more time educating their children at home. Associate and assistant professors were the most stressed in these ways.

Unsurprisingly, these findings correlate with lost research time. Some 75 percent of the Stanford respondents said they were spending less time on research, and 85 percent of those professors said they expected to decline, cancel or postpone a publishing or research commitment due to COVID-19. Many faculty members also reported spending more time dealing with online teaching, service and advising and mentoring students struggling with the pandemic.

Anne Joseph O’Connell, Adelbert H. Sweet Professor of Law and a member of the forum’s steering committee, said that while caregiving responsibilities have “generally jumped for all who have children, they have increased more for women than for men -- resulting in detrimental short- and long-term consequences.”

Eve Higginbotham, vice dean of inclusion and diversity and a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania and chair of a major National Academy of Sciences report on women in the academic sciences during COVID-19, said the scope of the new survey -- in number of respondents and their disciplines -- offers “more observations for us to build on as an academic community.”

It’s notable, for instance, that the experiences of male and female caregivers seem to vary by discipline, and that female caregivers were more likely than male caregivers to have trouble controlling their time, “emphasizing the gendered roles of caregiving,” Higginbotham said. The gender gaps in successfully finding time to do research and write grant proposals, in particular, doesn’t “bode well” for career trajectories.

What the survey has in common with the National Academy of Sciences’ report, Higginbotham said, “is the need for institutional acknowledgment and response to these stressors -- and the unintended consequences that some policies have on the academic vitality of faculty that may differ between men and women.” It doesn’t have report’s scope of suggested research, though, she said, and it doesn’t “tee up the impact of faculty from marginalized communities and the additional stressors these faculty face based on their intersectionality and confluence of additional stressors such as structural racism.”

During a recent Women’s Faculty Forum presentation at Stanford, Provost Persis Drell said the university has tried to alleviate some faculty stress this year by offering teaching and administrative relief during and after the pandemic, various kinds of financial assistance, tenure-clock extensions, and technology support.

Even so, Drell said, “The pandemic has interrupted careers. It has placed unprecedented stress on faculty and dragged on much longer than any of us had originally anticipated.”

O’Connell said Tuesday that Stanford had indeed adopted some “helpful” measures. But academe can’t “lose sight of the long-term consequences.” The Stanford survey shows a “stunning gap on grant writing,” and “fewer grants in the immediate future mean less research in the years to come,” she added, echoing others.

Universities should work to ensure that tenure-clock extensions and other measures designed to address the effects of COVID-19 don't "end up exacerbating inequalities," O'Connell said, noting that some research shows parental leave policies benefit men more than women, for instance.

While Stanford’s focus is “rightly on those who are pretenure,” O’Connell also said, “the gendered effects of the pandemic, including increased student needs that fall disproportionately on women and faculty of color, will also produce gaps in later career stages.”